Community Time Capsule: Russian American

Prima and Evsey Reitynbarg's Family Photos and Portraits

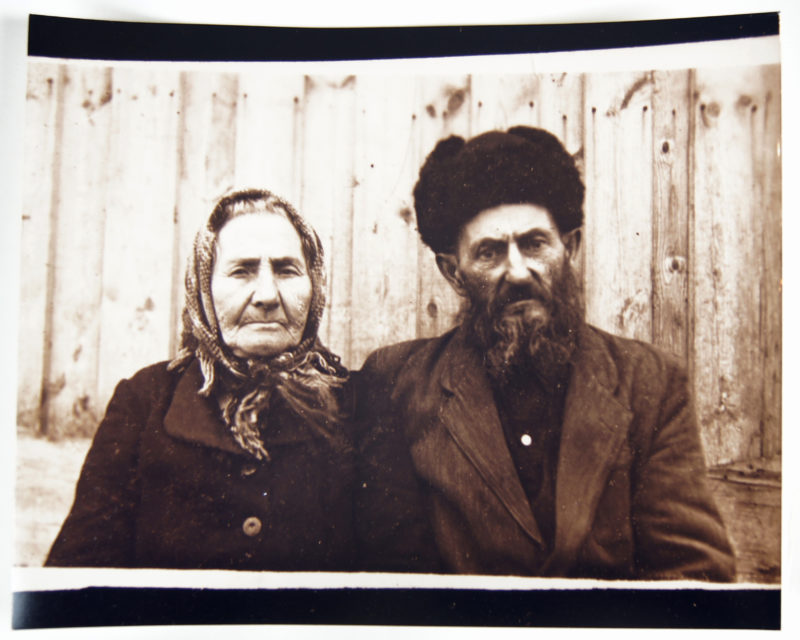

Evsey’s grandparents, 1951. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Evsey’s Grandparents, 1951

“My husband, Evsey’s grandfather was named Zalman Yitzakovich Mnuskin. His grandmother was Seina. She was born in 1910, he in 1904. They lived in Rechitsa, a village in Belarus. He was a very pious Jew. He could read and write in Yiddish and Hebrew and also he fluently read and wrote in Russian. Zalman was a very deep believer. There was a prayer room in his home. He observed all the Jewish holidays. To earn a living, he worked as a joiner or cabinet maker. Evsey remembers that Zalman went crazy for the idea of the perpetual motion engine. His grandmother, Seina, was illiterate, but on the other hand she was a great housekeeper. Every day she cooked kosher food. Zalman successfully taught Evsey his craft—metalworking, lock-smithing, cabinet-making. What’s more, he taught his grandson to be honest and fair and to help those less fortunate.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Evsey's Father. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Evsey's Father

“This is the father of Evsey, Solomon Mnuskin. In this picture you can see him with many medals. He earned them during the war (1941-45). He passed through all the war years as an ordinary soldier. He was wounded.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Red Army Medals. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Red Army Medals

“He got several medals for the conquest of Vienna, Budapest, for victory over Japan, victory over Germany, victory in the Second World War, and the last medal for courage. When he was at war, his family was evacuated to Isakli. They lived there in poverty and starvation until the war finished. All through the war Evsey helped his mother to survive and raise his younger siblings, although he himself was only ten years old when the war started. Then, they returned to their home in Belarus, to Rechitsa.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Papa. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Papa by Eduard Yanov

“The artist who made this painting is the Russian painter Eduard Yanov. It is made from a photograph of my father.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Mama. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Mama by Eduard Yanov

“The artist who made this painting is the Russian painter Eduard Yanov. It is made from a photograph of my mother.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Prima and Evsey's American Family. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Prima and Evsey’s American Family

This photograph of Prima and Evsey’s entire American family was taken in 2012, in Pittsburgh. Pa

“The whole family Mnuskin/Reitynbarg, can not gather very often. The oldest son lives with his wife and three children in Pittsburgh. The youngest son, a father of two, lives in Minneapolis. Our family looks like a dynasty of physicians. There are now seven doctors in three generations. Recently my oldest granddaughter, Alexandra, Sandy, became a doctor.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Prima’s Parents and the Malakhovka Colony. Group Portrait—Soviet Psychologists. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Prima’s Parents and the Malakhovka Colony

“My parents, David and Nechama, worked in the 1920s until the beginning of the 1930s in an orphanage for Jewish children and teenagers. This colony was established not far from Moscow in the suburb of Malakhovka, about thirty kilometers from Moscow. The civil war in Russia continued for almost four years, from 1918 until 1922. And during this time, many children—Russian and Jewish—were left without parents. They lived in the streets, in basements, and abandoned buildings, in sheds and other very bad places not suitable for habitation. In order to survive, they robbed, cheated and formed criminal gangs. The Soviet government tried, not a little, to help these orphans who were a consequence of the war. The Jewish colony of Malakhovka was one of the first such places in the Soviet Union. It was a colony with children’s auto-authority. The children worked themselves and did a lot. They grew vegetables, potatoes, chopped wood, heated ovens, cooked their food, cleaned their houses and took care of all aspects of housekeeping. At the same time, they studied in school and all of them became very decent people. They kept their brotherhood all of their lives. And in the 1960s and 70s, when my father, David, was still alive, I attended with him their very warm and cordial meetings.” —Prima Reitynbarg

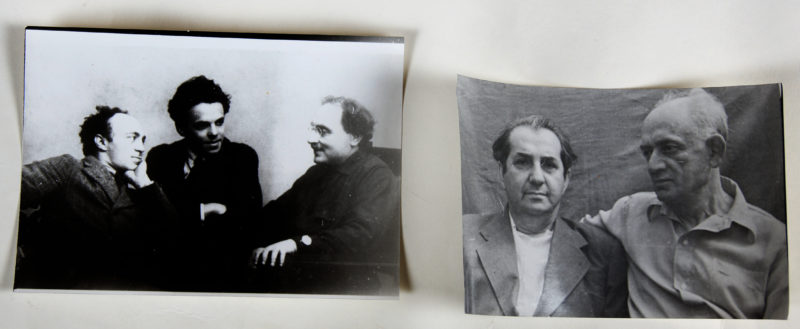

David Reitynbarg with Figures of Jewish Culture. Meyerhold and Company. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

David Reitynbarg with Figures of Jewish Culture

Reitynbarg and the poet Samuel Galkin, and Solomon Michoels, Zuskin and Dobrushin. The second photo has the caption “Solomon Micholes was killed in 1948, Zuskin and Dobrushin in 1953” Date of photo unknown.

“This is my father, David, with the poet Samuel Galkin: David was very close to many figures of Jewish culture. It is not possible to enumerate all of them, but first of all, Samuel Galkin, the outstanding Jewish poet.”

