Community Time Capsule: Carpatho-Rusyn American

Religion and Community

Virgin Mary Vitrine

Virgin Mary Vitrine

This vitrine shows the Virgin and Child with a nun and monk kneeling in adoration. Below, it features a rotating scroll that can be turned using a handle on the side to display one of several images depicting major feast days such as Ascension and Pentecost. This vitrine is representative of the type of icon that can be seen in many Carpatho-Rusyn homes in the US, the fact that this particular style of icon was in a Carpatho-Rusyn home is an example of a distinctly immigrant phenomenon. Eastern religious icons tend to be flat paintings rather than three-dimensional statues or vitrines, and while the Virgin Mary is important to all branches of Christianity, her iconography is different in the East. For example, in the Eastern tradition she wears blue and maroon robes. In addition, the decorations at the bottom of the vitrine show the Sacred Heart, which is venerated in the Western church but remains a point of controversy in the Eastern Church. John Righetti, president of Pittsburgh’s Carpatho-Rusyn Society, guesses that this style of inexpensive icon was imported in large quantities with immigrants as the target consumers.

Virgin Mary Vitrine: Close-Up

Virgin Mary Vitrine (close-up)

This vitrine came to the Carpatho-Rusyn Cultural Center from Lina Kortyna of Washington, Pennsylvania. It belonged to her grandmother Elizabeth Bresnay, a Carpatho-Rusyn woman who immigrated to Primrose, a coal town about twenty miles southwest of Pittsburgh. Bresnay was from the village of Ubrez, in Uzh County (today in Eastern Slovakia). The vitrine hung in her living room in Primrose and her neighbor, also a Carpatho-Rusyn Greek Catholic, had one as well.

Lodge Insignia: Front View

Lodge Insignia

These ribbons and badges are examples of insignia worn by men, women, and children who belonged to local lodges and brotherhoods in Pennsylvania. People would wear the colorful side to parades and events and the black side for funerals.

Lodge Insignia: Reverse View

Lodge Insignia (view of back)

Some of the ribbons seen here have information displayed in both Cyrillic and Latin type. Many also show the Virgin Mary; Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius, who brought Christianity to the Slavic peoples; or the Byzantine cross. Several also have a small image of two hands shaking, symbolizing the fraternal bond of these organizations.

Lodge Insignia: Close-Up

Lodge Insignia (close-up)

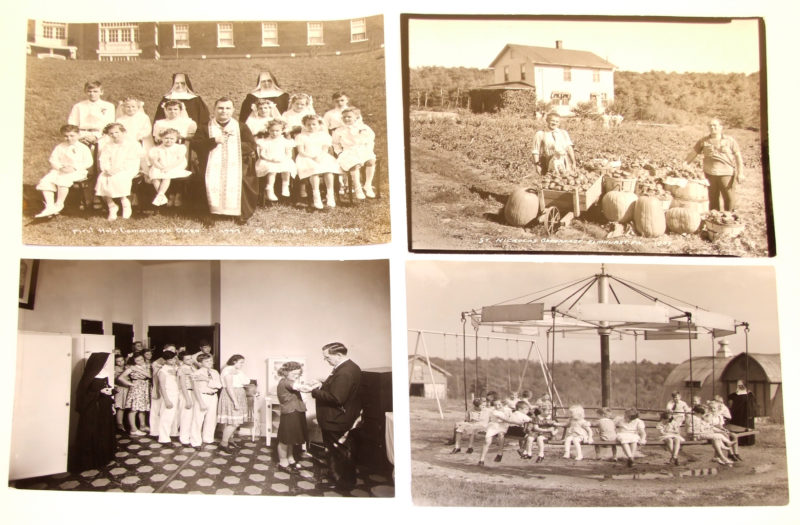

Life at St. Nicholas Orphanage. Photos. Collection of the Greek Catholic Union

Life at St. Nicholas Orphanage

This set of pictures depicts life at the St. Nicholas Orphanage. Top left: children with two of the sisters and a priest. Top right: The orphanage had a farm, which produced the pumpkins seen here. Bottom left: children lining up to receive a vaccine—the children have their sleeves rolled up in preparation. Bottom right: children riding on a playground carousel.

Letterpress Blocks and Printed Images. From the collection of the Greek Catholic Union.

