Time Capsule 21:

Artwork

Time Capsule 21 is striking in the large amount of Andy Warhol’s art and source material it contains from the 1950s and 1960s. There are three hand-colored prints of shoes from his self-published promotional portfolio titled A la Recherche du Shoe Perdue. There are also 204 individual photobooth strips, magazines, and several album covers created by Andy Warhol. Source material for Warhol’s art includes: photographs of Yoyo Bischofberger, Ethel Scull, actor Tom Courtenay, filmmakers Marie Menken and Willard Maas; a paint-by-number still life of a violin and apples; and the original newspaper headline for his artwork 129 Die in Jet!

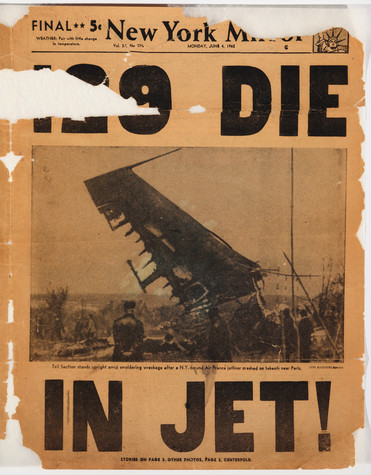

129 Die In Jet!

Newspaper headline ("129 Die in Jet," New York Mirror, June 4, 1962)

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.1

TC21 Object: Newspaper headline "129 Die in Jet," from New York Mirror, June 4, 1962

Andy Warhol was an avid newspaper reader. Blazoned headlines, quirky stories, celebrity gossip, comics, and gory details all captured his attention. The Time Capsules often feature assorted newspaper clippings that intrigued him. Many of these highlight bizarre deaths, freak accidents, or crimes committed by ordinary people. In this particular newspaper clipping from the June 4th, 1962 New York Mirror, the headline reads “129 Die in Jet!” and includes a large image of the crash. Warhol collected and used newspapers, especially the front pages, to model and inform some of his most important works of art.

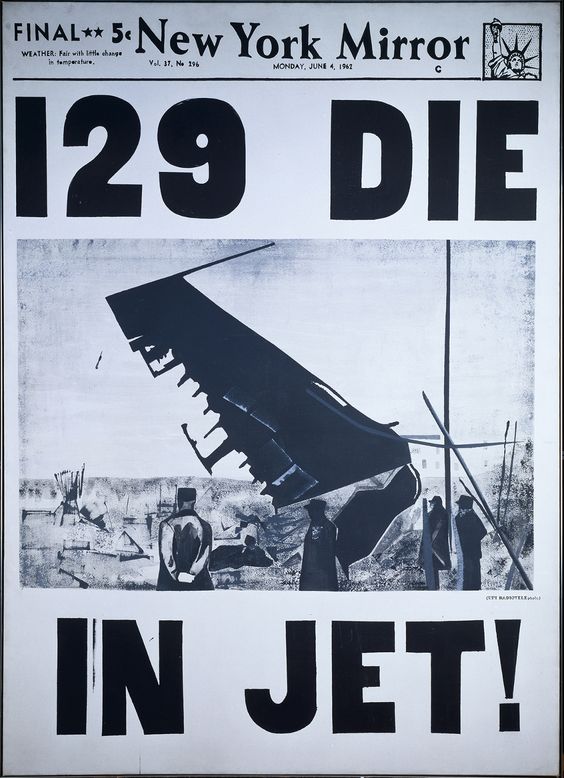

Andy Warhol, 129 Die in Jet, 1962, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © 2011 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, 129 Die in Jet, 1962

This painting builds upon the New York Mirror’s coverage of a plane crash at Orly Airport in Paris in 1962. Warhol enlarges the already imposing headline and photograph of the tattered wreckage on a massive 100-by 72-inch canvas. Warhol made four newspaper-headline paintings between 1961 and 1962. These were part of the larger Death and Disaster series that included newspaper imagery, and crime-scene police photography.