“Solomon Michoels (1898-1948) was one of the main founders of the famous Moscow Jewish Theater (1920), its producer and star actor. He was also a prominent public figure. David adored the Moscow Jewish Theater, it’s genius actors, Michoels, Zuskin and others, and kept up acquaintances with Jewish writers who worked for the theater: Perets-Markish, Yitzik Pfeffer, Dobrushin. Although I did not speak or understand the Yiddish language, my father brought me to performances and I understood the content because of the high level of theatrical skill.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Cousins, 1940s. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Cousins, 1940s

“This is a photograph of me (top left) with my aunt Frieda (bottom right) and cousins, Lena (top right), Ina (below left), and Galina (top middle.) (Frieda was the mother of Galina and Lena, Ina was the daughter of Maria.) The photograph was taken in the late 1950s or early ‘60s. All of us are related on my mother’s side. My mother, Nechama Geller, died in 1944, during the war. She had four sisters and one brother. The oldest sister, Rachel, emigrated to America in the 1920s, and lived a fortunate life. The three others, Lea, Frieda and Manya (Maria) were victims of Stalin’s regime in the 1930s. Lea was shot, Frieda and Manya were jailed with their husbands for about twenty years, accused of being counter-revolutionaries (along with ten million others.) Lea and Frieda were followers of Trotsky. Manya was not political, but she worked in the ministry of foreign affairs. Lena, Ina, and Galina became, in fact, orphans, but survived thanks to close relatives. Nechama’s only brother, Abel; his wife, Kret; and their daughter, Rachel were killed in the beginning of the War in the Vilna Ghetto.” —Prima Reitynbarg

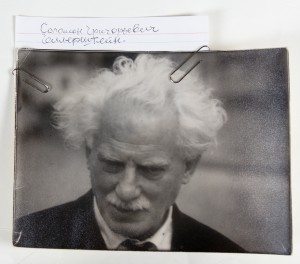

Samuel Gellerstein and the Psychotekniks. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Samuel Gellerstein and the Psychotekniks

“I grew up in the company of my father’s colleagues—a group of psychologists called psychotekniks. My ear absorbed new words, ‘psychology of work,’ ‘professiogram,’ ‘psychogram.’ My father, David Reitynbarg, Solomon Gellerstein, Isaac Naftulevich Spielrein, Vladimir Kogan, Julius Spiegel, Alexander Abramovich Neifakh—these were the psychotekniks. Their field was the psychology of labor—how a person chooses a profession—the most important task. It also empirically described the characteristics of a range of professions. Among other magic words that I heard, ‘aptitude’ was especially exhilarating because it concerned not the assessment of someone else, but of me. For example, the profession of pilot requires the speed of response, of reaction; the work of circus performer, agility of movement. Is there anything that I would be good at? Is there something worthwhile in me? My father and his friends didn’t tell me what I wanted to hear—praise—they only teased me.” —Prima Reitynbarg

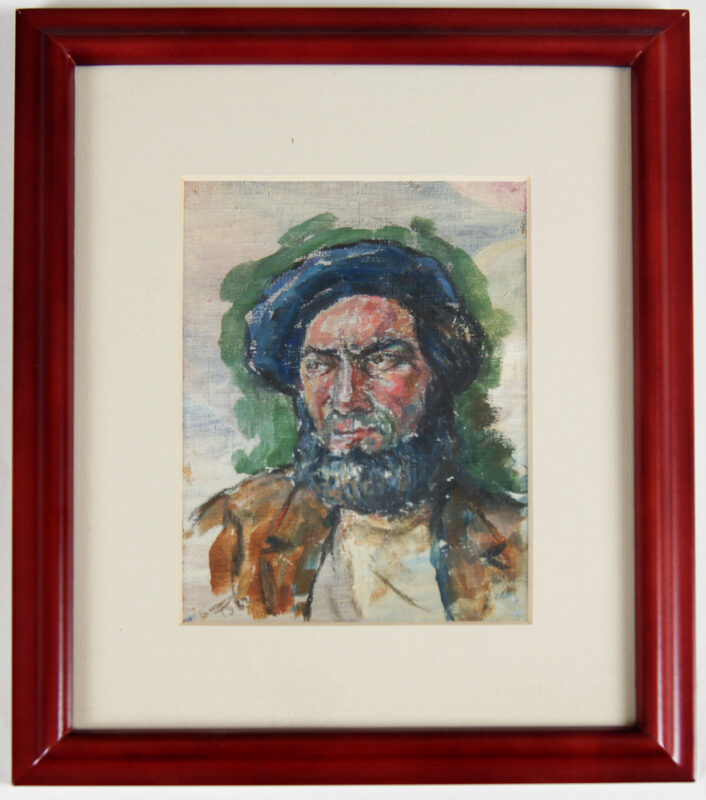

Evsey's Portrait. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Evsey’s Portrait, 1972

“It is a very picturesque portrait. The portrait is painted with a little touch of humor, or even the grotesque. Evsey looks like a menacing oriental ruler—it looks funny. A real artist who worked with Evsey on construction painted the portrait. It was done in 1972. Evsey was a builder, he operated a crane. He built bridges and buildings and all of Moscow. The artist who made this portrait could not earn enough money to live on making pictures, and was compelled to give up his art. As a construction worker he earned real money. I was very glad to get this piece of art, although Evsey did not like it very much.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Irina Peris’s Family Photos

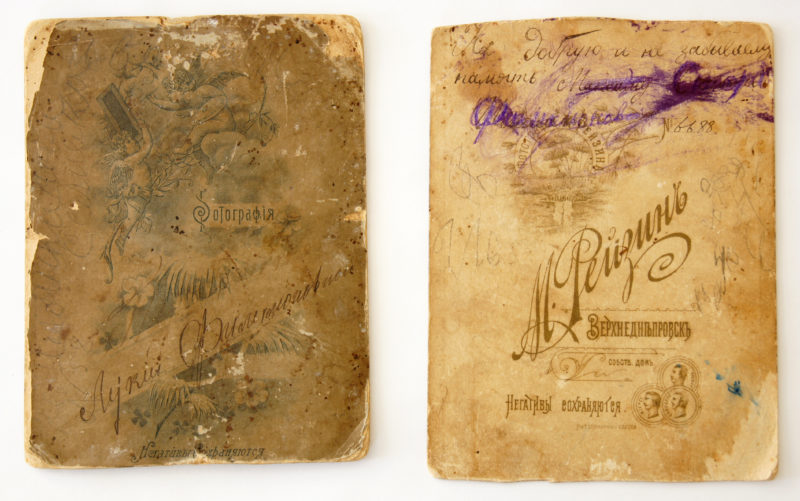

Peris's Great-grandparents, Front. Collection of Irina Peris

Irina Peris’s Great-Grandparents

“These are photographs of my great-grandmother and her husband, which would make him my great-grandfather, when they were young and engaged. I grew up with this great grandmother. Her name was Lukeria Filimonovna and she was from a strong family of Ukrainian peasants. I mean they were large and strong and there were a lot of them. She was an important figure in my family, and she was a very big presence in my childhood. Her marriage with this person did not last, even though she had three children with him. She had a life full of hardships. She ended up in the crucible of history (she lived through the Russian Civil War and Revolution) and her family was pretty much destroyed by it. She struggled all her life and towards the end of it became a truly powerful and beautiful person. I remember her as an old lady to be much more beautiful than she is in this picture as a young girl.” —Irina Peris

Peris's Great-grandparents. Collection of Irina Peris

Reverse sides of photos

This is a view of the reverse sides of the photo backings. There are writings and designs that have faded with age.

