The recent passing of this great American artist calls to my mind a wonderful memory of him, and the fragment of a memory, which he generously shared with me. For a few days in October 1997, I was busy working in the imposing edifice of Haus der Kunst (literally, the “House of Art”), in Munich to pack-up Warhol’s Time Capsule 472 in the extraordinary exhibition Deep Storage: Arsenals of Memory, co-curated by Ingrid Schaffner, who since then (and even before, of course), has organized many wonderful and intelligent exhibitions (a few of which she asked to borrow from the museum’s collection, which I was SO happy to do). She’s become a very dear and delightful friend and colleague, and I can’t wait to see how her brilliance is revealed in her role as the curator of the next Carnegie International, scheduled to occur in Pittsburgh in 2018. With her track record, Ingrid’s show promises to be extremely exciting!

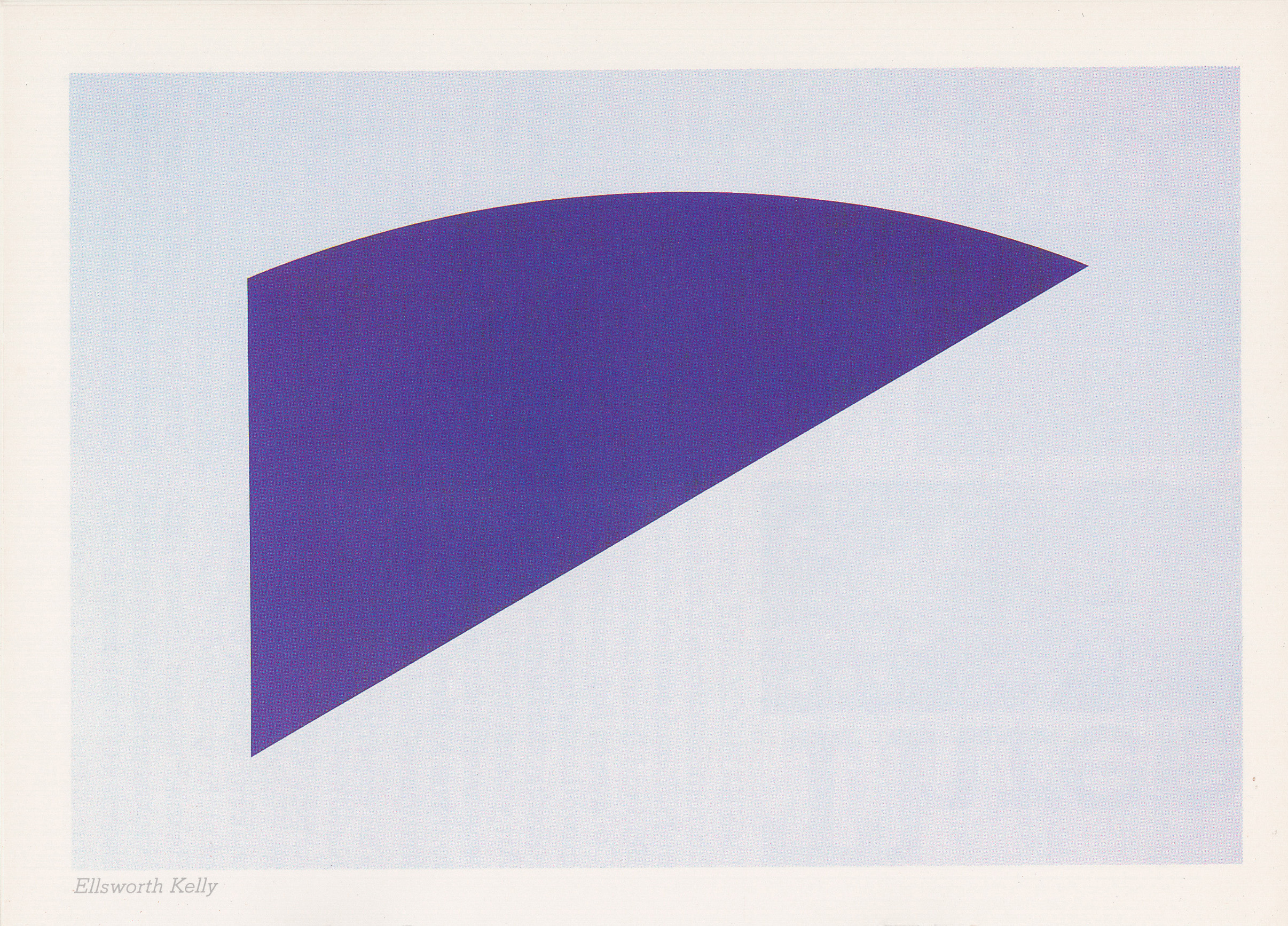

Meanwhile, back in Munich, during a lunch break I met a young man who was the assistant of artist Ellsworth Kelly; they were installing the next show at Haus der Kunst: a full-on retrospective of Mr. Kelly’s beautiful abstract paintings and sculpture. This news was a great surprise, as Mr. Kelly’s work was of great interest to me when I was a young art student in the 1970s, and I was enthralled by the bold freedom expressed in his work.

I mentioned this to the assistant (whose name I do not recall, regrettably foreshadowing in retrospect, as it were). He replied that I should tell this personally to Mr. Kelly (or, as he put it, “You should tell Ellsworth; he would be so happy.”) I was in total astonishment; imagine having the chance to speak to one of the heroes of your youth. We decided that the assistant would relay this to his boss. The next day, still to my surprise, I was invited to have a coffee.

I could not hide my shyness, but I managed to utter my story, to say how just seeing a group of his then-new curvy shaped canvases from the mid-1970s reproduced at a mere fraction of their actual size in a catalogue for a show at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., changed my ideas about what art could be, and how much I admired his boldness and the importance of that experience for my efforts at painting in art school. Mr. Kelly was indeed very happy to hear this; I was taken aback, again. As he was a huge art star, I assumed that he would be accustomed to such stories and that another would make no difference, but his personality was equally as graceful as his elegant art work.

