Pittsburgh By Maeve McAllister

Presidential candidates, dignitaries, tourists, and Kim Kardashian all do it—we all take “selfies.” The self-taken photograph composed by turning the camera lens on oneself has become an indelible (and sometimes ironic), fixture of contemporary culture.

Self-portraits, which can be seen and understood as the predecessor to today’s “selfie,” have received attention for laying the framework for this digital portraiture. Over the past year, Warhol’s self-portraits have been enjoying their own 15-minutes of Internet fame.

In early 2014, Huffington Post reported that Andy Warhol is “The Original King of Selfies.” In May 2015, The Hollywood Reporter remarked, “Sorry, Kim Kardashian,” Andy Warhol is the originator of the selfie game in a story about a Sotheby’s auction of a collection of Warhol’s celebrity and self-portrait Polaroid shots. The New York Post published a story in August 2015, titled “Andy Warhol Instagrammed his life before Instagram existed.” In July 2015, The New York Times made a case for a scholarly analysis of selfies, and the list goes on.

Taschen, a reigning name in art book publishing, released Andy Warhol: Polaroids 1958–1987 this past fall.

It is safe to say that in 2015 Warhol’s selfies had a strong, self-indulgent moment. But what is the role that the selfie plays in the context of a museum, and what do these shots reveal about the person behind the camera? Walking through The Andy Warhol Museum, I found that the artist’s self-portraits hold an important place for themselves on the institution’s walls.

In his book, About Face: Andy Warhol Portraits, critic Nicholas Baume writes, “Clearly, Warhol was intrigued by the human face. Throughout his career, he constantly drew, painted, filmed, photographed and described it” (86).

Warhol left behind a vast collection of self-portraits, including Polaroid prints and silkscreen paintings, spanning from young adulthood to death.

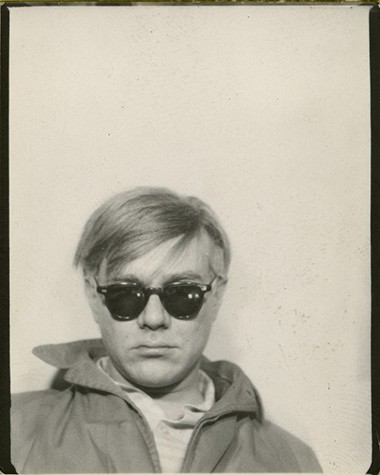

An early image cut from a photobooth strip reveals a casual, cool-kid Warhol. With dark black shades, the artist used the photobooth to capture his own image and experimented with self-portrayal. The result is strikingly similar to much of what can be seen on a young adult’s Instagram account today.

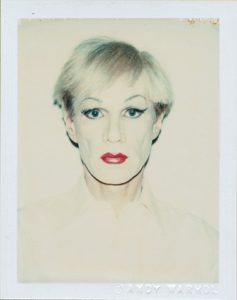

Later in his career, Warhol employed his Polaroid camera for a larger project. Called Ladies and Gentlemen, the large-scale portrait series using drag queens as models was commissioned by an Italian art dealer in 1974 (Catalogue Raisonne n. pag). In 1981 Warhol worked with photographer Christopher Makos on a series of Polaroid self-portraits depicting himself in drag.

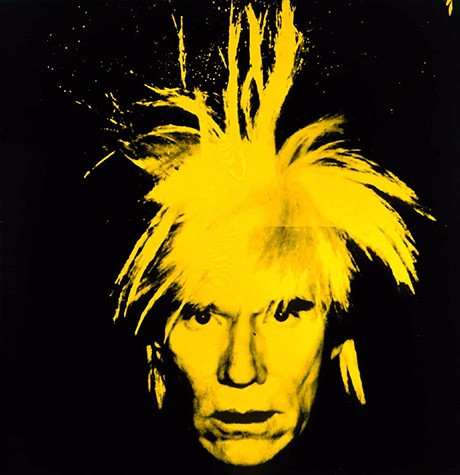

By the end of his career, Warhol’s self-portraits continue to change as he experiments with his image. His 1986 self-portrait series, completed just months before his death, shows a gaunt face and wild hair. This self-portrait, one of the last he created, appears to capture his feelings about his late self-image and is largely understood as an acknowledgement of death.

Celebrities’ Instagram posts often collect millions of “likes” and tens-of-thousands of comments by turning cameras on themselves, showcasing their bodies, and perhaps their acceptance of them.

I wondered, then, how does a selfie function in the context of a museum?

Warhol’s self-portraits give us an insider’s look into the artist’s personal sphere. From his youthful photobooth moments to his dramatic silkscreen self-portraits, the changing images allow us to observe his lifelong experimentation and to understand his cultural fixations.

Maybe, however, the answer is much simpler, as Warhol is quoted as saying: “I paint pictures of myself to remind myself that I’m still around.”

Baume, Nicholas. “About Face: Andy Warhol Portraits.” About Face: Andy Warhol Portraits. Cambridge: MIT, 1999. 86-98. Print.

Printz, Neil, and Sally King-Nero, eds. The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonne: Paintings and Sculpture Late 1974-1976. Vol. 04. New York: Phaidon, 2013. Print.