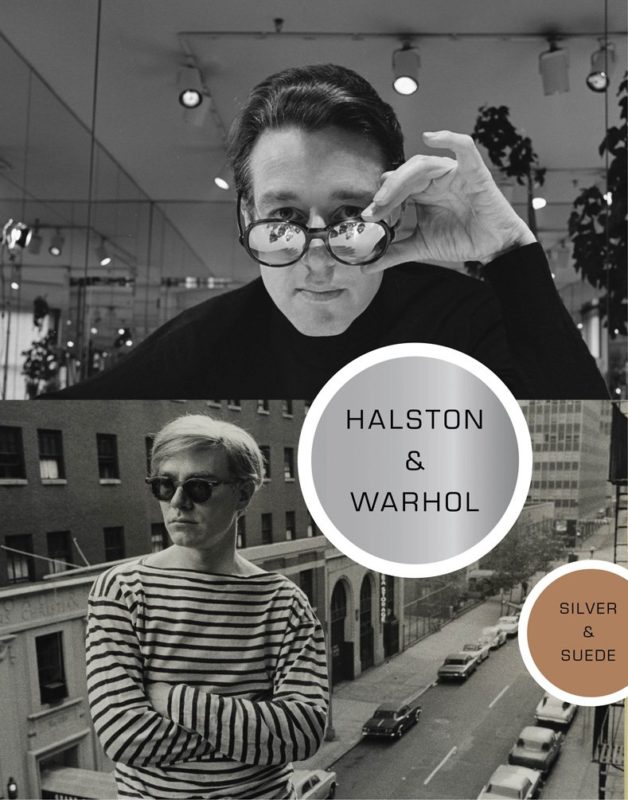

The exhibition Halston and Warhol: Silver and Suede examines the interconnected lives and creative practices of Andy Warhol and Halston - two American icons who had a profound impact on the development of 20th century art and fashion.

Halston and Warhol: Silver and Suede

May 18 – August 24, 2014

The Pillbox Hat

Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis (1929–1994) rose to prominence as the wife of President John F. Kennedy but soon demonstrated her own talents as hostess, style icon, mother, and arbiter of good taste. In her role as First Lady she was admired internationally for embodying elegance, and in the world of fashion she became a trendsetter who influenced designers, magazine editors, and the public at large.

Halston’s profile in American fashion was immediately elevated when Jackie asked him to design her hat for the inauguration day celebrations in 1961. His pale pink pillbox hat was seen by millions as Jackie’s image was broadcast on television and circulated in print.

Deeply affected by the assassination of President Kennedy in November 1963, Warhol began a series of portraits of the widow. Based on eight different reproductions from newspapers and magazines, these portraits were shown individually and in groups. The shifting images created a cinematic effect and transformed the historical narrative into a series of affecting moments. The initial exhibition of the Jackies, which entailed a single profile image repeated 42 times, occurred at the Leo Castelli Gallery almost one year after the assassination.

Even long after the event, Warhol was amazed at the power that the image held: “As we walked through the galleries every person recognized Jackie. They didn’t come too close. They stopped for a minute, looked, and whispered. You could hear her name in the air: ‘Jackie. Jackie.’ It’s a very strange feeling. There is so much awe and respect for her. Being with her is like walking with a saint.”

Ultrasuede

Halston intuitively understood the properties of both natural and man-made fabrics and used them equally well to define a new silhouette for the American woman. He ignored the traditional hierarchy of material, selecting rare six-ply cashmere or fine leather for casual separates and employing utilitarian synthetics, such as rayon matte jersey, for evening dresses, all with the same luxe results.

Ultrasuede has become synonymous with the designer due, in part, to his famed design of the classic shirtdress model No. 704 (78,000 copies of which were sold after its debut in the fall of 1972). In 1970 a Japanese company, Toray Industries, first developed the synthetic microfiber and sold it under the name Ecsaine. Toray gave samples to a number of designers including Issey Miyake, who then showed it to Halston.

As soft as suede, stain resistant, seemingly impervious to wrinkles, and machine washable, the fabric was a wonder for Halston. Mistakenly thinking the material (a combination of polyurethane and polyester) was water resistant, Halston first created an Ultrasuede raincoat for his spring collection in 1971. The incredibly popular shirtdress was designed months later. Women no longer cared if they arrived to a party wearing the same outfit; everyone wanted this versatile dress that could be packed in a suitcase and worn to either lunch or dinner. It looked luxurious but was inexpensive to care for.

The ultra-microfiber that came in many colors found its way into Halston’s designs for both men’s and women’s suits, evening wear, Braniff International Airways uniforms, bedspreads, and luggage sets.

Collaboration

Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, Halston and Warhol developed a close friendship and professional relationship that resulted in collaborations, commissions and projects inspired by each other’s work. They opened up a dialogue across the fields of art, design, and fashion that was pioneering for the time and continues to exert considerable influence on contemporary culture.