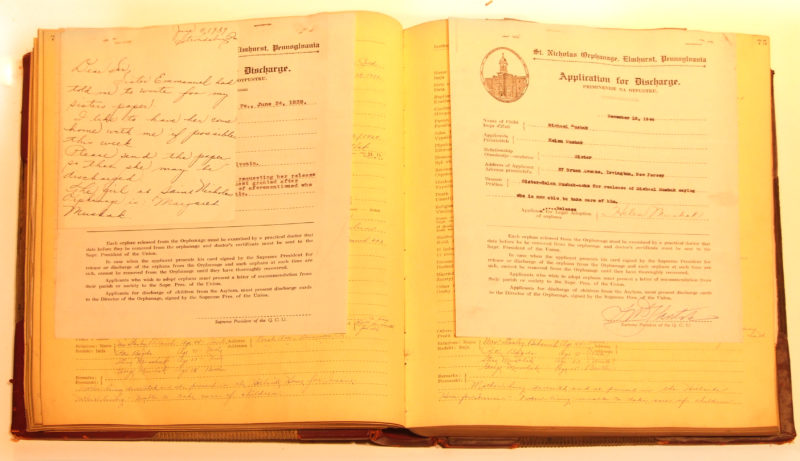

St. Nicholas Orphanage Release Papers with Note

This is a record from the collection of the Greek Catholic Union of the release of Margaret Muskak from the St. Nicholas Orphanage, with an accompanying note written by her sister. Take a closer look at the right-hand page: the slip is printed in both English and Carpatho-Rusyn (written in the Roman alphabet rather than in Cyrillic). The note attached to the left-hand page says:

June 11, 1939 Stroudsburg, PA

Sister Emmanuel had told me to write for my sisters [sic] paper. I like to have her come home with me if possible, this week. Please send the paper so that she may be discharged. The girl in Saint Nicholas Orphanage is Margaret Muskak.

Traditions

Pysanky: Eighteen Easter Eggs

Pysanky: Eighteen Easter Eggs

Pysanky are brightly colored Easter eggs decorated using a wax-resist technique similar to batik. The term comes from the Slavic word pysaty, “to write,” which references the way people draw on the eggs with wax. The Carpatho-Rusyns have a variety of pysanky styles, but one distinct style is made with colored wax that is used to create the designs using short strokes resembling teardrops. There are many legends and traditions surrounding these eggs, including beliefs that decorating eggs with certain patterns could serve specific purposes. For example, spiral designs were meant to trap evil spirits, while the girls would give eggs with hearts on them to boys they liked. Eggs were given as part of special baskets presented to friends, family, and community leaders on Easter Day, but were also used to ward off evil, for example, when placed near beehives to ensure a good harvest, or when kept in the home for protection from fire, lightning, and storms. A great deal of this meaning has disappeared from modern pysanky, as many artists today simply copy designs from books. This egg carton contains a variety of pysanky, in various Carpatho-Rusyn styles as well as hybrid styles that involve pre-decorated shrinkable plastic sleeves.

Pysanky: Silver Warhol Easter Egg

Pysanky: Silver Warhol Easter Egg

This egg was decorated as part of a demonstration of pysanky-making at The Andy Warhol Museum during its annual Carpatho-Rusyn event that took place from 1998 to 2006. Its color pays tribute to the silver walls of Warhol’s Factory. Carpatho-Rusyn Society member, Helen Timo used Crayola crayons to achieve the colors of wax seen here, and received enthusiastic help from her husband, John, with spray-painting the egg.

Pysanky: White Easter Egg with Sun Motif

Pysanky: White Easter Egg with Sun Motif

This is a contemporary pysanky egg made in Eastern Slovakia. While the yellow design may look like a flower, this shape is traditionally is used by Carpatho-Rusyns to denote the sun. The sun has been an important symbol for the Carpatho-Rusyns since before their conversion to Christianity in the ninth century. Other symbols used to decorate pysanky include the swallow, a symbol of spring; the spider, which is thought to bring good luck; and a sheaf of wheat, a symbol of fertility.

Pysanky: Helen Timo Teaching her Technique

Pysanky: Helen Timo Teaching her Technique

In addition to being a prolific pysanky artist herself, Helen Timo passed her techniques, both traditional and innovative, on to many others. Here, Caroline Dilli, a relative, holds a Speedball calligraphy pen while Timo demonstrates the proper grip using a pencil. You can also see a printout of various egg designs on the table. Over the years, Timo and her students demonstrated many times at The Warhol, inspiring a silver egg included in this collection.

Easter, 1987

Easter, 1987

In this photo, a very young Maria Silvestri helps her grandmother, Helen Timo, with a basket full of pysanky. Through teaching, Timo passed the centuries-old tradition of pysanky-making on to the next generation.

Pysanky: Tools for Wax Melting

Pysanky: Tools for Wax Melting

These are tools for melting wax to make pysanky. One of Helen Timo’s technical innovations was using a hot plate as a heat source, which enabled her to work on a large table rather than staying close to a stove. This meant she needed small-scale containers that could stand up to heat, like the miniature cast iron pan. The small silver container seen here is the empty metal cup from a tea light. Timo reused several of these at a time to hold beeswax melted together with Crayola crayons, creating a broad palette of colors.

