Paola Pivi: Creation Stories and Making Possible the Impossible

Image Gallery

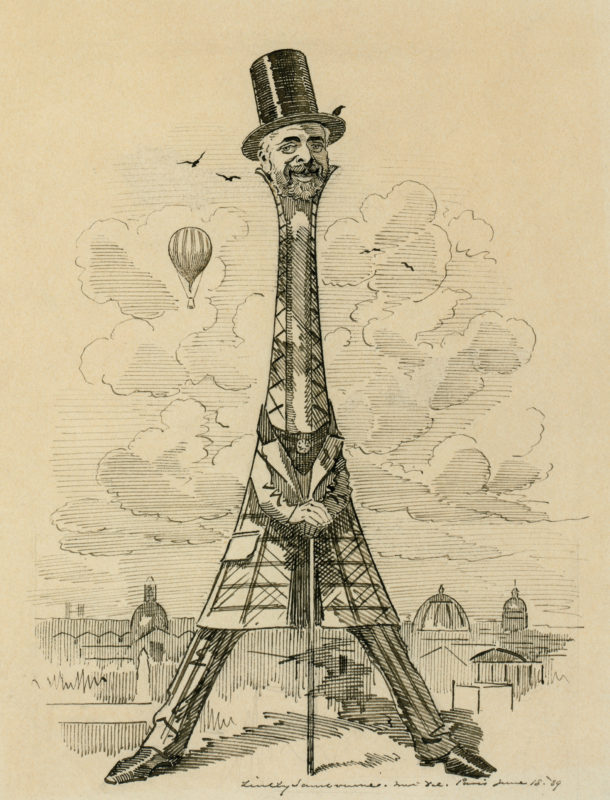

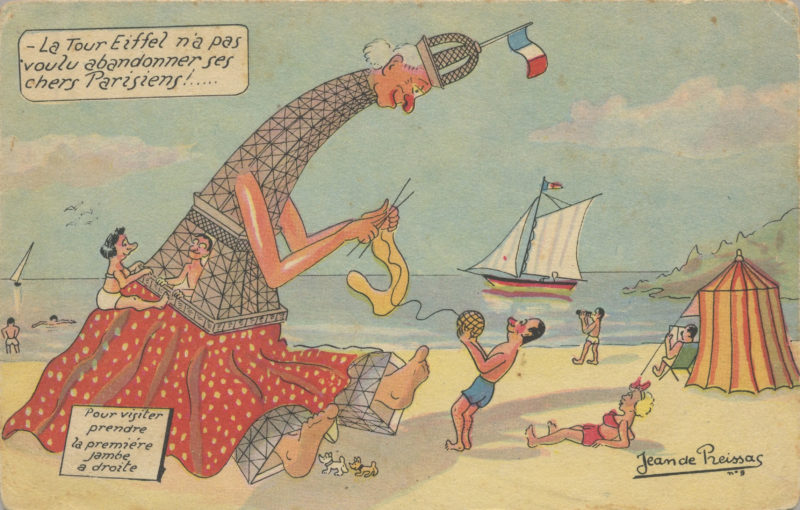

Pivi’s manicured landscapes featuring captivating creatures represent more than just face value. Pop artist Andy Warhol allegedly told a journalist, ‘If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.’1 While the statement apparently dismisses artistic depth in favour of superficiality, Pivi’s work presents similar questions because her intertwined connection between man and beast takes place within a manufactured world that has deeper significance than just serving as a setting for beautiful and baffling photographs. Pivi was once called the ‘high priestess of Cockaigne’, a medieval fantasy realm filled with impossible excess and imaginary pleasures;2 however, she works very much in reality and in the present. For example, the series Yee-haw (2015) began with an essentially straightforward concept: releasing horses inside the Eiffel Tower. A simple idea yet complicated in execution. It is like a wedding cake: people know what it is, but do not often know how to make one. In Yee-haw the equine animals and the Parisian monument align in beastly matrimony.

The Eiffel Tower was originally built for the entrance of the Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair hosted in 1889. The 1,000-foot-high iron structure was funded and designed by the engineer Gustave Eiffel (also credited for designing the interior structure of the Statue of Liberty). Although conceived as a temporary construction, through negotiations it remained in place and has since become a pilgrimage site of national pride, celebration, veneration, protest, suicide, mourning, commemoration and, most of all, tourism.

