“…it doesn’t go together. But sometimes it does—suddenly the beat of the music, the movements of the various films, the pose of the dancers, blend into something meaningful, but before your mind can grab it, it’s become random and confusing again. Your head tries to sort something out, make sense of something. The noise is getting to you. You want to scream, or throw yourself about with the dancers, something, anything!”

– Larry McCombs in his review of the EPI, “Chicago Happenings,” Boston Broadside, July 1966

Upon entering the Warhol Museum’s new Exploding Plastic Inevitable Gallery, it felt like I had crossed into an alternate universe. Although it’s not quite the same as the production seen by Larry McCombs (no live dancers, unfortunately), the Gallery maintains the confusing bombardment of sight and sound he describes—I couldn’t be sure of exactly what I was looking at or how each sensory component fit together at first. The Velvet Underground plays in surround-sound. Over here is Gerard Malanga performing S & M acts, over there is a giant blinking eye, and all the while random patterns and colored lights move around and overtop of the many layered images on the walls. Your mind adjusts, but the scene constantly changes and it’s hard to take it all in at once.

The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, Warhol’s multi/intermedia production, premiered at the Dom, a downtown Polish meeting hall, in April 1966—the same month the artist showed his cow wallpaper and Silver Clouds at the Leo Castelli Gallery uptown. McCombs’s review captures a glimpse of what spectators experienced during a performance in Chicago, one of the stops along the EPI tour in the spring and summer of that year. At its height, the EPI featured musical performances by the Velvet Underground and Nico, while anywhere from 3 to 5 of Warhol’s films such as Eat, Sleep, and Vinyl, as well as Screen Tests of band members were projected on multiple screens. A mirrored ball hung from the ceiling and floor, reflecting lighting overlaid by colored slides with patterned cut-outs, changed by hand. The addition of strobe lighting, Gerard Malanga, Mary Woronov, and Ingrid Superstar dancing on stage, as well as the movements of the rest of the crowd all contributed to a multisensory experience.[1. Joseph, “‘My Mind Split Open’: Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable,” 81.]

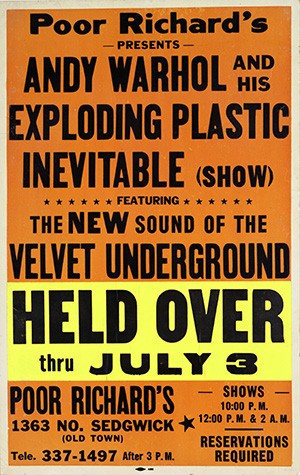

letterpress and relief print on cardboard with printed paper sticker

22 1/8 x 14 in. (56.2 x 35.6 cm.)

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

The EPI stemmed from a series of Warhol’s experimentation with the world of rock music and intermedia performances. As early as 1963, Warhol was in the midst of forming a rock band called the Druds with Patty and Claes Oldenberg, Lucas Samaras, Jasper Johns, Walter De Maria, La Monte Young, and Larry Poons. This project, albeit short-lived, demonstrates Warhol’s early engagement and experimentation with music (for more on the Druds, see Branden Joseph’s “No More Apologies: Pop Art and Pop Music, ca. 1963” in Warhol Live: Music and Dance in Andy Warhol’s Work). In the fall of 1964, Warhol collaborated with La Monte Young on an installation for the Second Annual New York Film Festival.[2. David Bourdon, Warhol (New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1989): 190.] The installation consisted of excerpts from Eat, Sleep, Kiss, and Haircut, played in a loop with a soundtrack composed by Young consisting of 4 different, singular tones played at maximum volume. An early trial of intermedia performance, the installation was ill-received, called a “festival side-show” [3. One-page, typed press release, in Time Capsule 37, Warhol Archives.] by critics and eventually shown without Young’s loud and imposing soundtrack.

Barbara Rubin and Gerard Malanga introduced Warhol to the Velvet Underground in late 1965 at their performance at Café Bizarre. He decided to become their manager, allowing them to practice at The Factory space and placed Nico, a striking German model, actress, and singer, just newly arrived in New York, as their frontwoman.[4. Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, Popism: The Warhol Sixties (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980), 180-181.]

“She was mysterious and European, a real moon goddess type.”