Pysanky: Pens with Spot Remover and Lighter Fluid

Pysanky: Pens with Spot Remover and Lighter Fluid

Helen Timo used these Speedball calligraphy pens, lighter fluid, and spot remover to make pysanky. The traditional tool for applying the wax to eggs is little more than a stick with a small tip attached with wire or string. Timo’s innovation was to use Speedball calligraphy pens, which feels more natural in the hand and allow for greater control of the wax. She also discovered that when practicing the line technique—in which you draw patterns with wax, dip the whole egg in dye, and then remove the wax, leaving white lines—she could use Zippo lighter fluid or Energine spot remover to get the wax off rather than melt it off over a candle. Her granddaughter Maria says of this improvement in efficiency, “My grandmother had life to happen and more eggs to make!”

Embroidered Tablecloth

Embroidered Tablecloth

This tablecloth came to the Carpatho-Rusyn Society from the late Leona Hrehovcik of Little Falls, New Jersey. Her mother, Mary Stilicha Malenich, emigrated from the Carpatho-Rusyn village of Certiz, today in the Transcarpathian Region of Ukraine. Malenich settled in Passaic, New Jersey (a Carpatho-Rusyn immigrant population center) and used this tablecloth on her table every year for Christmas Eve Holy Supper—a tradition in which Carpatho-Rusyn families gather around the table and eat meatless and dairy-free foods, sing carols, and prepare for Christmas. When the Carpatho-Rusyns converted to Christianity, they integrated practices and traditions from a day of ancestor worship celebrated on December 21, the winter solstice, into the Christmas season. One tradition involves blowing on the seat of one’s chair before sitting down to dinner to make certain that no ancestors are already occupying it.

Embroidered Tablecloth: Detail

Embroidered Tablecloth: Detail

Carpatho-Rusyn embroidery spans a range of patterns, from very geometric in the eastern part of the region to very floral in the western part of the region. The village where this tablecloth originated is on the western side of the middle of the region: the embroidery patterns show a mixture of geometric and floral motifs. The lighter pink and red flower basket motifs probably were introduced by people of German origins who settled in the region.

Food, Music, and Art

Baked Loaves of Paska

Baked Loaves of Paska

Paska, a sweetened egg bread decorated with a number of patterns including cross shapes or thorns, is one of several foods that are traditionally included in a Carpatho-Rusyn Easter basket.

Traditional Carpatho-Rusyn Easter basket with Paska

Traditional Carpatho-Rusyn Easter basket with Paska

Carpatho-Rusyns traditionally take their Easter baskets to church to be blessed by the priest before breaking the Lenten fast on Easter day.

Mary Ellen Dudick making Paska based off her mother's recipe

My Mother’s Paska

This paska recipe was developed by Mary Ellen Dudick after her mother’s version, based on her sister-in-law’s recipe. Dudick remembers that her mother began to experiment with that recipe, changing fresh yeast to dry yeast and swapping in different kinds of shortening. Dudick herself began tinkering with the recipe when Rapid Rise dry yeast came on the market, using the microwave to heat the liquid ingredients. She also found that using the right kind of baking pan was the key to a perfect loaf. This recipe is a great example of how the descendants of immigrants work to keep traditions alive by adopting modern methods to achieve traditional results.

Photo taken in 1998 in Krynica, Poland

A Sing-along in the Homeland

This photograph shows Jerry Jumba playing the accordion alongside John Righetti, right, two prominent organizers in the global Carpatho-Rusyn community. Jumba was a cantor at Warhol’s funeral and was instrumental in starting the Carpatho-Rusyn Event and other collaborations at the Andy Warhol Museum. This picture was taken in 1998 in Krynica, Poland during a visit by American Carpatho-Rusyns to their ancestral homeland.

St. Nicholas Icon

St. Nicholas Icon

This icon of Saint Nicholas of Myrna, one of the most widely known saints of the Greek (Byzantine) Catholic Church, dates from approximately 1900. This icon belonged to Christina Duranko of Whitaker, Pennsylvania and was brought from Europe by her grandparents, Maftej (Matthew) and Teodora Duranyk, from Jezupol, Galicia (today in Ukraine). It is believed to have been printed in Germany or Austria. Since St. Nicholas is the patron saint of the Carpatho-Rusyn people, similar prints could be found in almost every Carpatho-Rusyn immigrant household in America, The Duranyks brought this icon with them when they settled in Rankin, PA in 1904. It hung in their home for much of the twentieth century. While most people know him best for his association with gift-giving during the Christmas season, St. Nicholas is also the patron saint of the Byzantine Catholic Church and the Greek Catholic Union. He is known as “the wonderworker” due to the many miracles attributed to him, including saving sailors from a storm at sea and feeding the hungry during a famine.