Ksenia Gushchina’s Family Photos

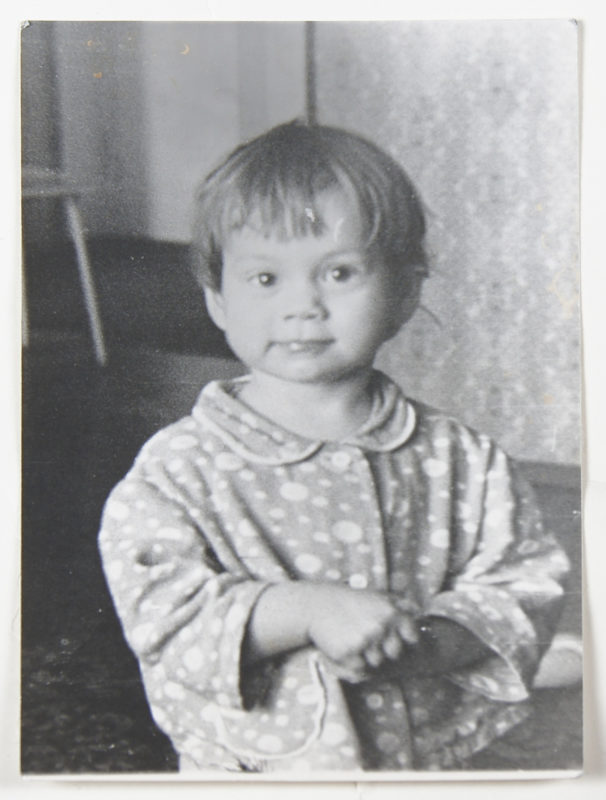

Ksenia’s Baby Picture. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Ksenia’s Gushchina’s Baby Picture

“I think my parents took this picture after I found a bag of flour and I opened it and got it everywhere. I had this happy face like ‘Ah, I did a good job!’ My parents were shocked—it was not easy to clean up. It was not a small bag of flour, you know, at the time, it was a big bag. The picture was probably taken in 1989 in Kazan, the city where I was born and raised. My parents and my whole family is still in Kazan, in Tatarstan. It’s an ancient city and very economically developed, historic, with beautiful architecture. It’s often called the third capital of Russia. The interesting thing about it is that there are two different cultures, Muslims and Christians. We don’t fight. We have a mosque and a church next to each other down town, and we have our own kremlin [parliament building]. I was one of the few in my year who took Tatar lessons. My teacher was actually Russian but she taught Tatar—that was unusual. She was a really good teacher and I really liked the language and I was the only one who took Tatar as an elective and sat for the highest-level Tatar exam. I still understand it. I actually have some Tatar friends in Pittsburgh.” —Ksenia Gushchina

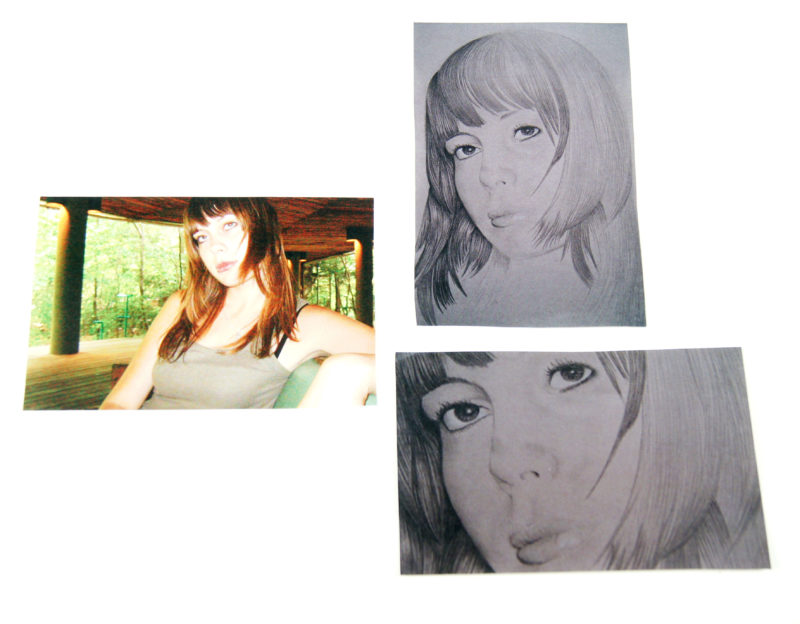

Ksenia’s portrait. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Ksenia’s Portrait

“This picture was taken at Fallingwater in 2006. That’s the first year I came to the US. [My husband] Mark took me there because he thought it was a nice place to show me. I was impressed by the architecture. I’ve never seen anything like it anywhere else. Then I went back to Russia and Mark sent me this drawing that he did from the photograph. He mailed it with two rings in the envelope—flea market rings, worth nothing. It took two months to arrive—because he put a high value on the customs slip—he ended up paying a lot of money. I was so anxious to get it, and then when I got it, I opened it and see this black frame. In Russia, black means death. So it was really weird to see my picture in a black frame! My parents were also shocked—we bought spray paint to change the color of the frame, but we never did it. I talked to Mark and he explained that since it’s in pencil he thought it would look good in a black frame. The original is still at my parent’s house, in the black frame. Also, with flowers, he would send me an even number of flowers—in Russia, it has to be an odd number, we only put an even number on a grave.” —Ksenia Gushchina

Gushchina family. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Gushchina Family Portraits

“My family never smiles in pictures—this group picture is unusual. I got braces when I moved to the states and when I got them off I started to smile. My brother also thinks he doesn’t look good with a smile in pictures. This was my mom’s birthday in 2009, the year that I got Rossiya the cat and came back to Russia. I think my mother was about twenty in the black and white picture, probably around 1977. Natasha and Lydia—Lida is my mother’s nickname. It seems weird to me now to see pictures of parties and celebrations of my family in Russia where nobody is smiling. I get pictures of my friends and they’re smiling, so maybe it’s just my family.” —Ksenia Gushchina