Andy Warhol, Skull, 1976

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

2002.4.24

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, Skull, 1976

Similar to his Death and Disaster series, Skulls represent an important shift in Warhol’s work, possibly influenced by being critically shot in 1968, an event which profoundly affected his life and art. Historically in art, the human skull represented the theme “vanitas” knows as mortality or the shortness of life. It suggested that the skull is simply a motif; a part of Warhol’s desire to evoke the human condition. Working with assistants thought out his career, Warhol was able to create multiple prints of a similar subject.

It was Henry who gave me the idea to start the Death and Disaster series. We were having lunch one day in summer… and he laid the Daily News out on the table. The headline was ‘129 DIE IN JET!’ And that’s what started me on the death series, the Car Crashes, the disasters, the Electric Chairs.

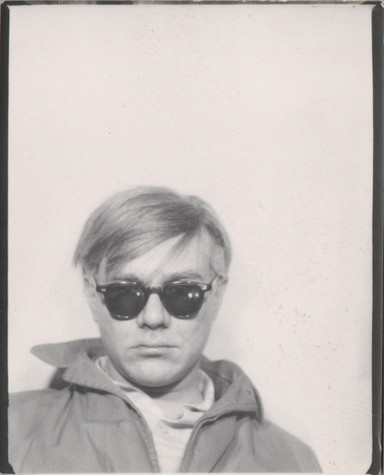

Self-Portrait Photobooth

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait , 1963

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.73.194

TC21 Object: Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait , 1963

There are a total of 204 original photo booth strips in TC21. Many of these portrait photos were commissioned to illustrate a feature in the June 1963 issue of Harper’s Bazaar, titled “New Faces, New Forces, New Names in the Arts.” The article’s subjects included architects, painters, writers, actors, dancers, composers, curators, and performers.

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait , 1963

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.73.192

TC21 Object: Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait , 1963

Andy Warhol liked the simple and quick technology of the photo booth and used these strips to create many portraits, including portraits of himself. Warhol also used photo booth images to create silkscreen portraits of socialites Ethel Scull and Judith Green, and actor Bobby Short.

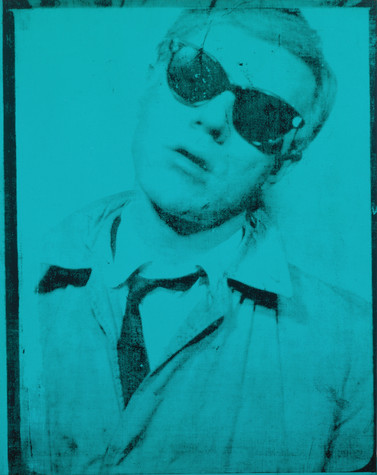

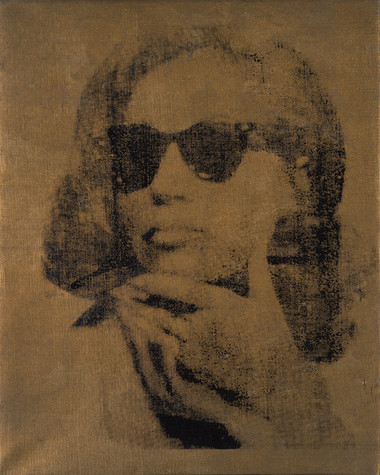

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait, 1963-1964

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.810

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait, 1963-1964

The original photo found in TC21 was made into a silkscreen and then printed onto canvas painted turquoise blue. Warhol included the dark black crop marks of the original photo as a nod to the photo booth’s unique way of printing photos.

When I did my self-portrait, I left all the pimples out because you always should. Pimples are a temporary condition and they don’t have anything to do with what you really look like. Always omit the blemishes—they’re not part of the good picture you want.