According to tradition, Nicholas had a vision the night before he was chosen as Archbishop of Myrna. In this vision,Christ the Savior presented him with a Gospel and the Virgin Mary gave him the omophorion, which is the distinguishing vestment of a bishop and the symbol of his spiritual and ecclesiastical authority. This vision is referenced in the painting seen here by the small figures of Christ and Mary depicted on either side of Saint Nicholas. The inscriptions, written in Church Slavonic Cyrillic, say “Jesus Christ” “Mary, Mother of God” and “Nicholas.” Under the figure of Christ, it says “Wonderworker” with an unusual spelling.

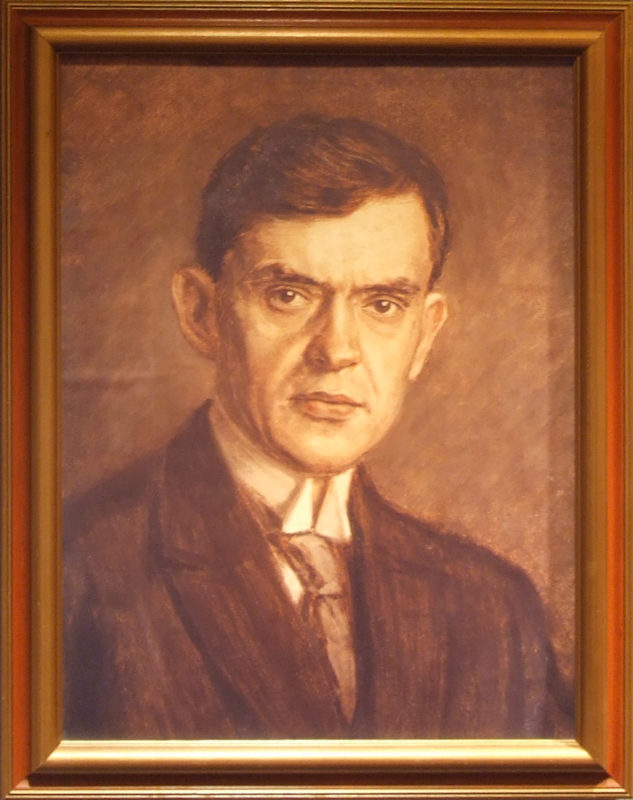

Portrait of Gregory I. Zatkovich

Portrait of Gregory I. Zatkovich

Gregory Zatkovich was born in Holubyne, a Carpatho-Rusyn village in the former Bereg County, currently in Ukraine. His father was the first editor of the leading Carpatho-Rusyn-American newspaper, the Amerikansky Russky Viestnik. He attended the University of Pennsylvania for both his undergraduate and law degrees. He then became a lawyer for General Motors in Pittsburgh. On July 23, 1918, in Homestead, PA, the American National Council of the Uhro-Carpatho-Rusyns formed, and asked Zatkovich to be its spokesman. In negotiations between Czechs, Slovaks, Carpatho-Rusyns, and the US government, Zatkovich pressed for self-determination for his people, creating a place for Carpatho-Rusyns within the newly unified Czechoslovakia. In 1920, he became the first governor of Carpathian Ruthenia, an autonomous province within Czechoslovakia, but resigned within a year due to differences of opinion with the Czechs about the definition of autonomy. Zatkovich then returned to Pittsburgh to focus on his law practice and became the editor of The Carpathian (1941-1943), a journal that advocated a stronger Czechoslovakia comprised of Czechs, Slovaks, and Carpatho-Rusyns in three equal parts. He died in Pittsburgh in 1967 and is buried in Calvary Cemetery in Greenfield, a neighborhood in Pittsburgh’s East End that is still home to many Carpatho-Rusyns.

Family Photos

California Playboys: Andy and Tony

California Playboys: Andy and Tony

This photograph shows Helen Timo’s so-called “playboy uncles”, Tony and Andy, who moved to California in the 1920s.