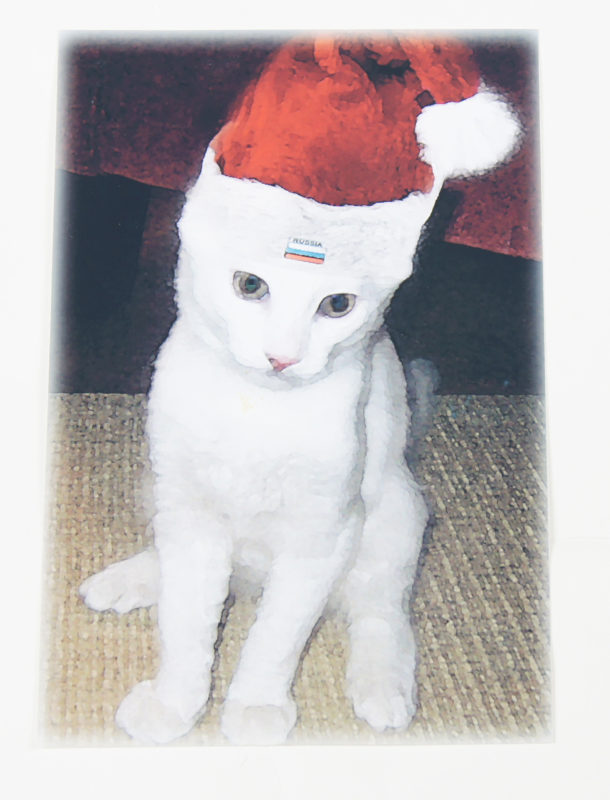

Rossiya the Cat. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Rossiya the Cat

“He was a Christmas present in 2009. I probably called him Rossiya (which means Russia in Russian) because I was going back to Russia soon and I was excited, and maybe because he’s white. I had been in the States since 2007. It was probably my second time back. He was a really weird looking cat, he had a really really long tail. Now he looks proportional.” —Ksenia Gushchina

Food

Homemade Apple Pirog. Collection of Irina Peris

Homemade Apple Pirog

“This is my favorite childhood treat. This is the open apple pie done with a yeast dough. I used to love coming home on Saturday from school (we had a six-day school week) and I would always be so happy to smell a baking pie. As an adult I came to appreciate it even more because I understand that compared to other desserts this is not quite as sweet.” —Irina Peris

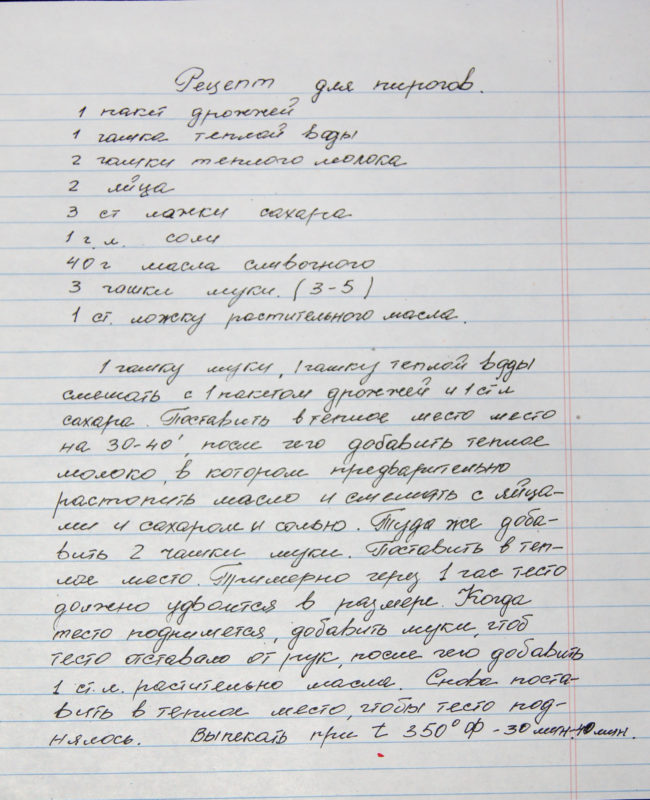

Apple Pirog Recipe. Collection of Irina Peris

Apple Pirog Recipe in Russian

Download a translated version of Irina Peris’s Apple Pirog recipe.

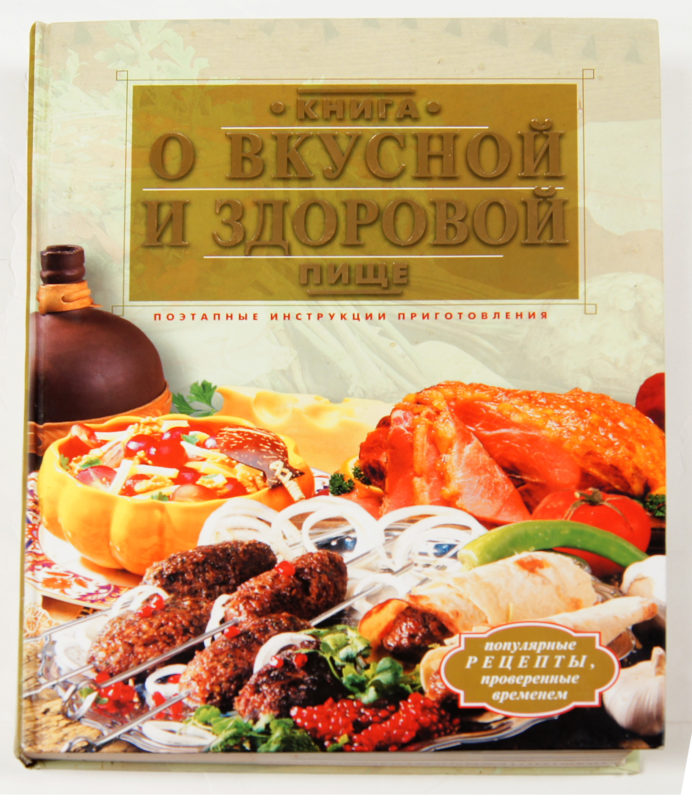

Ksenia Gushchina’s Cookbook. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

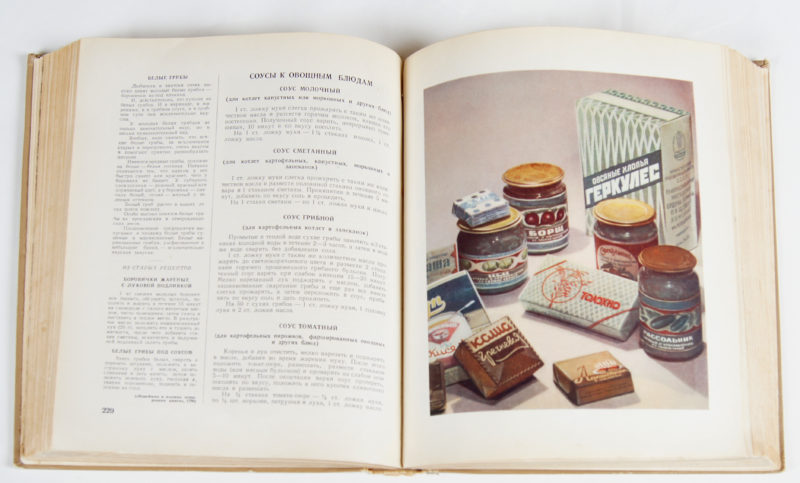

Ksenia Gushchina’s Russian Cookbook

“My mom gave me this book when I was moving to the US because I didn’t really know how to cook, and actually I still don’t know. Everything I make is boiled or baked—simple ingredients. We didn’t have this book when I was growing up. I might have made a couple of salads out of it. Russian salads all have mayonnaise in them and never lettuce.” —Ksenia Gushchina

