Community Time Capsule: Italian American

Traditions

Wedding Gown, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Kathleen Vescio

Wedding Gown

Evelyn Brusco Vescio was married in this satin gown, which was made by her sister Ida, a seamstress. The dress has over 100 button loops, all of which were made by hand, as was the embroidery on the collar. Although largely responsible for domestic duties such as child rearing, many Italian American women also supported the family income by undertaking home crafts.

After her wedding in 1938, Vescio sent the dress back to the small town of Feroleto Antico in the Calabria region of southern Italy so that her niece could be married in a beautiful gown. World War II brought turmoil to much of southern Italy and severed ties between families still living there and those who had immigrated to America. Vescio assumed the dress was lost forever. Twenty years later, Vescio was shown a wedding picture of another Italian immigrant woman living in Pittsburgh. She excitedly exclaimed, “You are wearing my wedding dress!” The woman had received the gown from another bride in the village. It had apparently been passed around from bride to bride for many years. After sharing the story of the dress and a photo of her own wedding, Vescio convinced the woman to return the dress to the Vescio family.

Garden Snapshot. Collection of Alison Zapata

Garden Snapshot

“This photo was taken capturing a visit by a Pittsburgh Press photographer. My grandfather was an avid gardener. All of the neighbors in Swisshelm Park had fantastic gardens which they tended to daily. It was their routine and their passion. They traded vegetables, helped each other out, and competed a little. My grandfather planted corn seeds from a container of popcorn just to see what they would produce. Everyone was shocked when the stalks grew as high as the neighbor’s garage. It was a very big deal. My grandmother called the newspaper, who in turn sent out this photographer, and captured this moment. The headline for the photo read “A Corny Tale.” As you can see, there are beautiful and full tomato plants, a variety of peppers, and much more. About five in this picture, I remember helping to weed and take care of the garden. It was a labor of love. The love and pride shown by my grandfather is apparent.” —Alison Zapata

Presepio, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Ms. Theresa J. Colecchia, 94.43.1

Presepio

At Christmas, Italian American households in Western Pennsylvania come alive with tradition. For many Italian American families, a common holiday tradition is the display of the family presepio, or crèche. The word presepio comes from the Italian for enclosure, indicating the confined nature of the completed display. Originating in thirteenth century Italy, this tradition came to America with the immigrant tide and has since been passed on to younger generations. A typical presepio consists of a manger scene surrounded by a miniature village.

Made by Albino Albini, these buildings were part of the set that decorated the Albini family home in Vandergrift. A cabinet maker by trade, Albino took great pride in his family’s presepio and added a new piece every holiday season. Unable to secure a job as a woodworker, Albini worked in the local mill. Designing his presepio became his one creative outlet. Albino’s children, Fernando, Rose, and Sam, also assisted with designing, crafting, and painting new additions to the collection. For the Albinis, and many other Italian American families, setting up the presepio display was as important as trimming the Christmas tree. In some communities, Italian Americans traveled from house to house on Christmas Eve in order to admire the many presepi decorating the homes of their neighbors. The presepio was also commonly passed down from generation to generation, allowing younger Italian Americans to carry on the practice.

Food

Pasta Machine. Collection of Mary Lois Verilla

Pasta Machine

“This is my paternal grandmother’s spaghetti machine. The patent on it reads 1896. When I was a little girl, I would don my apron that she made me and she and I would make homemade spaghetti. It now has a place of honor in my kitchen and brings back fond memories.” —Mary Lois Verilla

Blue Gingham Apron. Collection of Mary Lois Verilla

Gingham Apron

“My paternal grandmother, Maria Fratangelo, made me this because I used to help her cook. She’s the person who taught me how to cook and, because of her, everyone considers me a good cook today. Many of her traditional recipes were handed down to me and are now made by my children. When I cook one of her recipes I always say, ‘My grandmother is smiling down from Heaven right now.” —Mary Lois Verilla

Chitarra, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Mrs. Dorothy A. Petrilli, 94.166.1

Chitarra

Although known as a chitarra (guitar) because of its wire and wood construction, this item is not a musical instrument. It is a pasta making device handmade by an Italian American resident of the Bloomfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh, modeled after a tool commonly used in the Abruzzo region of Italy. Many of the Italian immigrants who settled in Bloomfield came from the region of Abruzzo, located in south-central Italy. The device was purchased by the Petrilli family of East Liberty and used by four generations of the family.

Rolling Pin

Rolling Pin

To manufacture pasta using a chitarra, fresh dough was rolled over the chitarra wires using a rolling pin. The strips of dough—flatrather than tubular in shape—were then hung on wooden racks to dry. The resulting pasta, known as maccheroni alla chitarra, was a regional specialty. In the mountainous Abruzzo region, maccheroni alla chitarra was commonly served with a lamb and tomato sauce.