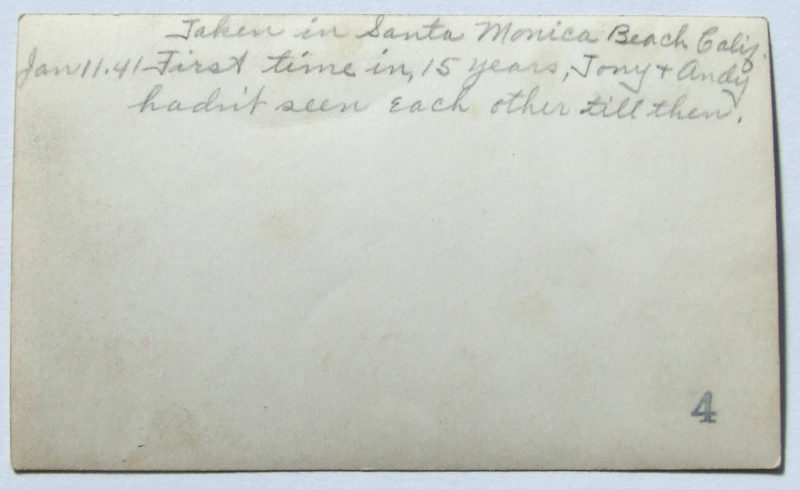

California Playboys: Note on Reverse of Photo

California Playboys: Note on Reverse of Photo

According to a handwritten note on the back of the photo, this was the first time the brothers had seen each other in fifteen years. They are thought never to have married. When one of the uncles died, his nieces and nephews received a small inheritance. The uncles were laid to rest in the family plot in Donora, Pennsylvania. Though the nieces and nephews were not close with their uncles, they felt responsible for giving them a proper burial.

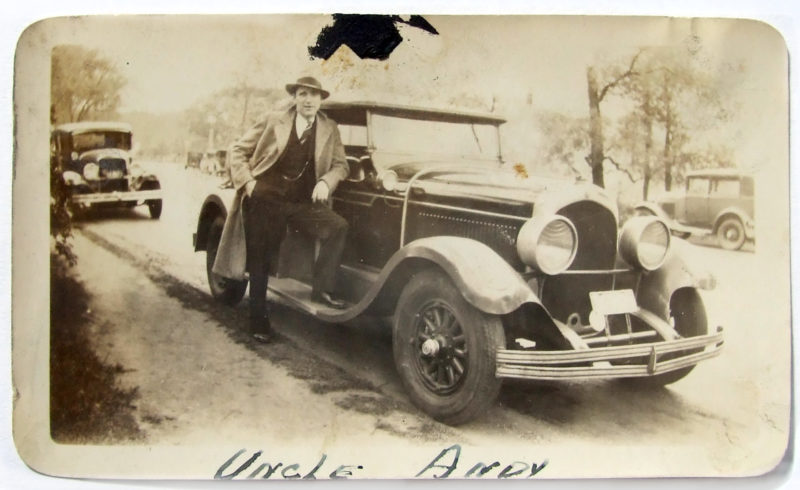

California Playboys: Uncle Andy with Car

California Playboys: Uncle Andy with Car

This photo shows Timo’s Uncle Andy posing proudly with his car, most likely a 1928 Chrysler convertible. Owning a car was a symbol of success and it seems likely that Andy sent this photo back east as proof that he was doing well for himself in the Golden State. Maria Silvestri, Timo’s granddaughter, finds it especially intriguing that these two men left their Carpatho-Rusyn village to come to America, where Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants formed tight-knit communities, but then left that supportive environment to forge yet another path in California. For these young immigrant men, the East Coast was only an intermediate stop in their quest for the American Dream.

Making Rag Rugs with a Loom

Making Rag Rugs with a Loom

These photos show a large loom that Helen Timo and her family would set up in their backyard to make rag rugs. It was probably made by her brother Andrew, who was skilled at woodworking. It’s a very simple model, using pipes set into the ground to hold the warp threads and a wooden heddle to help batten down the rags. Traditionally, the weft is made with rags cut into strips and sewn together into long pieces, but the bottom left shows a rug that was actually made out of plastic Giant Eagle grocery bags. Setting up the loom was a big project that gathered many people together. Friends and family came from far distances to participate, and many rugs would be made in one day. It took two people to work the heddle and it was important that they be physically matched so that the pressure would be equal and the rug would remain square.

Grandmothers Identifying Photographs

Grandmothers Identifying Photographs

Left to right: Mary Hamchak, Marie Scrip, Helen Timo. Mary and Marie were in Helen’s wedding in 1942 and all three women remained close over the years. In this photo, they are working to identify the people in a historic group portrait lest they become anonymous.