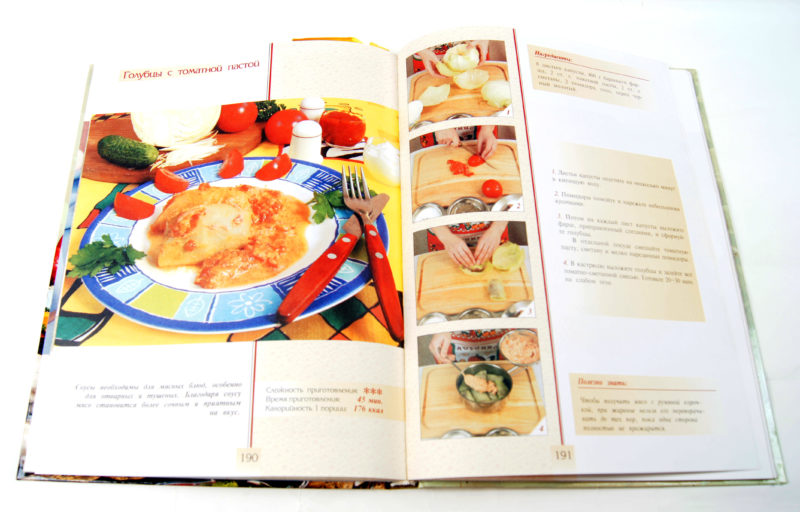

Russian Cookbook: Cabbage Recipe. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Russian Cookbook: Cabbage Recipe

“My mom is actually a good cook, she can make good golubtsi [stuffed cabbage] and I tried too from this book—mine were ok. But generally anything that takes more than ten minutes I don’t cook. These Russian salads, winter salad, Olivier salad, they’re too much work. You have to boil all the vegetables then cut them up. Russian food takes too long to cook.” —Ksenia Gushchina

German Box with Suhariki. Open View. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

German Box with Suhariki. Open View

This souvenir tin from Germany once held cookies but now holds Suhariki, which is Russian for crackers or little toasts.

“For several years in the early 2000s my husband and I lived in Shadyside. One day we made the acquaintance of a new neighbor. It was a young man from Germany who had come to Pittsburgh for a limited time, about three years, for business. Ralph was very amiable and helpful to me, and gave me endless assistance dealing with my computer. In our turn, we often invited Ralph for dinner or lunch. Our relationship developed very well and once I dared directly to ask him about his attitude and opinion related to the Holocaust and the Second World War — in Russia this war is called the Great Patriotic War (1941-45). I was afraid to find out that Ralph was a latent or concealed anti-Semite, but my neighbor answered sincerely and frankly that his generation was not responsible for what had been done to the Jews. His father had been at war against the Russians, but Ralph had no connection to all of those events. I was satisfied. One day, Ralph said that he was going back home to Germany. In gratitude for his help and our friendship, I gave him a valuable gift. In his turn, he sent from Germany a very beautiful box with cookies—a souvenir forever.” —Prima Reitynbarg

German Box with Suhariki. Closed View. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

German Box with Suhariki. Closed View

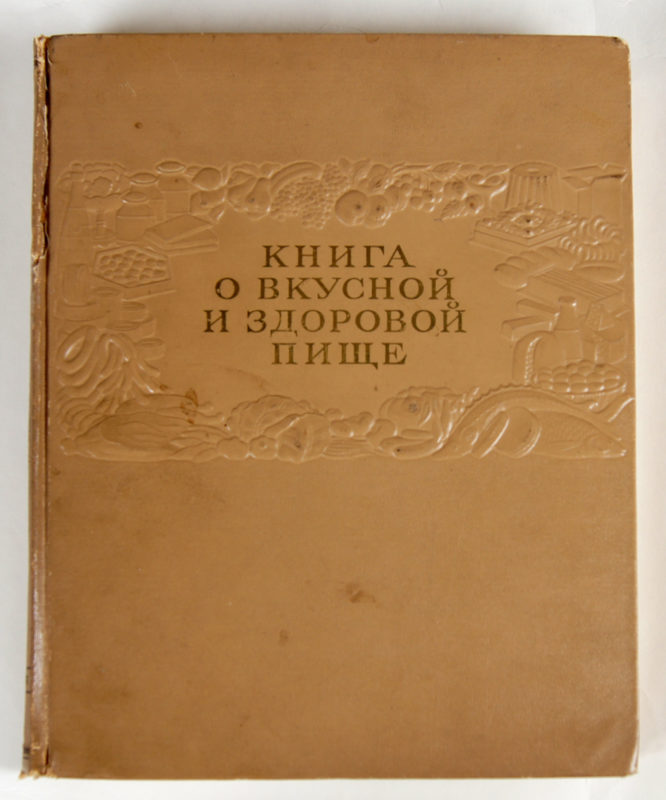

The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food. Front Cover. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Russian Cookbook: The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food

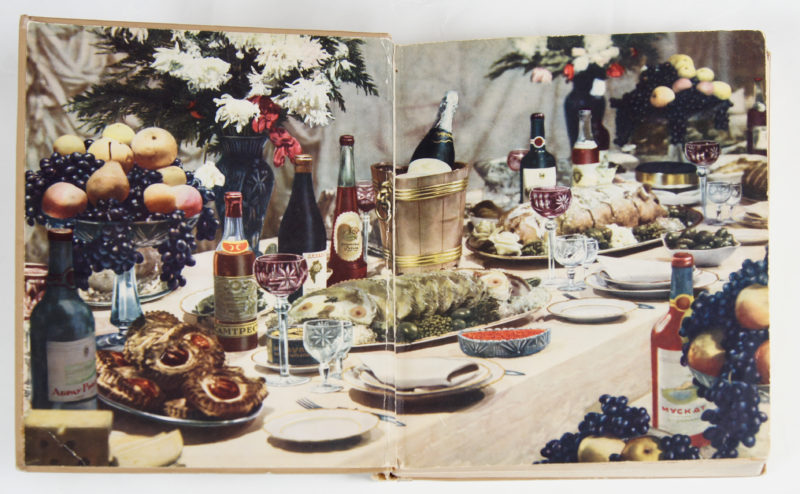

“Do you have any cookbooks? Your mother has one for sure. You can find hundreds of them in bookstores. In the Soviet Union, the first cookbook appeared in 1952. The war (1941-45) finished just several years before and starvation was still fresh in everybody’s mind. Not long before, rationing had been abolished, and people at last could eat their fill. The picture of a gala table caused tears of ecstasy. The idea of abundance seemed a miracle for Russians.” —Prima Reitynbarg

The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food. Open View. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Russian Cookbook: The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food

The cookbook opens to a depiction of a realistic spread of fine Russian food and beverages.