Mr. Kelly noted my position, and elaborated; it went something like this: “So, you work for The Andy Warhol Museum. I knew Andy, and I recall a story that you may want to hear. It’s not much, just a fragment, but I think it shows a side of him that many people aren’t aware of.”

Wow, I thought, what could this be? “Yes! Please, what do you remember?” I almost fell off my stool; this was a golden opportunity. It’s so important to collect memories before they are gone!

After apologizing for not having all of the details, Mr. Kelly then told me the tiny fragment of memory that he had: sometime in the 1960s or ‘70s, at a sale or auction of contemporary art, several of the artists were walking through the exhibition of works. One—a young woman—was upset with the manner in which her work was displayed; she felt that it was not being shown to its best advantage, and Warhol was adamant in telling her to insist that the work be re-hung to her satisfaction, as this would affect the sale price, and subsequently would lower her prices forever after.

Mr. Kelly could not remember the artist’s name, or what her work was like, so we could not even guess who it might have been. But, as he said, her identity wasn’t so important, it was what HE did. Mr. Kelly emphasized: Andy Warhol gave free career advice to another artist—not being competitive, but supportive.

And she (that mysterious unnamed artist), did become a very well-known and successful artist, “You know her, and her work, I just can’t remember her name, I’m so sorry!” is something like how he put it, as I recall now, nearly 20 years later.

And of course, Mr. Kelly was right; Warhol had such a public visibility as a celebrity far beyond the art world, that for him to make the effort to point out the seriousness of that crucial moment to the artist, it would seem quite surprising to people who did not know him well, and even for those (such as Mr. Kelly), it was an extraordinary moment of generosity.

So, as we have just passed the holiday season, also known to many as the “Season of Giving,” it seems appropriate to bring this memory of “giving of oneself” by the museum’s namesake and subject: Mr. Andy Warhol, who gave the world so very much.

As did Mr. Ellsworth Kelly: he gave me a beautiful (if brief, and even frustrating), memory that I am delighted to share with the readers of this blog. He inspired me to create in my youth, and his enormous output of art is still very exciting to me and to many others. Just like Warhol, Mr. Kelly was a true master, a giant of his time, and for all time.