Food is one of the lasting elements of Italian American culture in Western Pennsylvania. The region is replete with family-owned Italian restaurants that were established during the age of immigration into the region. In Italian American homes, family recipes have been passed down for generations and continue to reflect Old World ingredients and traditions.

Music and Art

Zampogna, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Ken Marino, 96.50.1

Zampogna

Known as a zampogna in Italian, this set of bagpipes was handmade in Cessarentere, in the Abruzzo region of Italy. In the 1950s, the instrument was sent from family members still living in Italy to the donor’s father who was then residing in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Crafton Heights. It was an important family heirloom and reminder of the Old Country.

The zampogna is made from sheepskin turned inside out, to which is affixed a number of wooden reeds. Often decorated with yarn and tassels, it is held and played much like the better-known Scottish bagpipes. The Italian center of bagpipe culture is the town of Scapoli, located in the Molise region of Italy, where an annual zampogna festival is traditionally held. The instrument is also closely associated with the Christmas holiday.

Collage by Alison Zapata

Family Collage by Alison Zapata

“This work of art is a painting/collage based on the women in my life–my mother, my grandmother, and my great-grandmother–who passed away before I was born. I represented each at different periods of their life: childhood, motherhood, and as a grandmother, each in a different season. These women were all hard workers who put their family first. This is a tribute to their legacy.” —Alison Zapata

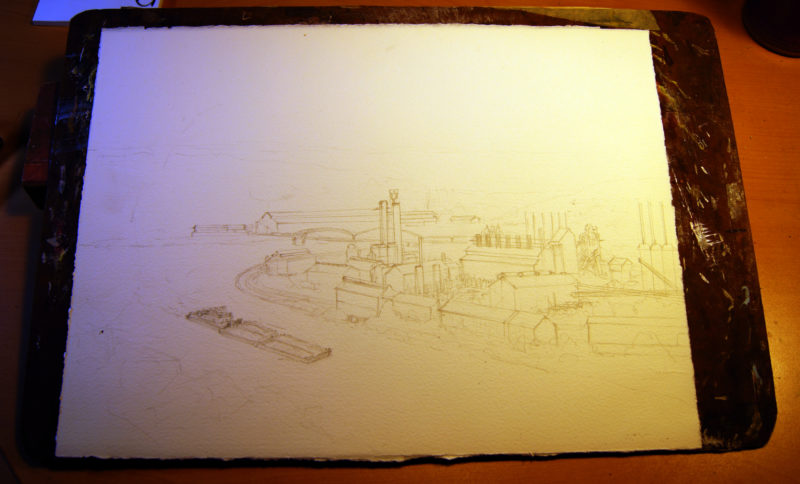

Drawing by Mary Lois Verilla

Drawing by Mary Lois Verilla

“This is a pencil sketch of a painting of the now defunct Duquesne Works. I’m known as ‘The Lady Who Paints Pittsburgh’ and am known for painting both current and historical landmarks of my hometown.” —Mary Lois Verilla

Painting by Mary Lois Verilla

While the City Sleeps, 2012, by Mary Lois Verilla

“I painted this skyline of Pittsburgh called ‘While the City Sleeps’ in 2012. This is a giclėe [high-quality digital print] of the original painting.” —Mary Lois Verilla

Slide Cabinet. Collection of Mary Lois Verilla

Slide Cabinet

“This is a slide cabinet containing my many pictures of Pittsburgh. Some were donated to me and some were taken by me on jaunts around Pittsburgh to capture scenes to be painted later in my studio. They were taken by me in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s and are willed to the Heinz History Center, the Trolley Museum, and the Steel Heritage Museum, depending on their subject matter.” —Mary Lois Verilla

Trolley Slides. Collection of Mary Lois Verilla

Trolley Slides

“These are examples of some of the slides of trolleys that I use as a reference when painting. My paintings are in many corporations and foundations in Pittsburgh, as well as all over the world.” —Mary Lois Verilla

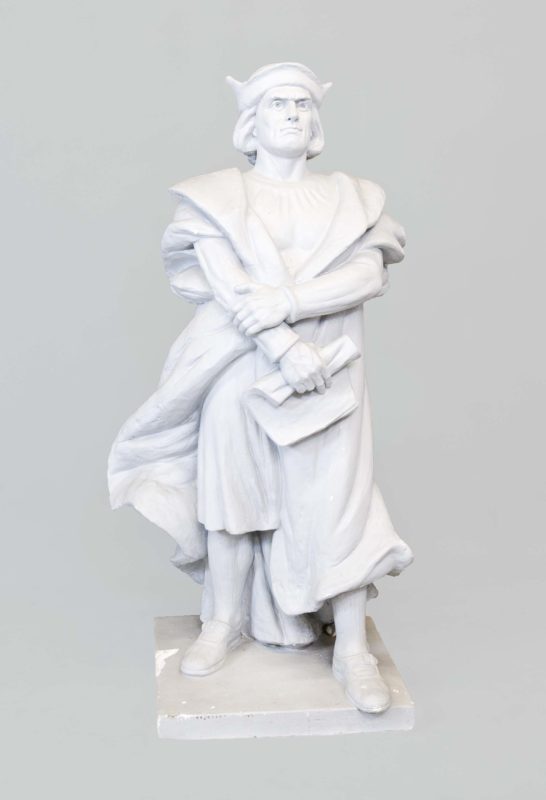

Columbus Cast, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Carla Scatena, 98.26.1