The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food. Open View. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Russian Cookbook: The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food

This view of the cookbook is open to a page with instructions in Russian on the left page, and an image of boxed and jarred food on the right page.

Kvashenaya Kapusta (Sauerkraut). Collection of Irina Peris

Kvashenaya Kapusta (Sauerkraut)

“This is the staple of our winter diet. It used to be a big whole-family project, when we would have to cut many, many heads of cabbage and put them in a big enamel pot and a big rock would be placed on top— I was kind of fascinated by this process. Now my mother uses a much smaller and not as impressive contraption. They cut just one head of the cabbage and put it into a big ceramic bowl and as a weight they use a jar with water. My great grandmother was the leader of the project when I was a child. We usually cut some carrot in, and rubbed it all with salt—there is no vinegar involved, it’s just a fermentation process.” —Irina Peris

Art

Railroad Spike Sculpture. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Railroad Spike Sculpture

“My former student of Russian gave this to me, he got it at the Three Rivers Arts Festival. He was just walking around, thinking of me, and got it—he came to the competition where I wore the blue dress. I have it in my apartment. It’s made of railroad spikes.” —Ksenia Gushchina

Tsar Bell. Collection of Irina Peris

Tsar Bell in the Kremlin. Moscow, Russia

“This is an image of the Tsar Bell in the Kremlin, Moscow, Russia, in the beginning of the twentieth century. The photograph was taken by an American photographer who had been traveling through Europe. The print was given to me as a goodbye gift from my first American place of employment, which was in the archives of the American Heritage Center in Laramie, Wyoming. I had not worked there for a full year as an archive specialist, and was very touched that my colleagues found an image that was relevant to my Russian background and went to the trouble of making a print and framing it for me.”—Irina Peris

Stained Glass Window. Collection of Irina Peris

Stained Glass Window

“This is the stained glass window that we made to fill an open space in the house where we presently live. It’s set into an internal wall, but it catches the light from a real window. It was made at the stained glass studio on Pittsburgh’s south side. We commissioned it; we tried to create something that would match the style of the house. We bought this particular house because it had enough historical detail to be interesting. With the window, we wanted to match the stylistics of the house.” —Irina Peris

Clothing and Apparel

2013 Steel City Classic Dance Competition Dress. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Ksenia Gushchina’s 2013 Dress for the Steel City Classic Dance Competition

“I bought this dress for an amateur competition in 2013, the Steel City Classic. I wore it for standard dances like tango and foxtrot. There were not that many people in our division, so we did win. We did well for our first competition.” —Ksenia Gushchina

2013 Steel City Classic Dance Competition Dress. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Ksenia Gushchina’s 2013 Dress (back) for the Steel City Classic Dance Competition

“I didn’t want to spend much money on the dress, but my teacher told me that someone was selling this dress—we had to change it a little bit because it had feathers on the bottom. It looked old fashioned with the feathers. I had to get a fake tan and get my hair done and makeup. I’ll probably wear it to my next competition.” —Ksenia Gushchina

2013 Steel City Classic Dance Competition Dress. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Ksenia Gushchina’s 2013 Dress (torso) for the Steel City Classic Dance Competition

“I feel like America gave me freedom to do whatever I want and I always wanted to dance. In Russia I was discouraged from dancing. There, teachers or instructors really tell you what to do, they feel their authority.” —Ksenia Gushchina

2013 Shoes for the Steel City Classic Dance Competition. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Ksenia Gushchina’s 2013 Shoes for the Steel City Classic Dance Competition

Third Generation Skirt. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Third Generation Skirt

“The alteration for my skirt was the third life of this piece of cloth. It is made of good fabric. Originally, my father, David, wore this suit, then when my older son, Dima, became a teenager, his grandfather gave him the suit for alteration. I inherited Dima’s suit when he grew up. I used it to make a skirt. Those multiple alterations were common in our life.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Records, News, and Events

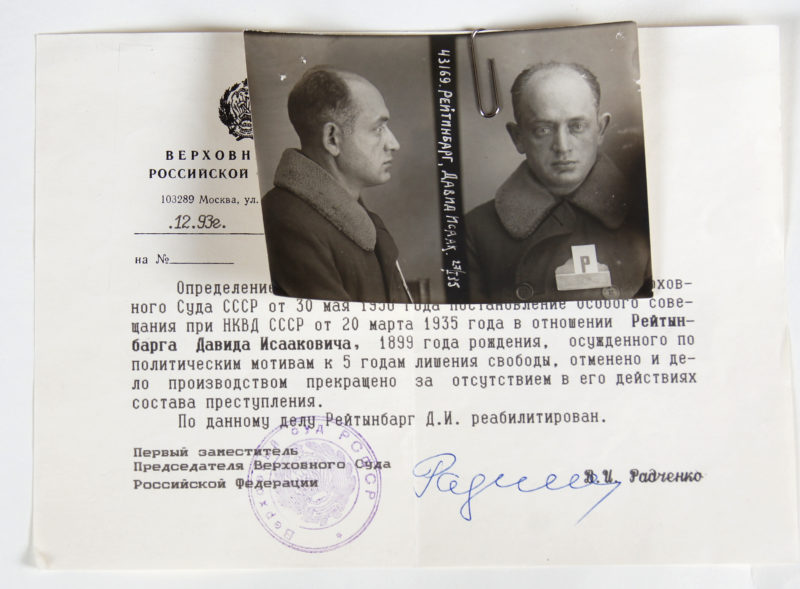

Prima Reitynbarg's Father. Gulag Mugshot with Certificate of Political Rehabilitation. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Gulag Mugshot with Certificate of Political Rehabilitation

This is a Gulag mugshot of Prima Reitynbarg’s father along with a “Certificate of Political Rehabilitation” typed in Russian. The certificate bears an official signature and stamp.

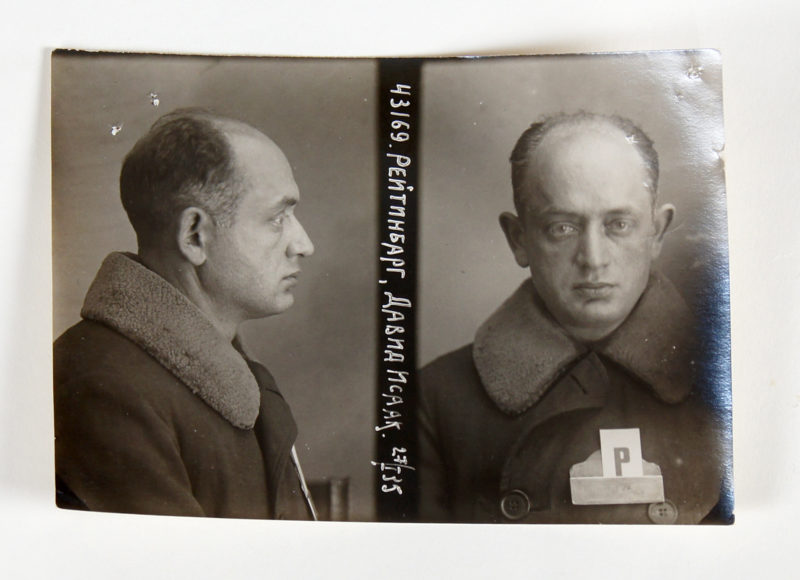

Prima Reitynbarg's Father. Gulag Mugshot. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Gulag Mugshot

A Gulag refers to a forced-labor camp in the Soviet Union.