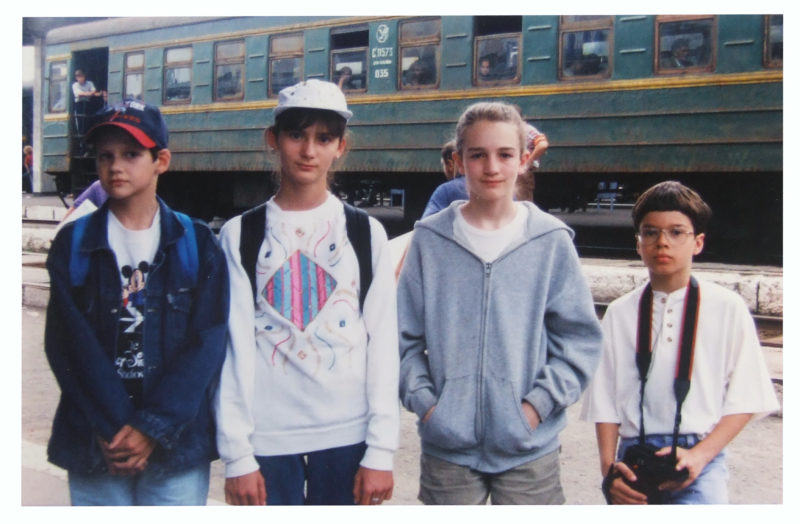

Cousins Meet for the First Time

Cousins Meet for the First Time

This photograph was taken at Station Uzhhorod, near the border between Ukraine and Slovakia. According to Maria Silvestri, this was “the end of the line for what had been the Soviet Union.” This was the first time Silvestri met her European cousins; at this point, they had not yet traveled to the village where the family lived. Though she was quite young, Silvestri remembers having a very strong reaction to the place and her cousins’ lives. She says, “…that was maybe the first point in my life that I was truly confronted with my agency [as an American].” Silvestri believes it could easily have been her branch of the family who stayed in Europe and she can hardly imagine how different her life would have been. Roman and Miroslava’s grandmother was forcibly relocated by the Polish government after the Second World War during Operation Vistula in 1947. Their grandmother, her mother, and grandmother were put into a boxcar and moved east into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. When they were finally let off, they had to make a new life for themselves without the help of any male relatives and with no Ukrainian language. Because of the language learning curve, Roman and Miroslava’s grandmother struggled in school, but her children and grandchildren have adopted their Ukrainian identity.

Family Photo in Donora, Pa

Maria Silvestri estimates that this family photo is from the late 1920s—it was definitely taken at the family home in Donora, a former mill town on the Monongahela River about twenty five miles south of Pittsburgh. The five children are, from left to right: Helen; Nell; Evelyn; Margaret, whom they called Jen; and a friend who was visiting from elsewhere. At the time, several generations lived within a block of each other in Donora, along with friends who shared origins in the same villages.

Tools and Communication

Cyrillic Typewriter: Side View. From the collection of the Greek Catholic Union.

Cyrillic Typewriter

This typewriter was made by LC Smith and Corona Typewriters Inc., and uses the Cyrillic alphabet. Cyrillic is used to write many languages, particularly those of Slavic origin, including Carpatho-Rusyn.

Cyrillic Typewriter: Front View. From the collection of the Greek Catholic Union.

Cyrillic Typewriter

The typewriter dates from the early twentieth century, when it was used to write stories and articles for the Amerikansky Russky Viestnik, a Carpatho-Rusyn newspaper published by the Greek Catholic Union.

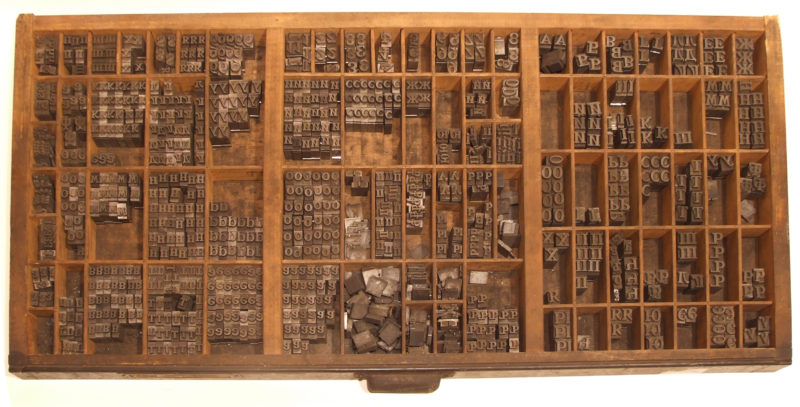

Cyrillic Type. From the collection of the Greek Catholic Union.

Cyrillic Type

This box is filled with type representing the upper and lower case letters of the Cyrillic alphabet, which is used to write the Carpatho-Rusyn language. Until the mid-twentieth century, type like this had to be set manually—and backwards—to spell out the words to be printed in newspapers, magazines, advertisements, and other print media. This type was used to print the Greek Catholic Union newspaper, Amerikansky Russky Viestnik.