Ethel Scull Photobooth

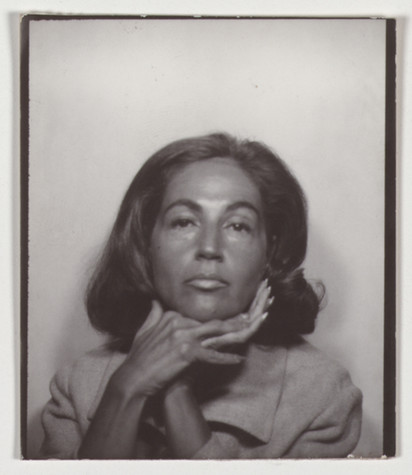

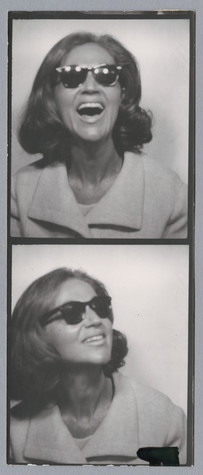

Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull , 1963

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.73.25

TC21 Object: Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull , 1963

Ethel Scull and her husband, Robert, were early and important collectors of Pop Art. In mid-1963, Robert Scull asked Warhol to paint a portrait of his wife. The resulting work is one of his earliest commissioned portraits, as well as one of his first to use photo booth photographs as the source image.

Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull , 1963

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.73.24

TC21 Object: Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull , 1963

Warhol started painting commissioned portraits in the early 1960s. These works developed into a significant aspect of his career and were a main source of his income in the 1970s. Many of his subjects were well known in international social circles, the art world, and the entertainment industry at the time.

Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull , 1963

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.61

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull , 1963

He came up for me that day and he said, ‘All right, we’re off.’ And I said, ‘Well, where are we going?’ ‘Just down to Forty-second and Broadway.’ I said, ‘For what?’ He said, ‘For the portrait.’ I said, ‘In those things? My God, I’ll look terrible!’ He said, ‘Don’t worry,’ and he took out the coins. He had about a hundred dollars’ worth of silver coins, and he said, ‘We’ll take the high key and the low key, and I’ll push you inside, and you watch the little red light.’ At the end of the thing, he said, ‘Now, you want to see them?’ And they were so sensational… I was so pleased. I think I’ll go there for all my pictures from now on.

—Ethel Scull, Painters Painting: A Candid History of the Modern Art Scene, 1940-1970, 1984

Screen Test: Ethel Scull [ST303] (1964)

Andy Warhol

Screen Test: Ethel Scull [ST303] (1964)

16mm film, black and white, silent, 4 minutes at 16 frames per second

Gift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., 1997

©2019 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved. Reproduction or downloading is prohibited.

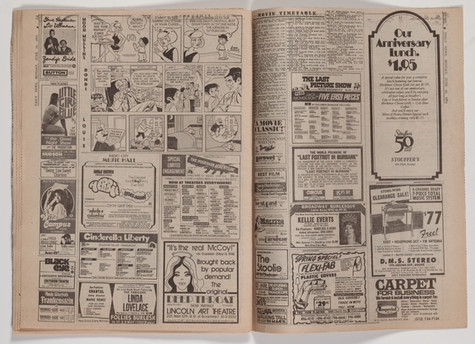

Newspaper Comics

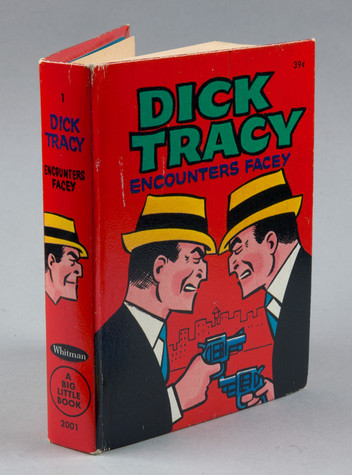

Dick Tracey Encounters Facey/A Big Little Book No. 2001, 1967

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.38

TC21 Object: Dick Tracey Encounters Facey/A Big Little Book No. 2001, 1967 , 1963.

Andy Warhol was a huge comic book fan, and collected comic books and related paraphernalia throughout his life. He transformed these unlikely bits of ephemera into fine art. Prime sources for his artwork were magazine ads, newspaper photos, comics, and the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library.