American and Russian Passports. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

American and Russian Passports

“I’m very excited to be a US citizen, but I don’t want to give up my Russian passport because my Nationality is Russian. I haven’t traveled to Russia yet with these documents. I hear they’ve made it more complicated—I think I have to register my American passport in Russia. I might need to pay taxes to the Russian government now, I’m not 100% sure…. I was with my friends and they are saying that you need to register if you’re an American citizen and that it’s tax-related. I have a lot of friends who have dual citizenship and they’ve never had any issues but I don’t know what this year’s going to bring.” —Ksenia Gushchina

Ksenia’s passports. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Ksenia Gushchina's Passports

“For me having an American passport is great because I want to live in this country but another benefit is that I can travel without a visa—with a Russian passport I would need a Schengen visa* to get to Europe.” —Ksenia Gushchina

* “Schengen” refers to a cluster of 26 European countries which you can enter if your passport requires a visa to enter any one of them. Different countries sometimes require citizens of other countries to have a visa (official permission) to enter, and sometimes not. For example, Americans can enter the ‘Schengen’ countries without a visa—but we cannot enter Russia. As of 2014, Russian citizens with dual nationality (like Ksenia) are required to register with the Russian Federal Migration Service or face a fine of $5000 or 400 hours of community service.

Collectibles

Wartime Dishes. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Wartime Dishes

“From 1949-52 I worked as an epidemiologist in Turkmenistan, Central Asia, in the town Chardzhou. Once I was invited by my supervisor to a ‘sale,’ of course this word was unknown in Central Asia at those times. When I found the address I saw a heap of wonderful dishes lying right on the ground. They were sold for a red cent. I bought only a few of them because at that time I didn’t have a real home of my own and maybe I wasn’t able to evaluate their value. But I kept all of them for many years, and now they decorate my table from time to time.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Wartime Dishes. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Wartime Dishes (close-up)

The backside of this dish bears a green and gold maker’s logo with the words “Made in Occupied Japan” inscribed on it.

“Where did the Japanese dishes come from? Probably they came from Japan, to the Soviet Union, as war indemnity, with other war indemnities. The Soviet Union was the winner in World War II, but Japan was the loser.” —Prima Reitynbarg

Wartime Dishes. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Wartime Dishes (close-up)

The backside of this dish bears a green maker’s logo with the words “Made in Poland” and a serial number inscribed on it.

Verbilki Tea Set. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Verbilki Tea Set

“The white checked cups with saucers are very beautiful. They are thin and very elegant. Only three are left from a set of six. I got this set as a gift from my colleagues at medical school in 1986, when I turned sixty. Excellent china was the best gift for celebrations. My girlfriend who was charged with buying the present ran around the shops in Moscow for several days to find the best tea set.” —Prima Reitynbarg

CorningWare Coffee Pot. Collection of Irina Peris

CorningWare Coffee Pot

“We are the third generation of my husband’s family that has been in possession of this CorningWare coffee pot. I absolutely love it because I have the tendency to burn tea kettles and after numerous tea kettles were burnt and thrown out, I tried using this coffee pot as a tea kettle. Amazingly, none of the subsequent burning incidents put it out of business. So it’s been burned numerous times but it seems to be a magic, indestructible object. It used to have a rubber lid—but I discarded that. I don’t know if you’re supposed to boil water in it but it works perfectly for this purpose.” —Irina Peris

CorningWare Coffee Pot. Collection of Irina Peris

CorningWare Coffee Pot (close-up)

This close-up view of the coffee pot’s back side shows the immediately recognizable CorningWare logo and a blue floral design.

Tea Set. Collection of Irina Peris

Galina’s Tea Set

“This is my mother Galina’s tea set that my parents brought with them when they moved here in 2012, even though we have probably four different tea sets already. This one was given to my mother as a birthday present by her coworkers from the hydro-geology lab in the city of Bataisk, Russia, where she worked for twenty years. She was a chemical-engineer at the lab doing soil composition analysis. They had a beautiful environment there. I was very young when I saw it—it was all white with open shelves. On the shelves were clear glass vessels full of different soils and liquids, and also they were growing a lot of plants, which is the custom in Russian work-places. These modernist interiors that I see sometimes remind me of her work environment; all very light and airy with a lot of clear glass and crazy intertwining tubes and things bubbling with a lot of beautiful plants. They showed me wonderful experiments—“drop this into that and watch what happens”. They had wonderful parties, the ladies would go and fetch a torte and have tea parties, so the tea set makes perfect sense— a symbol of their companionship.” —Irina Peris

Tea Set. Collection of Irina Peris

Galina’s Tea Set (close-up)

The underside of this tea set is painted gold and reads “OLAFF,” which was one of the biggest suppliers of porcelain, ceramic, and glass ware in Russia.

Books

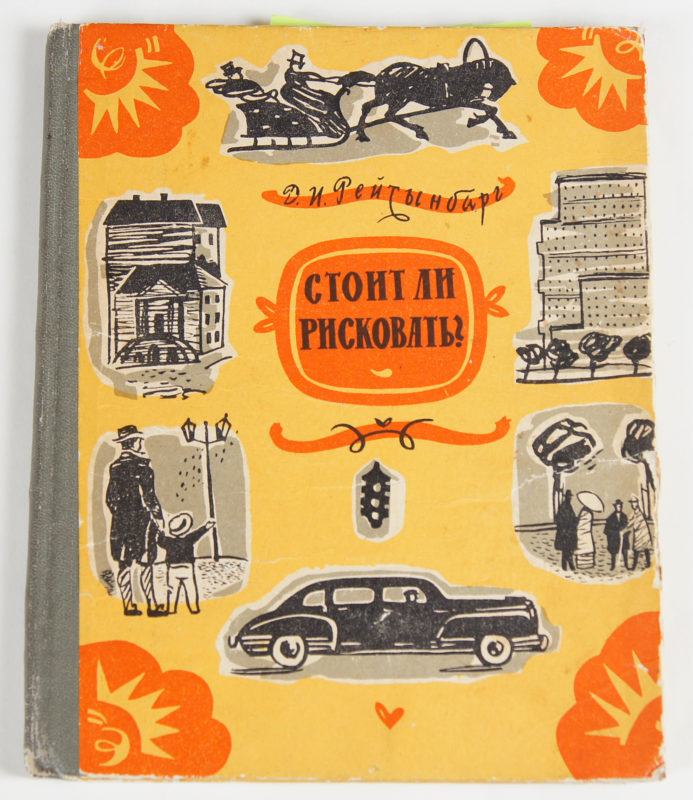

Book: Is it Worth the Risk? Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Russian Book: Is it Worth the Risk?