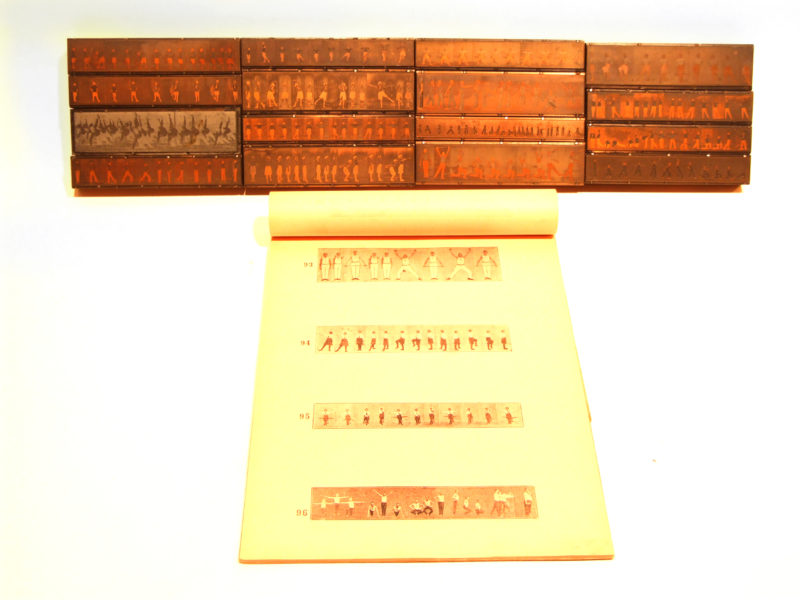

Letterpress Blocks and Printed Images. From the collection of the Greek Catholic Union.

Letterpress Blocks for Gymnastics Manual

These letterpress blocks, made of copper and wood, were used to print the photos for the American Rusin Sokols’ [sic] gymnastics manual, circa 1920. Based on Slovakian founder Dr. Miroslav Tyrs’ credo of “A Sound Mind in a Sound Body,” Sokols (from the Slavic word for falcon) were organizations for Czechs, Slovaks, and Carpatho-Rusyns that provided a space for physical education and social interaction. The first Sokol was founded in 1862 in Prague. Immigrants to the US brought the ideals and structure of the organization with them. In1865, the first American chapter was founded in St. Louis. In 1879, the American Sokol held its first athletic competition, known as a Slet. Individual Sokol units (also known as clubs) from around the country sent competitors to Slets in hopes of bringing home a prize. Membership in the American Sokol movement continued to grow through the middle of the twentieth century, with 2,253 people participating in the Slet of 1961. Participation fell as other options for physical activity became widespread. Today, there are thirty five units/clubs operating in North America, including one in the South Side of Pittsburgh. The South Side Sokol continues to offer gymnastics classes and other athletic activities, but also functions as a bingo hall and wedding venue.

Records, News, and Events

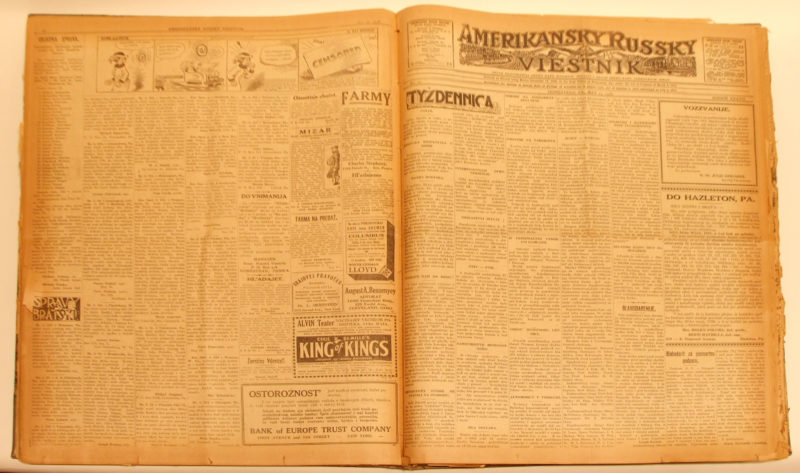

Amerikansky Russky Viestnik Newspaper

Amerikansky Russky Viestnik Newspaper

This was the leading Carpatho-Rusyn-American newspaper in the first half of the twentieth century and was the official publication of the Greek Catholic Union of Carpatho-Rusyn Brotherhoods. It was founded in 1892 by Paul Zatkovich, whose son Gregory Zatkovich would later play an important role in the political quest for Carpatho-Rusyn autonomy during the first Czechoslovak Republic. At its height in the 1920s, the Amerikansky Russky Viestnik (which translates as the American Rusyn Messenger) appeared three times weekly and had a circulation of 100,000 copies. The paper was published in the Carpatho-Rusyn language in two versions: one used the Cyrillic alphabet, which is used to write many Slavic languages including Russian and Carpatho-Rusyn; the other used the Roman alphabet—still in Carpatho-Rusyn but transliterated. By 1952 it was replaced with the English-language Greek Catholic Union Messenger, which ran until 1992. Today, it survives as GCU Magazine.

