Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei explores the significant influence of these two artists on modern and contemporary life.

Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei

June 4 – September 11, 2016

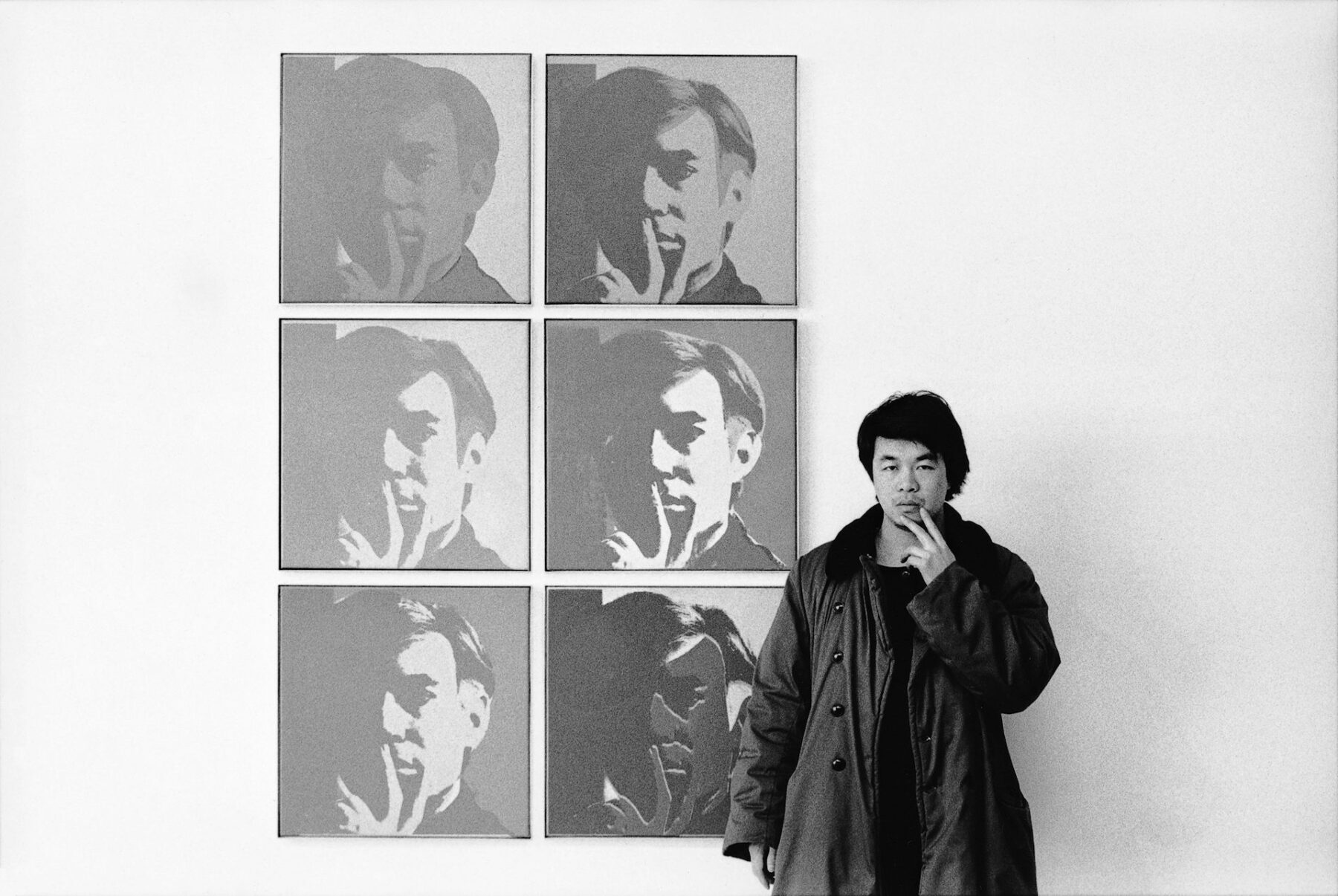

Ai Weiwei, At the Museum of Modern Art, 1987, from the New York Photographs series 1983–93, collection of Ai Weiwei, © Ai Weiwei; Andy Warhol artwork © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Capitalism and Communism

Andy Warhol took a critical look at the American way of life, which had embraced a mix of new capitalism and consumerism after World War II. Warhol borrowed images from popular visual culture and mass media such as advertisements and comics, incorporating logos and products into his work, most notably Coca-Cola and Campbell’s Soup.