“This book for teenagers was written by my father, David Reitynbarg, in 1960. As a psychologist and psychotechnik* he took great interest in problems of safety, especially on production plants, factories, and in the streets. Street accidents and injuries absorbed his interest and attention. He studied the prevention of accidents caused by unnecessary risk. The book explained to children the difference between a meaningless risk–for example, to cross the street in front of moving transport–and necessary risk, a risk with a valid reason. For instance, the book tells children stories about real heroism—heroic acts and deeds about saving lives at the cost of one’s own life. The book tells much about the history of Moscow, its streets and transportation and the Moscow subway. As a result, children got to know safety rules and regulations in the street.” —Prima Reitynbarg

*Psychotekniks is a branch of psychology which has practical applications in economics, sociology, and other subjects.

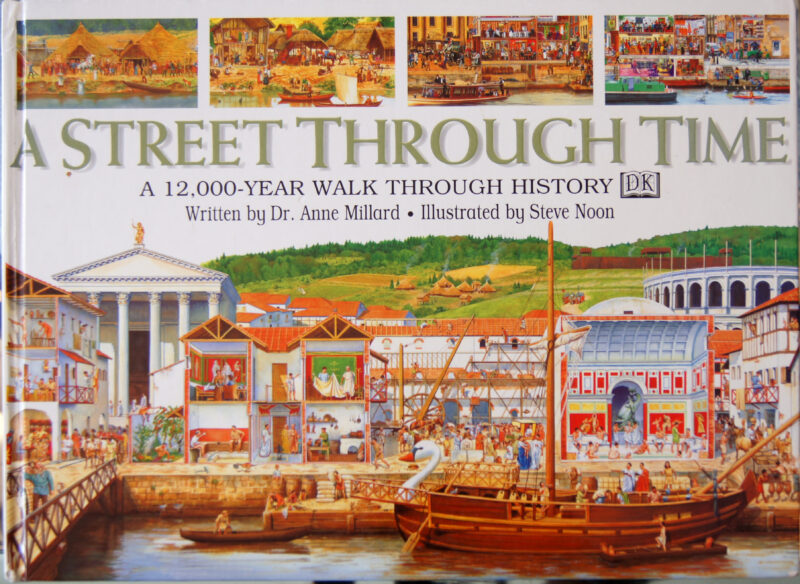

Cover of Sasha’s Book: A Street Through Time . Collection of Irina Peris

Book: A Street Through Time (Sasha’s Book)

“I forgot how old Sasha was when we bought this book, probably three or four, so it was before he was able to read, but he had already started tracing pictures. There is this figure that you can find who is hiding in different pages of the book, and it was very absorbing for Sasha. This probably was one of his first visual introductions to history and he is very much a history buff now.” —Irina Peris

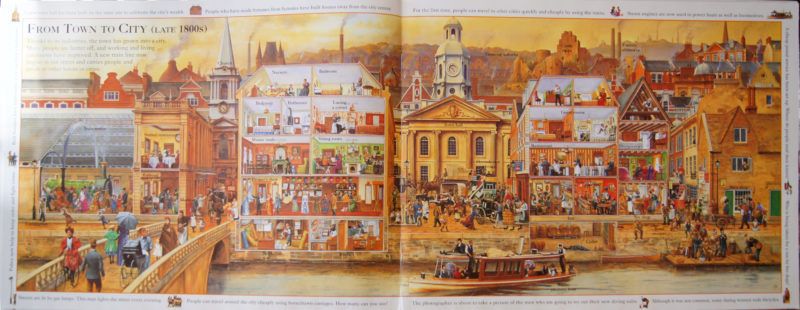

Book: A Street Through Time (Sasha’s Book). Collection of Irina Peris

Book: A Street Through Time (Sasha’s Book)

This is an interior view of the opened book. The illustration spans two pages and depicts a street in the late 1800s.

Sports and Games

Sochi sock. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

Sock from the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014

“I worked for an American television company during the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014. My title was Production Logistics Assistant. I worked within a team of five people. Our main job was to get broadcast equipment to venues, but really we did anything necessary to make the broadcasts happen. I was really happy to have these socks—they were very warm. I wore them almost every day: a cotton sock and then the wool Sochi sock on top.” —Ksenia Gushchina

Sochi IDs. Collection of Ksenia Gushchina

ID's from the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014

“It was an amazing experience for me and I met so many people from different countries—there was a guy who had worked sixteen Olympic games. I grew up watching the games. I like sport and dance, and figure skating was a combination of both. We actually got tickets to the huge final gala after the closing, all the competitors do a figure skating show, it was really hard to get tickets and we were sitting right there by the broadcasters. Our employer said that we did a great job and we were the best team he ever worked with.” —Ksenia Gushchina

Olympic Rug. Collection of Prima Reitynbarg

Olympic Rug from the 1980 Olympics in Moscow

“This Olympic symbol does not catch your eye when you are examining the carpet in the living room. You have to look for it. How did the Olympic symbol come to be on the carpet design? In 1980, Moscow received, in its international turn, the Olympic games. Grandiose preparations took place. The capital was cleaned up, the drunkards were exiled in order not to wallow or roll in the streets. Food and some deficit goods appeared in the stores. My colleagues and I were on a list of people invited to buy some so-called ‘deficit*’ goods, including rugs. We stood in line for a long time, paid not a little money, and got some things which we would not have been able to buy any other way. This shopping was considered a reward for our good work.” —Prima Reitynbarg

*Deficit means rare. In Russia in the 1980s, many consumer goods were hard to find.

Hobbies and Traditions

Model Airplanes. Collection of Irina Peris

Model Airplanes

“These are the model airplanes that my husband, Dan, builds with our son. My husband’s father was a hobby-pilot. My husband grew up in the back seat of his airplane. Aviation remains his interest and passion, even though he’s not related to it professionally. He buys these models to build with Sasha and ends up building them himself because Sasha often lacks the patience to finish.” —Irina Peris

Chess Set. Collection of Irina Peris

Chess Set

“This chess set sits on a table in the front room of our house, where three generations of men in our family gather and play. It’s not a precious object. I don’t remember where or how we bought it, but because of its transportability, it’s been very useful and well used. It was the chess set where my child learned how to play chess, watching how his grandfather and his father play each other. Sometimes they play three nights in a row, sometimes they don’t play for a month. Even though my husband speaks Russian, he and my father don’t have too many things that they do together. Chess is one of them, and for that reason it is an important bridge for them. When Sasha, my son, beats his dad at chess he is very proud.” —Irina Peris