– Warhol, POPism, p. 183

The group’s initial performances were entitled Andy Warhol Up-Tight, first appearing at the annual New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry dinner at the Delmonico Hotel in January 1966. This particular performance included the Velvet Underground and Nico with Gerard Malanga and Edie Sedgwick dancing on stage. Filmmakers Barbara Rubin and Jonas Mekas rushed into the crowd, shoving flood lights and cameras into the faces of the stunned attendees, asking questions such as “Is his penis big enough?” and “What does her vagina feel like?” Eventually, the name Andy Warhol Up-Tight morphed into the Erupting Plastic Inevitable and finally the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, dropping Rubin and Mekas, replacing their guerrilla-like assaults with a complete auditory, synesthetic experience.[5. Ibid., 183-184.]

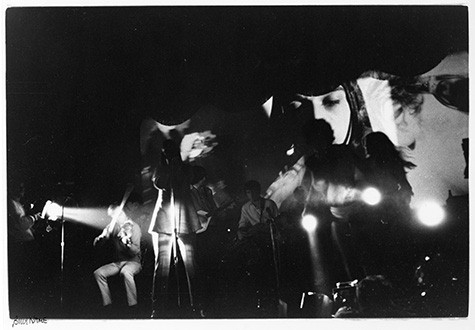

gelatin silver print

11 x 14 in. (27.9 x 35.6 cm.)

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Museum Purchase

© Billy Name Linich, http://billyname.net

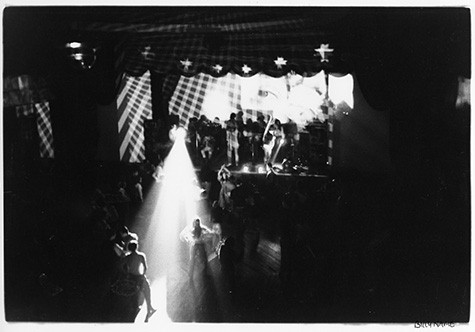

gelatin silver print

11 x 14 in. (27.9 x 35.6 cm.)

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Museum Purchase

© Billy Name Linich, http://billyname.net

As part of the Warhol Museum’s rehang of the collection for its 20th anniversary, the museum has acquired a number of new spaces, including our own evocation of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable—complete with a revolving disco ball. Located on the 6th Floor, museum-goers can enter a room lined with posters advertising the EPI and the Velvet Underground and examine ephemera including some of the actual colored and patterned slides, designed by Jackie Cassen, that were used to overlay light projections. Behind a heavy black velvet curtain lies the Museum’s interpretation of the 1966-67 EPI shows. Put together by our Assistant Curator of Film & Video Greg Pierce, and Pittsburgh-based filmmaker and designer Michael Johnsen, the room features 17 projectors, 12 of which project Warhol’s films including More Milk Yvette and EPI Background reels (three of which have not been publicly shown since the original ’66-’67 performances) on all four walls, overlapping and layered over one another. The arrangement of the films is based on photographs taken of the EPI performances and reinterpreted in order to capture the visual aspects of the multimedia production to fit the Museum space. The other 5 projectors cast various randomized light patterns through colored slides created from the originals. Viewers can hear the drones of the Velvets taken from live recordings, providing the closest conveyance of the band’s distinct live sound.

Initially, I saw the EPI as a clash of disparate components and was surprised, confused, and a little amused at the oddity of the production. But Warhol was never one to remain static—the EPI was just one example of his innate ability to thoroughly explore the newest scene while lending his creativity to different media. Diving deeper into my research, the production started to make sense as a cohesive work within the context of Warhol’s other pieces—particularly his experimentation in film—calling to mind Wagner’s gesamtkunstwerk, or a total work of art. I realized that the EPI was not simply meant to shock or entertain but to interact with and envelop the audience in a way that made the viewers an essential part of the work.

Walking into the Museum’s EPI Gallery only brought this unique experience to life and created a tangible understanding of how each part of the production fit together to form this participatory experience. I was surprised at how the sights and sounds encourage viewers to be active and walk around the entirety of the space, almost moving with the constantly shifting components. The EPI Gallery provides visitors a fascinating new perspective on Warhol’s artistic practice and, for me, helped to reveal an artist whose inventiveness went far and beyond his iconic screenprints. Be sure to check out the Museum’s new EPI Gallery on the 6th floor during your next visit to see a glimpse of Warhol’s inimitable production.

Karen Lue is the Milton Fine Curatorial Fellow for the summer. She is a rising senior at the University of Pittsburgh, studying History of Art & Architecture and Economics.

For an in-depth analysis of Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, see Branden Joseph’s “‘My Mind Split Open’: Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable,” Grey Room 8 (Summer 2002): 80-107. Much of my understanding of the EPI was shaped by Joseph’s article, which is one of the only pieces of writing that draws conclusions from the EPI in the social and cultural context of the time period.