Columbus Cast

his plaster cast was used by Pittsburgh artist Frank Vittor (1888-1968) to cast his famous bronze statue of Columbus, currently located in Schenley Park. An immigrant from northern Italy, Vittor came to Pittsburgh in 1918 after working in New York under New York architect Sanford White. He was known as the “Sculptor of Presidents” and was the founder of the Pittsburgh Society of Sculptors. Vittor’s war memorials, commemorative plaques, decorative fountains, and roadside landmarks are located throughout the Pittsburgh region. His Columbus Statue, dedicated with the support of the Sons of Columbus of America, has long served as a landmark of the Italian American community.

The body of Vittor’s work illustrates the process of assimilation, as the artist struggled to identify as both an American and an Italian—a dilemma faced by many recent immigrants. He developed a reputation for his work on distinctly American subjects, such as his many presidential sculptures and his timeless statue of German American baseball great Honus Wagner, located at PNC Park on Pittsburgh’s North Side. However, he never forgot his immigrant roots and often worked with local Italian community groups to depict local Italian American leaders, as well as Italian icons such as Christopher Columbus and Guglielmo Marconi.

Family Heirlooms

Steamship Trunk, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Angela Pasquale, 95.26.4

Steamship Trunk

Two generations of the Cavaliere family used this wood and leather Belber wardrobe trunk in their transatlantic travels between Italy and the United States. The donor’s grandfather, Angelo Cavaliere, came to the United States in the early 1920s and worked on the Pennsylvania Railroad. When he returned to Naples, he used this trunk to bring his belongings back to Italy. The donor’s mother and father, Rosa and Fortunato Cavaliere, then used the trunk when they immigrated to America.

The quintessential symbol of immigration, the steamship trunk conjures images of loss, longing, separation from family and friends, and the journey to a new and unfamiliar land. Immigrants from Italy who made the voyage were forced to pack their previous lives in the small confines of a trunk. The few personal articles they managed to bring with them included clothing, religious objects, family photos, cooking utensils, and other personal effects.

Most Italians entered the United States through the immigrant processing station at Ellis Island. There, people hoping to start a new life in America underwent a rigorous screening process designed to keep out ‘undesirable’ immigrants. They were checked for contagious and infectious diseases and for any physical or mental abnormality before being granted access to the American mainland.

Swaddling Cloth, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Mrs. Frances DiLeonardo, 89.36.15

Swaddling Cloth

Nicholas DiSilvio was wrapped in this elegant swaddling cloth as a baby living in Pescocostanzo, a mountain town located in the Abruzzo region of Italy. He brought it with him when he immigrated to the United States in 1887. His daughter stated that it was handled with “great care” and that it had “great sentimental value” as one of only a handful of possessions brought from the Old Country.

A swaddling cloth is a long length of fabric, usually cotton or wool, which was wrapped around an infant’s legs. It was believed that securing an infant’s legs together helped them to grow straight. Italian American families also believed that the swaddling cloth would protect newborn children against the malocchio, or evil eye, which according to superstition brought harm to the young.

Community

Ateleta Beneficial Association Flag, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Phil Mastroiani for the Ateleta Beneficial Society, 99.4.1

Ateleta Beneficial Association Flag

Italian immigrants tended to identify themselves not by country of origin, but the region, province or town that they left behind. Stemming from the country’s long history of occupation by foreign powers and its relatively recent unification (1870), this strong sentiment of regionalism, known as campanilismo, governed the formation of mutual aid societies. These organizations, which helped to ease the transition to life in America and offered financial support to members in need, were commonly reserved only to immigrants hailing from a particular town or region in Italy.

The Ateleta Beneficial Association was founded by immigrants hailing from the small mountain town of Ateleta, in the south-central region of Abruzzo. Many found work in Pittsburgh in the building trades, and the organizational members soon erected an organizational building on Cedarville Street in the Bloomfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh. The club soon became an important social and cultural center for its members and other Italian immigrants in Pittsburgh.

On September 21, 1927, the fledgling organization held a special ceremony to dedicate this Italian flag containing the name of the organization and commemorating the founding of the club. The flag adorned the interior of the Ateleta Beneficial Association for nearly 80 years, and was used for special activities and events celebrating Italian culture. Although it no longer serves its original function as a mutual aid society, the Ateleta Beneficial Association still exists as a social club for people of Italian ancestry. A women’s auxiliary organization, the Ateleta Women’s Association, also continues as a popular social club in Bloomfield.

