When he entered the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) as a freshman in 1945, Andrew Warhola embarked on the formal road to what would become one of the most celebrated art careers of the 20th-century.

With America embroiled in the final throes of World War II and the steel mills and factories of Pittsburgh churning out heavy materials at full tilt, the rarefied world of the academy (with classes taught by artists Balcomb Greene, Robert Lepper, Samuel Rosenberg, and Howard Worner, among others) would have been a comforting realm within which the future Andy Warhol (he dropped the final “a” in the 1950s to make his name seem less ethnic) could develop his aesthetic voice. The day before he entered college, Warhol sat for a portrait photo in a small photo studio operated by his middle brother, John, and their cousin Johnny Preksta. Interestingly enough, in relation to Warhol’s yet-to-come work of the early-1960s, it consisted of a photobooth machine, and the customers received not just the black-and-white product, but a hand-colored portrait. However, in 1945 and ‘46 Warhol struggled with his first-year classes in the Department of Painting and Design., resulting in him having to take a summer drawing class so that he could refine his draftsmanship to please his professors.

The drawings made in the summer of 1946 are technically mature images of women buying fruits and vegetables on the streets of Warhol’s childhood neighborhood of South Oakland, mere blocks away from Carnegie Tech. Warhol spent many days that summer observing his oldest brother, Paul, who sold produce from a truck, and the resultant pictures that he made of those commercial transactions won Warhol accolades upon his return to school in the fall when he received the Martin B. Leisser Prize and had the works exhibited in the college’s fine arts gallery. From that point forward, Warhol was a star student in the program and, over the course of his entire college career, learned all of the many skills that a successful commercial illustrator would be expected to know in the job market.

While at Carnegie Tech, Warhol became involved in various student activities, including the Modern Dance Club (he was the only male in the group) and the Beaux Arts Society. He worked as an editor of the student publication Cano, designing a cover for the magazine in November 1948. His artistic experimentations in 1947 and 1948 led him to develop what would one day become his signature drawing style—the blotted line technique—in which he would ink an image in reverse on a vellum-like paper and then tamp it down onto a clean sheet of paper, resulting in a drippy and imperfect line that was slightly reminiscent of artist Ben Shahn, but still highly unique and playful. In the summer between his sophomore and junior years, Warhol took a summer job in the display department of Horne’s Department Store in downtown Pittsburgh where he continued to hone his skills of selling products through visual enticement.

Warhol’s involvement with the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh—a group of regional artists now celebrating its 100th-anniversary—was both positive and negative to the young artist. In 1948, two of Warhol’s works were selected for inclusion in the AAP’s annual juried show, a painting titled I Like Dance and a print titled Dance in Black and White. The titles alone show Warhol’s great interest in dance—and in fact he once said that he would rather have been a ballerina than an artist—but unfortunately, his fellow members of the Modern Dance Club thought that Warhol’s skills would best be utilized in designing the group’s programs in lieu of him actually taking to the stage. His important Dance Diagram paintings from the early 1960s would ultimately find their inspiration in Warhol’s early forays into the subject.

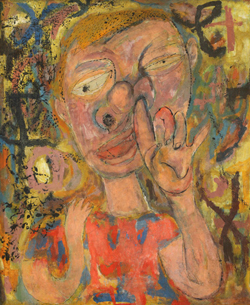

The following year, Warhol tasted the thrill of aesthetic controversy when he was rejected from the 1949 AAP juried exhibition after submitting his The Broad Gave Me My Face, But I Can Pick My Own Nose painting at the beginning of his last semester of his senior year. Featuring a young man gingerly picking his nose, the facial details of the painting suggest that it’s a self-portrait of Warhol, no doubt thumbing his nose at the establishment as he would do throughout his lifetime. The jury declined to accept the work over the protests of juror George Grosz, the elderly German artist who was known for his caricatures of society.

By his graduation in June 1949, Warhol changed the name of the painting to Don’t Pick on Me and submitted it to a student exhibition, where it attracted considerable attention. Recently, several of Warhol’s classmates have recalled that the painting was originally titled “The Lord Gave Me My Face, But I Can Pick My Own Nose,” and it somehow was twisted into the more audacious meaning with the word “broad.”

Within weeks of graduating from Carnegie Tech, Warhol and fellow classmate Phillip Pearlstein departed Pittsburgh and moved to New York City, where over the course of their decades-long careers, both would rise to the upper echelons of the art world establishment. Warhol’s formative years soaking in the art of commercial illustration would indeed serve him well, first as the most celebrated graphic artist of the 1950s and later on as one of the pioneers of the Pop Art movement of the early 1960s.

L2010.2.1Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)Nosepicker I: Why Pick on Me (originally titled The Lord Gave Me My Face but I Can Pick My Own Nose), 1948Tempera on boardThe Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Museum Loan, Paul Warhola Family© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.