Daily News, New York Daily News, Monday, June 10, 1974

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.75

TC21 Object: Daily News, New York Daily News, Monday, June 10, 1974

Warhol enjoyed reading the daily comics and would often collect them from various newspapers to use as source material for later works.

Andy Warhol, Bonwit Teller Window Display, 1961

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Photographed by: Rainer Crone

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, Bonwit Teller Window Display, 1961

In order to create large scale paintings for window displays, Warhol would use his opaque projector to create an enlarged version of the original comic. After tracing the shapes in pencil, he would then paint in the shapes by hand. It was not long after he completed these early hand-painted canvases that he began using photographic silkscreens to create his artwork.

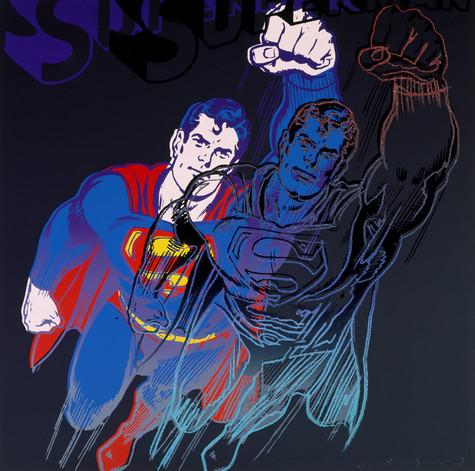

Andy Warhol, Myths: Superman, 1981

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.2452.3

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, Myths: Superman, 1981

Warhol’s fascination with Superman stems from his childhood when he was diagnosed with an immobilizing sickness and spent the majority of his time reading comic books and movie magazines. He was so preoccupied by his physical appearance, constant ailments, anxiety and insecurities that he found great appeal in the transformation of Clark Kent into Superman.

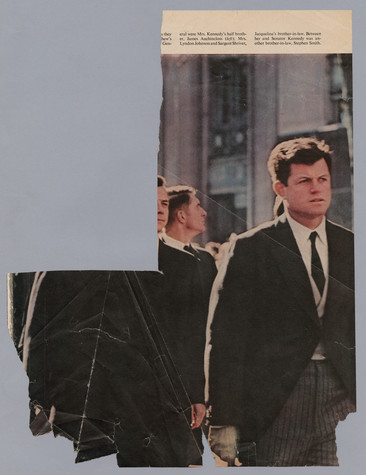

Jackie Kennedy

Magazine clipping, (possibly from Life Magazine), 1963

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.94

TC21 Object: Magazine clipping, (possibly from Life magazine ), 1963

This clipping from Life magazine depicts Jackie Kennedy (photo cut out) and Robert Kennedy in John F. Kennedy’s funeral procession. Deeply affected by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963, Warhol began a large series of portraits of Kennedy’s widow, Jacqueline Kennedy.

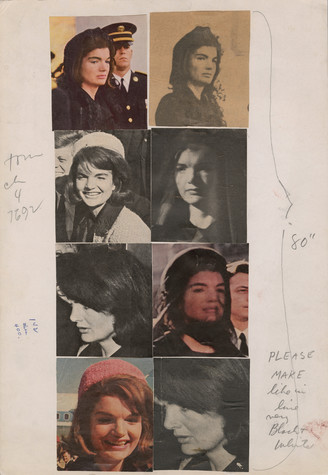

Andy Warhol, source for Jackie series, 1963-64

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.2290

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, source for Jackie series), 1963-64

To create his Jackie series, Warhol used source images such as these, taken from newspapers and magazines. These portraits were exhibited individually or in a grouping.