Cornerstone, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Petrina A. Lloyd, 98.80.2

BSNI Cornerstone (front-view)

This cornerstone served as a time capsule for the Beneficial Society of North Italy (BSNI), a mutual aid organization located in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. The BSNI was founded in the 1930s by Italian immigrants hailing from Veneto, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Lombardia, Piemonte, and other regions in the north of Italy. Although the vast majority of Italian immigrants hailed from the south, a small but significant population of northern Italians also made the greater Pittsburgh region their home.

When BSNI members were constructing their club building in the 1940s, they placed a small copper box containing the organizational bylaws book and a list of the founding members of the lodge and its women’s auxiliary inside this cornerstone, which was then built into the façade. The time capsule remained untouched over the next fifty years.

BSNI Cornerstone: Date, , Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Petrina A. Lloyd, 98.80.2

BSNI Cornerstone (side-view)

During its heyday in the period from the 1930s–1960s, the club was the scene of banquets, wedding receptions, dances, ethnic festivals, and other special events. It also provided a place where immigrants gathered to play bocce and other Old World games. In the 1940s, the Italian heavyweight boxer Primo Carnera, who hailed from the same northern Italian province as many of the BSNI members, made a point of visiting the club whenever his career took him through Pittsburgh.

Due to the forces of assimilation and the declining desire or need for such organizations among the younger generations, the BSNI decided to sell their building in the late 1990s. In order to preserve the history of the organization, Ed Paraggio, the son of a founding member of the BSNI, removed the time capsule from the building just before it was sold.

Sash, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Anthony DiNardo, 2011.80.1

Sons of Columbus Sash

With one of the largest concentrations of Italian immigrants in the United States, Pittsburgh was the birthplace of two Italian fraternal organizations that eventually became national in scope—the Italian Sons and Daughters of Pennsylvania, and the Sons of Columbus of America, Inc. Founded in 1925, the Sons of Columbus provided financial assistance to immigrants in need by providing financial assistance to members in need while also helping to preserve traditions of the Old Country.

Following the ceremonial costuming traditions common in their native land, Sons of Columbus members wore fraternal regalia such as this red sash during meetings, special events, and in their annual Columbus Day procession. This particular sash identified its wearer as a national commissioner—an organizational officer involved in the decision-making of the national organizational body that oversaw the many regional chapters of the Sons of Columbus. The Sons of Columbus has long been active in celebrating Columbus Day in Pittsburgh.

Religion

Baptismal Font, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Joanna Vento, 2000.61.1

Baptismal Font

This Baptismal font was used by Rev. Anthony DiStasi to baptize Italian American members of Trinity Presbyterian Church. Located on Larimer Avenue in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Trinity Presbyterian Church was originally called the First Italian Presbyterian Church of Pittsburgh.

At the turn of the twentieth Century, the Presbyterian Church recognized that the flood tide of European immigrants to the United States represented a large body of people that might benefit from the church’s teachings. As a result, Presbyterian churches in American cities began to actively convert Italian immigrants by establishing outreach missions in neighborhoods populated by large numbers of foreign-born Italians.

In 1892, the well-established East Liberty Presbyterian Church established a mission on Larimer Avenue, one of the city’s many Little Italy communities. Some Italians, disenchanted with the teachings of the Catholic Church, were attracted to Presbyterianism. Others joined the church after gradually learning more about it through church-sponsored English language and Americanization classes offered in their neighborhoods.

In 1899, the Presbytery of Pittsburgh reorganized the prosperous mission into the First Italian Presbyterian Church of Pittsburgh and, in 1903, erected a church at the corner of Larimer Avenue and Mayflower Street. The congregation eventually became Trinity Presbyterian Church. Throughout the course of the 20th century, the church provided a place for religious rites of passage for the Italian Protestant population of Pittsburgh. It closed in the early 2000s.

Baptismal Gown, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Anita Sanvito, 99.72.1

Baptismal Gown

This handmade silk baptismal gown and a matching pillow were brought to the United States in 1913 by Lucia Sanvito, an Italian immigrant from the southern Italian region of Molise. The regions of Molise and neighboring Abruzzo were known for their silk and lace craftsmanship. Five of Sanvito’s children were baptized in Italy while wearing this gown. It was one of the few personal belongings that the family brought when they emigrated from Italy to McKees Rocks. At the time, Sanvito planned to use the gown for the baptism ceremonies of additional children which she expected to have in America. They had two sons, Anthony and Martin, but Sanvito and her husband never saw their baptisms; both parents died during the influenza epidemic of 1918, which killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide. The effect of the flu in the US was so severe that the average lifespan of Americans dropped by 12 years.