Their first collaboration occurred in 1972 when Warhol was invited to create Halston’s runway presentation for the Coty Awards. Billed as “An Onstage Happening by Andy Warhol,” the performance brought Halston models (later termed “Halstonettes”) and Warhol “Superstars” together in a bizarre spectacle that Warhol also captured on video. The intermingling of their respective milieus continued the following year when Halston models Pat Cleveland, Nancy North, and Karen Bjornson were cast in Warhol’s experimental soap opera Vivian’s Girls.

In 1974, Halston commissioned Warhol to paint his portrait and also created an evening dress with a print derived from Warhol’s iconic Flowers paintings. Other notable projects included Warhol’s first foray into broadcast television, Fashion, 1979, which featured an episode devoted to Halston, and Warhol’s 1982 advertising campaign for Halston menswear, accessories, and cosmetics.

As documented in Warhol’s 1980 book Exposures, which included a chapter on Halston, the artist’s and designer’s interconnected social lives provided a platform that fostered intersections between the worlds of art and fashion.

Halston DNA

The casual elegance of Halston’s designs helped to define a new American style and revolutionize fashion in the 1970s. His understated, comfortable clothes were a departure from the conservative, heavily tailored forms of the 1950s and the disheveled, hippie look of the 1960s. Clean lines and luxurious fabrics became his signature.

A connoisseur of traditional haute-couture dressmaking techniques, Halston developed fresh new designs based on both Western and non-Western forms. His elongated cardigan with coordinating sheath was drawn from the classic 1950s twinset; his Ultrasuede shirtwaist dress was based on a man’s collared shirt; his caftans in diaphanous silk chiffon were translated from Near Eastern clothing; and his narrow column of fabric tied at the bust echoed the drape of Grecian robes. Halston transformed the staple of every man’s wardrobe, the tailored business suit, into a relaxed pantsuit for women. Even pajamas, traditionally not worn outside the home, were refashioned into elegant eveningwear.

These garments appeared deceptively simple. In fact, the construction often em-ployed complicated folding, draping, and cutting. Fit and comfort were paramount to Halston. He was famous for shifting the attention away from the look of a piece to the way it felt on the body and was known to run a swath of fabric along his cheek to ensure it had just the right softness.

Perhaps most important, Halston’s charm and genuine appreciation for the women he dressed engendered lasting friendships with clients. Like Warhol, Halston recognized the power of personality: “Women make fashion. Designers suggest, but it’s what women do with the clothes that does the trick.” As his career advanced so did his association with the glamorous elite, including Warhol’s friends and clients Elizabeth Taylor, Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli, and starlet-models Pat Cleveland and Marisa Berenson.

Class to Mass

By the 1980s, Halston’s casual elegance had become a sought-after brand. His business was growing and with that success came licensing agreements for ready-to-wear designs. In 1982 Halston struck an unprecedented deal to market his brand with the American retailer J.C. Penney, which he saw as a way to bring sophisticated design to the heartland. “What I always wanted to do was dress America,’’ he professed, “and being a dreamer, a romantic, in a way, I thought, ‘What a wonderful idea.’”

The deal, although common today, was received with great skepticism and caustic criticism by the fashion elite. Bergdorf Goodman, the store that had carried his label for 20 years, announced that it would no longer sell Halston clothes and fragrances, fearing that J.C. Penney had diluted his cachet.

In the late 1970s, Warhol also became the target of unfavorable criticism due, in part, to initiatives like Interview magazine, which broadened his appeal beyond the art world. His 1979 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art was famously panned in Time magazine by Robert Hughes: “Warhol’s admirers, who include David Whitney, the show’s organizer, are given to claiming that Warhol has ‘revived’ the social portrait as a form. It would be nearer the truth to say that he zipped it into a Halston, painted its eyelids and propped it up in the back of a limo, where it moves but cannot speak….” Warhol’s pithy response to the review: “They gave me two whole pages. With three photographs. In color.”

Studio 54

In April 1977, Studio 54 opened its doors and quickly became the playground for the rich, beautiful, young, and undiscovered of New York. High society mingled with low on its dance floors. In Warhol’s words, “It was a dictatorship at the door and a democracy on the floor,” and the challenge of gaining admission and making it past the infamous velvet rope, was part of its appeal.

Warhol became a regular at the nightclub—his presence there brought him fame in the tabloids and gossip columns, making his name synonymous with the New York nightlife. Halston was also often found in the VIP section with Liza Minnelli and Bianca Jagger, two of his regular clients. A week after the nightclub’s opening, Halston arranged a private party to celebrate Bianca Jagger’s birthday. While only a few photographers were allowed access to the event, images of Bianca’s dramatic entrance on a white horse were leaked to the press, and Studio 54 was an instant sensation.