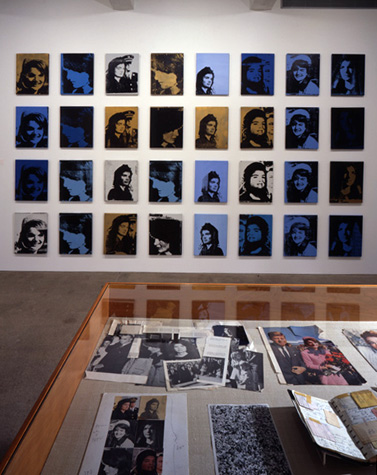

Installation of Andy Warhol's Jackie series and related source material

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Related Artwork: Installation of Andy Warhol's Jackie series and related source material

Warhol’s isolation and repetition of Jackie’s image suggest both the solitary widow and the collective experience of the witnessing nation. Commentators have remarked that it was during this time that television became a unifying force, assuming a new role in defining national consciousness. Warhol’s multiplied images offer the viewer an obsessive reenactment of this central event in United States history.

Mao

The New York Times, January 23, 1972

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

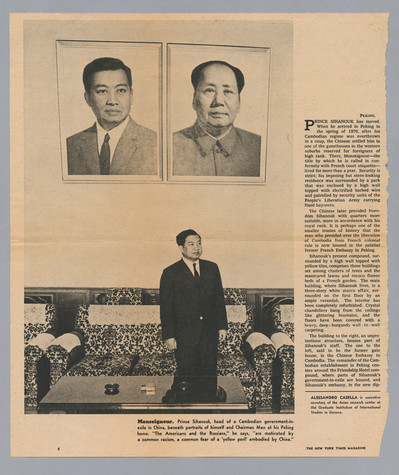

TC21.99

TC21 Object: The New York Times, January 23, 1972, (Prince Sihanouk standing beneath portraits of himself and Chairman Mao)

Warhol visited China in 1982, but his interest in Mao Tse-tung began ten years earlier as evidenced by this newspaper clipping found in TC21. This official photo of China’s revolutionary leader could be seen in farm fields, homes, businesses, and government buildings throughout China, and as the frontispiece portrait in Mao’s famous Little Red Book.

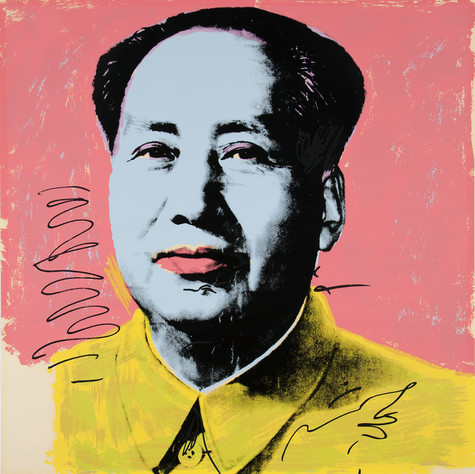

Andy Warhol, Mao, 1972

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.2401.2

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, Mao, 1972

To Warhol, Mao’s ubiquity may have seemed akin to that of Coca-Cola advertising campaigns, which urged everyone to consume the product. Warhol made dozens of paintings of Mao, as well as an edition of prints, and wallpaper. Unlike many of Warhol’s paintings of the 1960s, which display very delineated areas of color, the Mao paintings and other 1970s works are more painterly in style, showing a mixture of colors in the brushwork.

Mao, installation, The Andy Warhol Museum. Photo by Abby Warhola

Related Artwork: Mao installation, The Andy Warhol Museum

Warhol’s multiple interpretations of Chairman Mao can be seen in this gallery installation. His hand painted, photographic silkscreen portraits are exhibited on top of his repeated, stylized line-drawing of Mao with a purple face on wallpaper. Warhol’s iconic image of Mao outwardly translates this powerful, mysterious and somewhat intimidating image of Communist propaganda into a glamorized 1970s ready-made pop icon.

Factory Diary: Andy Paints Mao, December 7, 1972

Andy Warhol

Factory Diary: Andy Paints Mao,(/em> December 7, 1972

½” reel-to-reel videotape, black and white, sound, 32 minutes, camera by Michael Netter

With Andy Warhol, Jed Johnson.