For Italian immigrants, Catholic rites of passage such as bBaptism, hHoly cCommunion, and mMarriage were important events of the life cycle. In the baptismal ceremony, children were carried to the altar by their godparents while wearing a baptismal gown and resting on a baptismal pillow. As in the case of the Sanvito family, the gown was used for all children, regardless of sex. The birth parents looked on during the ceremony, which was commonly followed by a family and community gathering at the home.

Crocheted Baptism Blanket. Collection of Mary Lois Verilla

Baptism Blanket

“My paternal grandmother, Maria Fratangelo, made this for me for my baptism. It was also used as a coverlet for my crib. It is now seventy-nine years old and in excellent condition.” —Mary Lois Verilla

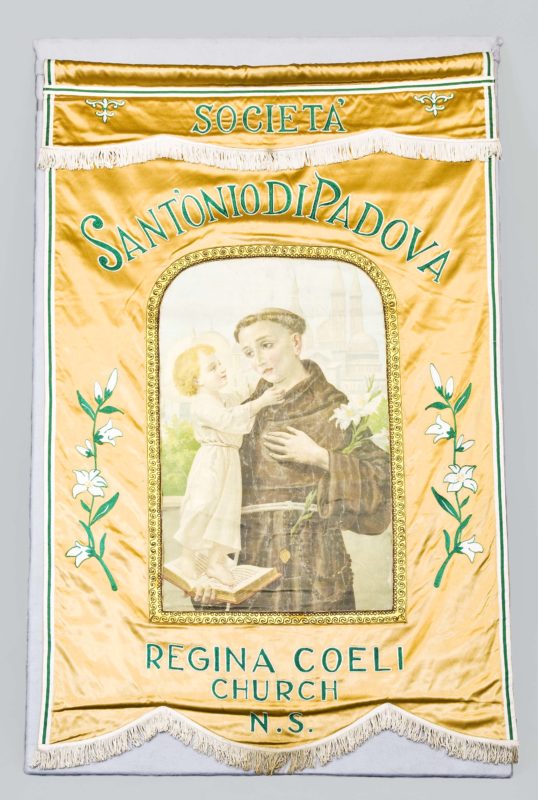

San Antonio Banner, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of The Catholic Store, 99.95.1

San Antonio Banner

The veneration of Saints was an integral element of Italian American religious tradition. This banner honoring the life of Saint Anthony (San Antonio) of Padua adorned the Regina Coeli Catholic Church, located in the Manchester neighborhood of Pittsburgh’s North Side. The banner was brought out of the church for special occasions, including an annual festival held in honor of Saint Anthony. San Antonio, whose tomb is in the northern Italian city of Padua, near Venice, is a particularly popular saint for the Italian people. His images are ubiquitous in churches throughout the country.

Regina Coeli opened its doors in 1905 in order to accommodate the religious needs of Italian immigrants who migrated to the North Side from their original places of residence in downtown Pittsburgh. The church celebrated its last mass in 1992.

When arriving in Western Pennsylvania, Italian immigrants brought with them their unique Catholic religious traditions which included pageantry, processions, and veneration of saints. These traditions were met with skepticism by early immigrant Catholic groups, including Irish and German settlers. For this reason, many Italian immigrants opened churches of their own. Regina Coeli was one of many Italian ethnic parishes in the Pittsburgh region. In time, Italian migration to the suburbs resulted in the demise of the majority of the “Little Italy” neighborhoods, and many of the Italian churches closed their doors.

San Rocco Statue, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Cathy Costa Fusca, 96.1.1

San Rocco Statue

In 1931, Joseph Costa brought this statue of San Rocco (Saint Roche) to Pittsburgh from his hometown of Maierato, Calabria. In the 1930s and 1940s, the statue was carried through the streets of the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh as part of the community’s annual San Rocco festa, or feast day. At the time, the area along Larimer Avenue was heavily populated by Italian Americans. The local Italian Catholic Church, Our Lady Help of Christians, was located on Meadow Street.

In Italy, most municipalities have a patron saint who is celebrated each year on a particular day. Saint Rocco was a popular Saint for the immigrants of Western Pennsylvania and numerous Italian communities in the Pittsburgh area held San Rocco festivals. In addition to the group from Calabria living in East Liberty, the people from the town of Roccacinquemiglia living in Bloomfield held a San Rocco festival, as did the immigrants from Patrica living in Aliquippa, a town about twenty miles northwest of Pittsburgh. Today, the Aliquippa San Rocco festival continues as one of the longest continuously practiced Italian festivals in the United States. The festa consisted of a solemn mass at Our Lady Help of Christians in which the homily chronicled the life of San Rocco, the patron saint of those afflicted with contagious and infectious diseases, such as the plague. The festa also included a street procession in which the statue was carried through the streets for all to venerate, as well as plentiful Italian food, games like bocce, and a grand fireworks display.