GCU Magazine. From the collection of the Greek Catholic Union

GCU (Greek Catholic Union ) Magazine

This is the current incarnation of the Greek Catholic Union’s publication, an example of Carpatho-Rusyn media from Western Pennsylvania. The GCU Magazine is published six times a year by the GCU to highlight its member’s accomplishments and the benevolent work done by the organization’s lodges throughout the country.

Group Portrait of 1st Greek Catholic Union Convention

Group Portrait of 1st Greek Catholic Union (GCU) Convention

This is a photograph of lodge delegates attending the first Greek Catholic Union of Carpatho-Rusyn Brotherhoods (GCU) convention in 1893, one year after its founding. The President, John Zinchak Smith, is standing center front wearing a top hat. Fraternal organizations like the GCU were a way to display ethnic pride and provide services to the community. Membership dues helped provide a modest income to those who had been laid off or injured, and could also be used to cover funeral costs. These organizations also provided a haven of Carpatho-Rusyn culture and language, hosting dances and banquets as well as organizing youth sports activities. During the early twentieth century, the GCU was politically active in the matter of uniting the Carpatho-Rusyn territory with Czechoslovakia when it was founded in 1918. Today, the GCU offers its members life insurance and annuities and owns Seven Oaks Country Club in Beaver, Pennsylvania, but also continues to promote Carpatho-Rusyn culture in America.

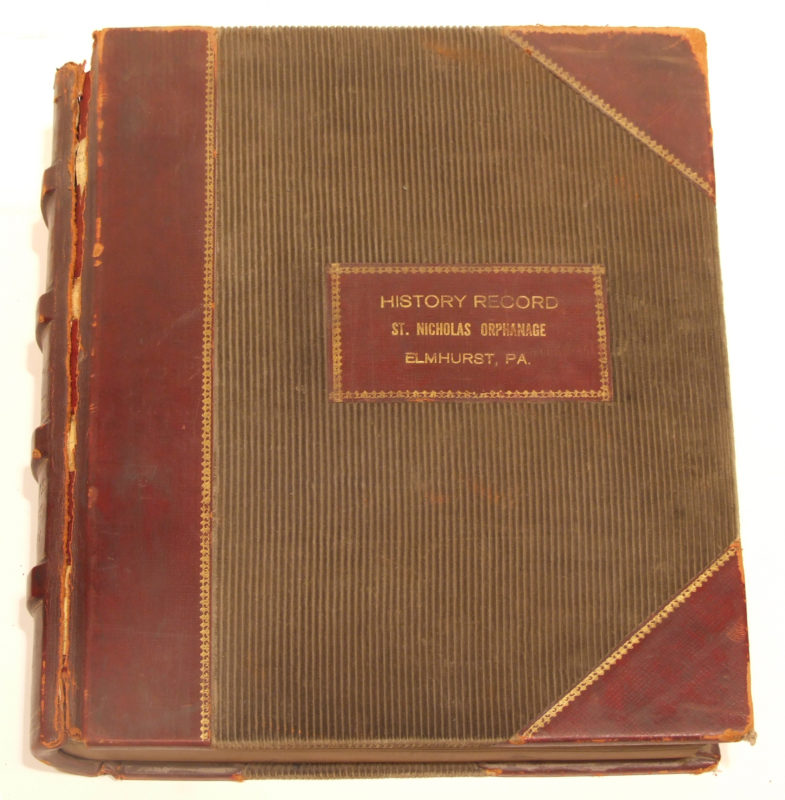

History Record of St. Nicholas Orphanage, from the collection of the Greek Catholic Union

History Record of the St. Nicholas Orphanage

This book is from the collection of the Greek Catholic Union and contains records of all orphans who were housed at the St. Nicholas Orphanage in Elmhurst, Pennsylvania during the first half of the twentieth century. The orphanage was heavily supported by the Greek Catholic Union and was staffed by the sisters of the Order of St. Basil the Great beginning in 1923. It was named after the patron saint of the Greek Catholic Union, Saint Nicholas, who is known as the protector of children in addition to his gift-giving role during the Christmas season.