When Ai Weiwei returned from the U.S. to China in 1993, he began to look at Chinese art with a critical eye and became intrigued by the various forms, colors, designs, and scripts employed by Chinese dynasties. His first work arising from this interest was Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo, 1994, though the script he refers to is not from ancient China but from the Coca-Cola logo—a symbol of America’s mass consumer society of the 1960s.

Readymade

Marcel Duchamp’s invention of the readymade—an everyday object designated as art by the artist or by its gallery context—is among the most significant influences in twentieth-century art. The art of both Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei helped to spur the reappraisal of Duchamp’s work in New York in the 1960s and again in Beijing in the 1990s.

Duchamp himself appears in Warhol’s Screen Test: Marcel Duchamp, 1966, and in Ai’s Hanging Man, 1985/2009, in which the French artist’s profile is fashioned from a coat hanger.

Social Disease

Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei share an interest in street scenes, intimate moments with friends, and glimpses of society unadorned and exposed. Warhol’s photographic activity accelerated in the second half of the 1970s. By this time, Warhol was producing hundreds of commissioned portraits of celebrities, socialites, and friends. These celebrity portraits showcase Warhol’s stylistic diversity, sense of color, and understanding of fame.

Having left China for America in the early 1980s, Ai was exposed to—and took snapshots of—some of the most dynamic activist movements for civil rights in the U.S., particularly on the streets of New York, which helped to strengthen his belief in individual freedom and social justice.

Surveillance and the State

Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei were both under government surveillance at points during their lives. The FBI began watching Warhol in the late 1960s, after he was suspected of producing and transporting obscene material—namely his art films. Ai endured years of surveillance by the Chinese government, which became public in 2011 when he was arrested and subjected to various forms of interrogation tactics. Throughout his imprisonment and his house arrest, he employed Instagram and other media to expose the surveillance. Ai was detained without charge for eighty-one days in 2011, and he regained his right to travel in July 2015, when his passport was reinstated.

Both artists created images of Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong. Warhol appropriated the subject matter of totalitarian propaganda to create his Pop portraits, addressing the cult of personality surrounding Mao. Ai’s large-scale, hand-painted images of Mao provide a deadpan critique of official state imagery. In Ai’s representations of Mao, he draws on distortions of his image taken from television screens.

Cats

Both Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei lived with an abundance of cats. Warhol is alleged to have had as many as 25 cats in his home at once, and it is reported that 40 cats frequent Ai’s studio in Beijing. Cats are a recurrent subject for both artists, noted in Warhol’s early career blotted-line drawings and photography, and cats are the subject of numerous postings to Ai’s social media feeds and appear in videos filmed at the studio.

Learn more about the role cats play in both artists’ practices on our blog. The essay “Meeooaaww-AW-AWW” by Matt Wrbican, The Warhol’s chief archivist, originally appeared in the exhibition catalogue Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei.

Political Beauty

For Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei, flowers are used to communicate powerful and political messages. In Ai’s work, the flower symbolizes his personal struggles with government oppression. Warhol’s flowers symbolize a provocative gesture flouting the high- and low-value system imposed by the art world.

Warhol produced his iconic Flowers paintings in different sizes, from miniature to monumental, and when he displayed them in Paris in 1965, he covered the walls with 100 canvases, some hung edge-to-edge to mimic the effect of wallpaper. This mass production of paintings, treated as pure decoration, challenged the notions of value and uniqueness in a work of art. Every morning for 600 days between 2013 and 2015, Ai placed a bouquet of fresh flowers at his studio gate to protest the Chinese government’s travel restrictions placed on him. He documented them on Instagram using the hashtag #FlowersForFreedom and encouraged people to share the images, creating a symbol for social activism.

Ai Weiwei's Screen Test

Publication

Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei

A collaborative project between National Gallery of Victoria, The Andy Warhol Museum, and Ai Weiwei, this volume is the first to explore the significant influence of Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei on art, life, and politics, focusing on the parallels and intersections between their practices. It was created to accompany the exhibition Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei.

Max Delany and Eric Shiner, editors

328 Pages, 200+ Illustrations

Publisher: Yale University Press, 2016

Out of Print