The statue shows San Rocco with an open sore on his leg (a lesion from the plague), a walking staff in hand (illustrating his pilgrimages through Italy), and a small dog (who purportedly nursed him back to health by bringing food during his illness) at his side.

Tools and Work

Shoe Last, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of J. Dino DePaulo, 2005.127.1

Shoe Last

Guy “Ton” DePaulo used this shoe last to repair shoes at his shop on Bessemer Avenue in East Pittsburgh. Born in Naples, Italy, DePaulo immigrated to the United States in 1920. After learning the shoe repair trade from his uncle, DePaulo started his own repair shop while also working at nearby Westinghouse Air Brake Company. The two jobs allowed him to make ends meet.

The shoe last—a device to hold shoes in place while exposing the soles so repairs could be made —was one of DePaulo’s most-used tools. For over seventy years, Ton’s Shoe Shop was more than just a business. It was an active social center of the neighborhood where people gathered together to discuss politics, sports, and other news of the day. Italian immigrants relied on strong interpersonal relationships with their countrymen and familial ties in order to earn a living in their adopted homes. Immigrants commonly learned a trade or skill from a family member or friend. Sometimes, family and community ties formed business partnerships which allowed immigrants to pool resources.

Blade Sharpener, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of the Antonucci family in memory of Francesco Antonucci and his grandchildren, 94.170.01

Blade Sharpener

Francesco Antonucci used this handmade machine in order to earn his living sharpening knives and scissors door-to-door on the streets of Pittsburgh. He carried the grinding machine on his back through the neighborhoods, using a bell to announce the arrival of the “L’Arrotino,” or “sharpening man.” The machine has a grinding stone which is attached to a rubber belt operated by a foot pedal.

Antonucci was born in the town of Ginestra degli Schiavoni in the Campania region of southern Italy. He arrived in the United States in February of 1912, at the age of 26. He first lived in St. Louis, Missouri, but moved to Pittsburgh around 1917. Antonucci walked and took the streetcar in order to offer his services throughout the many neighborhoods in Pittsburgh—including the Hill District, Braddock, Oakland, East Liberty, and Highland Park. He attached the machine to his back with two leather straps and carried it all day long. He commonly left his house at six o’clock in the morning and returned home around four o’clock in the afternoon. He also repaired broken umbrellas. Antonucci earned a modest living as the L’Arrotino, managing to support a large family of ten children on his income.

Italian immigrants developed a reputation for their specialized skills, and gravitated to certain trades including shoemaking, barbering, and tailoring, among others. Door-to-door work was also common among Italian immigrants. Some operated peddling businesses selling produce; others plied a trade or skill in the Italian neighborhoods of the city.

Sickle, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Guido Cardillo, 95.127.1

Sickle

Guido Cardillo, an immigrant from the town of Spigno Saturnia in central Italy, brought this sickle with him when he came to Pittsburgh in 1956. Cardillo used this sickle to cut down wheat and other agricultural crops in his home town in Italy. In Pittsburgh, he used it in his work as proprietor of a local landscaping business.

Most Italian immigrants who came to the United States in the great migration period (1880s-1950s) hailed from small agricultural communities in the southern part of Italy. Italian families were usually subsistence farmers who raised crops on small lands owned by absentee landowners. In the first decades of the twentieth century, the Italian peninsula endured numerous environmental hardships such as disease epidemics and recurring natural disasters, namely floods and droughts, which made an agricultural existence increasingly untenable. As a result of the economic depression that resonated throughout post-WWII Europe, large numbers of agricultural workers flocked to the United States in search of work.

Most Italian immigrants—because of their bad experiences as farmers in the Old Country—found employment in industries other than agriculture. Some, however, stuck to their agricultural roots and found ways of making their knowledge in this area work for them in America. A good number of Italians in Pittsburgh, for example, entered the landscaping businesses and opened small family-owned companies that cared for the yards of the wealthy.

Thinning Scissors, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Lina Insana, 2006.61.1

Thinning Scissors

Franco Insana used these thinning scissors as the owner and chief instructor at Franco Beauty Academy, a beautician training school located in downtown Pittsburgh. An immigrant from Sicily, Insana started the school in 1950 and later opened branches in New Kensington, Charleroi, and Ambridge, three towns within a thirty-mile radius of Pittsburgh.

A gregarious and likeable personality, Franco Insana was known throughout the city of Pittsburgh for his blindfold haircuts, which he used as publicity stunts for his business and for raising money for his favorite cause, the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. Insana also invented and patented a special plastic rod for styling permanent waves. Insana’s business was so successful that when he returned to Sicily for a visit, he brought with him a new car—a sign to his family and friends that he’d achieved the American Dream.

Insana’s wife Nina, also born in Sicily, was instrumental in managing the business and financial affairs of the school and served as proprietor from the time of her husband’s death in 1974 until the business closed its doors in 1989.