Gift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., 1997

©2019 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved. Reproduction or downloading is prohibited.

Shoe Drawings

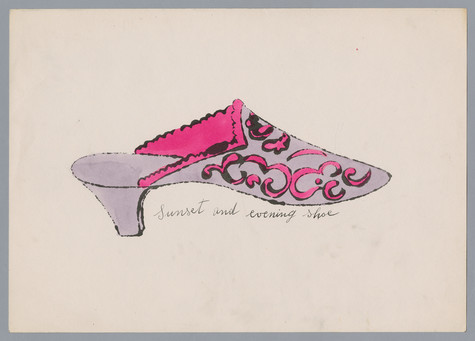

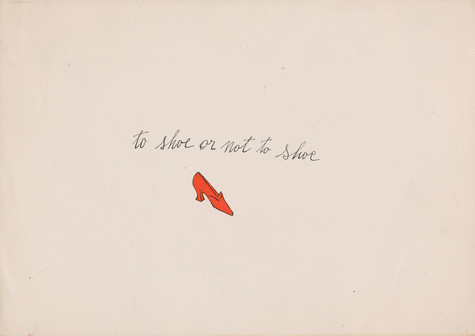

Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, from Andy Warhol's self-published book A la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, 1955

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.117.3

TC21 Object: Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, from Andy Warhol's self-published book A la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, 1955

There are three hand-colored prints of shoes in TC21 from Warhol’s self-published promotional portfolio titled A la Recherche du Shoe Perdue. This portfolio contains thirteen plates, each accompanied by a quirky one-line “shoe poem” written by Warhol’s friend, Ralph Pomeroy, and calligraphed by Julia Warhola, Andy’s mother.

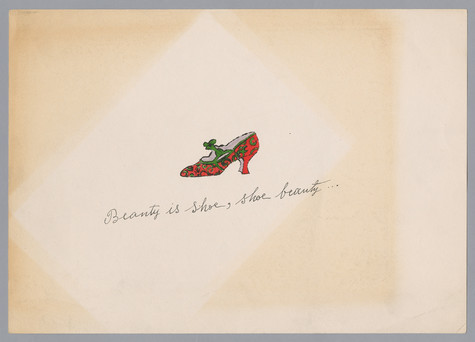

Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, from Andy Warhol's self-published book A la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, 1955

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.117.2

TC21 Object: Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, from Andy Warhol's self-published book A la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, 1955

Other versions of the portfolio have completely different color schemes due to Warhol’s “coloring parties.” For both his commercial and personal projects, Warhol would often create multiple copies of an image and invite his friends over to help add color using Dr. Martin’s Aniline dyes. Sometimes Warhol would give instructions as to what color should be added where, but other times he would let his guests fill in the outlines organically.

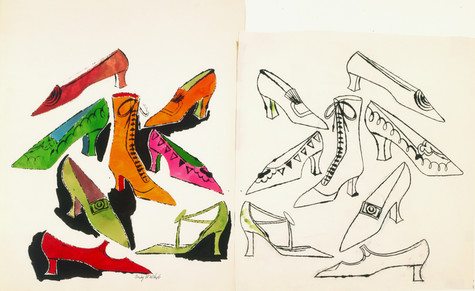

Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, from Andy Warhol's self-published book A la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, 1955

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

TC21.117.1

TC21 Object: Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, from Andy Warhol's self-published book A la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, 1955

Between 1955 and 1957, Warhol was the sole illustrator for shoe manufacturer I. Miller Shoes and made new drawings of shoes each week for ads in The New York Times. The title is a riff on Marcel Proust’s famous novel À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time, or Remembrance of Things Past).

Andy Warhol, Eight Shoes, 1950s

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.1045

Related Artwork: Andy Warhol, Eight Shoes, 1950s

Warhol used a special type of line drawing, the blotted line technique, to great effect in his commercial art of the 1950s. This technique allowed him to quickly create a variety of illustrations along a similar theme. Warhol often colored his blotted line drawings with watercolor dyes or applied gold leaf.