Before the flash of the paparazzi bulbs could ruin the careers of celebrities, at a time when AIDS was not yet diagnosed, Studio 54 captured an uninhibited period of freedom and experimentation in the 1970s.

Miss Piggy

During the summer of 1984, the Muppet’s Miss Piggy was featured on Entertainment Tonight shopping for a wedding dress from Halston’s Resort Collection. While the segment was made without Halston’s participation, he was flattered when he saw the clip and decided to write a letter to Miss Piggy and Kermit the Frog, congratulating them on their nuptials. Halston offered Kermit a selection of his licensed grooming products. In return, Muppets creator Jim Henson sent a box full of Muppets memorabilia.

It was a timely offering, very close to Warhol’s birthday, and Halston gave all the Muppets collectibles to Andy as a gift, signing each one: “To Andy Happy Birthday love Halston.” Warhol saved all of the items in a Time Capsule, the complete contents of which are on view for this exhibition.

Martha Graham

Martha Graham (1894-1991), like Warhol, was born in Pittsburgh. She went on to become one of the greatest pioneers in modern dance in the twentieth century. Graham developed a distinctive style that critics at first called “ugly” dancing. She experimented with the body’s natural movements, contraction/release and tension/relaxation. Influential and unafraid to cross genres, Graham collaborated with artists, designers, and musicians, including Isamu Noguchi, Warhol, Halston, Donna Karan, Calvin Klein, Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, and Gian Carlo Menotti.

When Halston met Graham in the 1970s, the dance company she had founded a half-century earlier was faltering financially. Halston became an important patron, designing outfits for Graham’s personal use and costumes for her troupe at no charge. They shared a keen understanding of the human form. Utilizing some of the same body-conscious textiles he employed for his couture and ready-to-wear lines, Halston produced costumes for many of her ballets, including “Clytemnestra,” “Frescoes,” and “Episodes.”

Warhol first saw Graham’s troupe perform in Pittsburgh in 1948. At the time he was obsessed with modern dance, and in college was the only male member of the modern dance club. Three decades later, Warhol painted Graham’s portrait and also produced a print series of her dancers to be auctioned at a benefit for her company. From the mid-1970s through the 1980s, Halston, Graham, and Warhol supported each other’s activities in art, dance, and design.

Olympic Tower

In January 1978 Halston moved his Manhattan office, workroom, and showroom from the 68th Street studios to the new Olympic Tower building at 51st Street and Fifth Avenue. Dubbed the “OT” by Halston and staff, the new space provided a 12,000-square-foot workroom complete with dozens of new sewing machines.

Halston created a total environment. All of the walls were covered with mirrors. The main space was engineered with 18-foot movable partitions that created smaller rooms or could be folded back to open up a great room for a runway show with seating for 300. The view from the 22nd floor through the floor-to-ceiling windows framed the magnificent spires of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and midtown Manhattan beyond.

The décor was modern with minimal furniture. Red-lacquered Parsons tables served multiple purposes, including as a desk for Halston. A continuous supply of orchids and Elsa Peretti silver candlesticks were among the few decorative objects in the bold and elegant space. Warhol suggested the vibrant red color for the carpeting that lined the entire floor and was embossed with Halston’s signature initial H.

Victor Hugo

Halston met Victor Hugo in early 1972. Both were avid fans of Pop Art and Dada, and mingled in social circles with fellow artists, Warhol, Larry Rivers, Louise Nevelson, and Arman. Halston and Victor became romantic partners, and, eventually, Halston pulled Victor into his fold and hired him to design his Madison Avenue boutique windows. Hugo produced inspiring but controversial windows; taking great pride in his work, he stated, “I put windows on the map as a Pop artist. I looked at it as art. The windows became my paintings, my occupation.” Halston created dresses that would never go out of style, but Victor’s edgy windows gave the label contemporary street cred.

Hugo was also a close associate of Warhol. In 1975, he “carpeted” Halston’s window display with copies of Warhol’s book THE Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again). A regular visitor to Warhol’s studio in the late 1970s, Hugo modeled for Warhol’s Torso and Sex Parts series and also collaborated in the production of the Oxidation paintings.

Publication

Halston & Warhol: Silver & Suede

Halston and Warhol illuminate through their art and fashion a uniquely American point of view, one that matched high and low materials and deceptively simple forms with multistep processes. Both were outsiders, one from Pittsburgh and one from Iowa, whose New York careers challenged the status quo. For the first time, their lives and work are presented side by side in over 300 images with interviews and essays that explore their friendship and their art.

The Andy Warhol Museum, Lesley Frowick, Geralyn Huxley, and Valerie Steele

Hardcover, 240 pages, 310 illustrations

Publisher: Abrams, 2014

$50