Miner’s Helmet: Side View, , Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Richard Furgiuele, 2001.89.2

Miner’s Helmet

This crushed helmet saved the life of its owner. A second generation Italian American whose parents came to Western Pennsylvania from Italy in search of work, Richard Furgiuele wore this helmet in the 1940s during his work with the Redlands Coal Company in rural Indiana County. One day, while driving a shuttle car into the mine, Furgiuele’s head became lodged between the low roof and the steering wheel of his vehicle, crushing his protective headgear. It took safety workers over an hour to free him.

Miner’s Helmet, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Richard Furgiuele, 2001.89.2

Miner’s Helmet (side-view)

During the peak immigration years of 1890–1930, thousands of Italian immigrants were drawn to Western Pennsylvania by one industry—coal mining. Bituminous coal mined in the Pittsburgh region was used to heat homes, run railroads, power ships, provide electricity, operate industrial machinery, and manufacture coke—the high-energy material needed to manufacture steel.

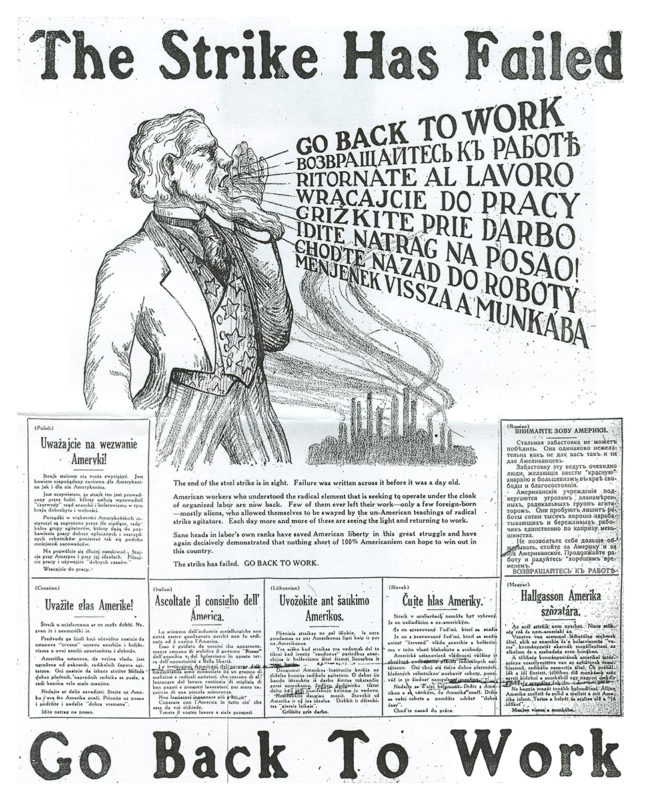

“The Strike Has Failed” Newspaper Ad

“The Strike Has Failed” Newspaper Ad

Italian immigrants to Western Pennsylvania entered a wide variety of industrial jobs, namely in mines and mills. Italian workers performed many of the jobs necessary for Pittsburgh steel mills to operate. Some mined coal and worked at coke ovens. Others laid track on the spur railways that transported raw materials and finished products to destinations off the main track. Still others worked directly in the steel mills, performing a wide array of essential tasks. They worked long hours in hazardous conditions for low pay, but still found the work rewarding as they received a paycheck and a promise for a better future for their children and grandchildren.

Facing the difficulties of working in the steel industry and its interconnected subsidiary industries, Italian immigrants gravitated to the organized labor movement. In 1919, labor leaders in Pittsburgh organized a nationwide strike involving over 350,000 steelworkers. The strike eventually failed, partly due to a massive company media campaign targeting the immigrant strikers, who formed an important part of the workforce. These ads used the Uncle Sam image of America to question the patriotism of the immigrant worker. In this ad, Uncle Sam implores immigrant workers to “Go Back to Work” in numerous European languages, including Italian, Polish, and Hungarian.. The strike was also hindered by an aggressive campaign by the Pennsylvania State Police, who were charged with preserving order amongst the immigrant workers.

Despite its failure, the Steel Strike of 1919 was an important step in the organization of the steel industry and demonstrated the increasing involvement of immigrants in the cause of American organized labor.

Sports and Games

Bocce Balls, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Josephine M. DeLillo, 94.96.1

Bocce Balls

These worn and weathered bocce balls show signs of extensive use on the bocce courts of New Castle, Pennsylvania, a city which has one of the densest concentrations of Italian Americans in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. A bowling sport of precision and accuracy, bocce was popularized by Italian immigrants who settled in Western Pennsylvania at the turn of the twentieth century.

The sport impacted many aspects of Italian American life. To assuage fears of thunder, Italian American women commonly told their children it was only St. Peter playing bocce. This practice illustrates the role of bocce within many facets of life, including family, religion, and community. Italian immigrant mutual aid societies built and maintained bocce courts, as did many homeowners. Annual religious feast days, known as feste, often culminated in grand bocce tournaments, drawing young and old alike. Realizing the centrality of bocce, many Italian American authors, including poet Felix Stefanile, incorporated bocce references into their works.

By providing a venue for socialization, bocce helped to preserve the customs and language of the Old Country. For the younger generations, the sport provided an opportunity to forge interpersonal relationships with their elders and provided an important link to their cultural past.

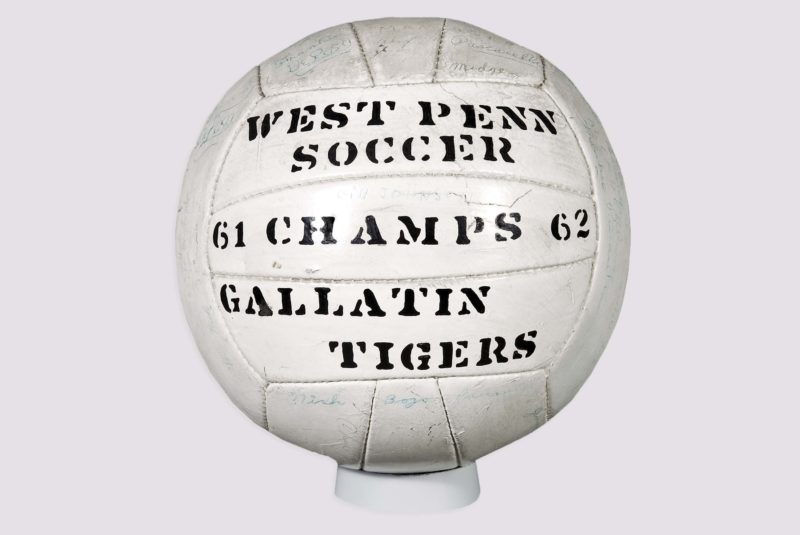

Soccer Ball, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Alex Pascarella, 2003.131.7

Soccer Ball

Italy has long been recognized as a country that has historically embraced and excelled at the sport of soccer. This soccer ball belonged to Alex Pascarella, an Italian American from the small Monongahela River community of Gallatin (Washington County) who played for the local soccer team from the 1940s through the 1960s. During this period, the greater Pittsburgh region was a national powerhouse in the sport of soccer. For immigrant coal miners and their descendants, soccer afforded a temporary respite from the day to day toil of industrial work. Popular in Europe in the first part of the twentieth century, soccer was brought to Western Pennsylvania with the European immigrant tide.

In 1942, prolific goal-scorer Alex Pascarella led the Gallatin Tigers to victory in the United States National Open Championship tournament, in which they defeated Pawtucket, Rhode Island. The team from Gallatin consisted largely of people of Italian descent who were drawn to the region by the prospect of work in the area coal mines. The title was the first of many national championships for soccer clubs from the Pittsburgh region.

Pascarella continued to play soccer for the next two decades. In 1962, he and his son Nicholas were teammates on the Gallatin team that captured the West Penn League championship title. Pascarella kept this ball used in the championship match. It is signed by all the members of the team.

Franco's Italian Army Items, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Albert Vento, Sr., 2003.166.1, 2003.166.3, 2003.166.3; museum purchase, 2000.18.1; and gift of Jamie Pennisi, 2004.111.1.

Franco’s Italian Army (seat cushion)

From a small group of Pittsburghers of Italian descent who regularly attended Steeler games, Franco’s Italian Army grew into a nation-wide fan phenomenon in the 1970s. The group traveled to games, Italian food and wine in tow, and cheered on Steeler running back Franco Harris from their seats in Sections 29 and 30 at Three Rivers Stadium.

Franco's Italian Army Items, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Albert Vento, Sr., 2003.166.1, 2003.166.3, 2003.166.3; museum purchase, 2000.18.1; and gift of Jamie Pennisi, 2004.111.1.

Franco’s Italian Army (metal helmet)

The fan group began in 1972 when local Italian Americans learned that rookie running back Franco Harris’ mother was an Italian immigrant. The army was led by “generals” Tony Stagno and Albert Vento. Football, Franco, and their shared heritage bound them together.

Franco's Italian Army Items, Senator John Heinz History Center, Gift of Albert Vento, Sr., 2003.166.1, 2003.166.3, 2003.166.3; museum purchase, 2000.18.1; and gift of Jamie Pennisi, 2004.111.1.

Franco’s Italian Army (scarf)

In the 1970s, the children and grandchildren of Italian immigrants began to warmly embrace a shared immigrant heritage that early Italian immigrants had tried to hide. Nationwide, this so-called “New Ethnicity” movement led to widespread public displays of ethnic pride, including the formation of cultural organizations, the resumption of ethnic festivals that had gone dormant, and a general interest in reconnecting with one’s ethnic roots. In Pittsburgh, ethnic expression came in the form of football fanaticism.