Image Gallery

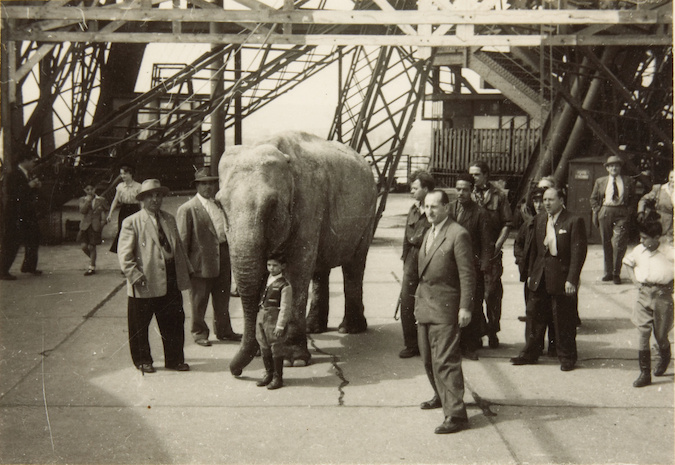

The elephant from the Cirque d' Hiver-Bouglione on the first floor of the Eiffel Tower on July 4, 1948.

Pivi’s proposal became possible with an invitation from Virginie Coupérie-Eiffel, the great-granddaughter of the tower’s creator. A champion rider and event organizer herself, she asked Pivi to design the annual poster for Paris Eiffel Jumping, an international equestrian competition that takes place near and around the tower.3

Historically horses have been a constant presence around the area, mostly as a mode of transportation prior to the advent of the automobile. Early photos show horse-drawn carriages around the tower. In Yee-haw, as with previous projects, Pivi removes humans from the photo-performance and confines our participation to the role of passive observer. Four professionally trained horses, two white and two brown, spent several early mornings being photographed on the tower’s first level platform before the site opened to the general public. Transformation quickly ensued as the horses blended with the metal columns, at times becoming almost one and the same, depending on the sunrise and the camera angle. Pivi acknowledges that such a setting ‘can highlight the design of the animal, as if there could have been a designer’.4 The four riderless horses swirl in joy, recreation and liberation, animals and tower uniting in a single spectacle. Surprisingly the site is already known for odd encounters, such as when a circus elephant visited the first level platform in 1948 and when farmers grazed approximately 250 sheep at its base in 2014, in protest at what they saw as the government’s over-protection of hungry wolves.5

The project’s title, Yee-haw, is an expression of excitement related to the classic American ‘Wild West’. Cartoons, films and literature stereotypically depict a male cowboy yelling ‘yee-haw!’ while mounted on his steed. Pivi’s title hints at the absent riders, yet also links the work to early French exposure to cultural Americana. In 1889, at the same time as the Exposition Universelle, horseman and impresario Buffalo Bill Cody was touring through Europe with his ambitious and theatrical Wild West Show. In Paris it rivalled the world’s fair in popularity and spectacle. While Cody embellished life in the American West, then still a colonized frontier, he did in fact introduce a diverse cast that included Native Americans, Mexicans and women, as well as North American wildlife including buffalo, mustangs, mules, bears, moose, elk and Texas Longhorn cattle. The show involved races, riding, re-enacted battles and exaggerated horseplay, (somewhat less decorous than today’s Paris Eiffel Jumping). Dazzled by the exoticism, famed French artist Rosa Bonheur (1822–99) visited the grounds of the Wild West Show and spent hours observing the performers and animals, resulting in over fifty known sketches and paintings.6 Cody even posed for a portrait riding on a white horse. For Bonheur, Cody and his show represented unrestrained freedom and independence (that is to say, the essence of ‘yee-haw!’). As a celebrated animal painter, Bonheur admired the natural world but also enjoyed the one that Cody fabricated around it, in that instance the mythology of the American West and its trappings. Pivi too is enamoured by nature, as well as by the world that mankind has constructed, which in her eyes, like the Eiffel Tower full of horses, is very much alive.

Image Gallery

Rosa Bonheur

Col. William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) (1889)

oil on canvas

From monuments to mattresses, Pivi anthropomorphizes inanimate objects through unassuming display. They too become a living organism in her practice. Among the plethora of man-made stuff whose creation and purpose she reconsiders are the thousands of objects that make up Guitar Guitar (2001). Pivi inventoried and coupled identical pairs of objects like Noah filling his Ark. Installed only twice (!), among the myriad items Pivi included were two automobiles, two motorcycles, two exercise bikes, two football tables, two lamps, two Hello Kitty toasters and, two Mickey Mouse balloons. All laid out, non-functioning and standing in for the absence of humans, they too—much like Pivi’s animals—are re-created through her imagination.

For a new project, in production at the time of writing, Pivi is collecting hundreds of pairs of shoes. A decade ago, the world’s oldest known leather shoe was discovered in an Armenian cave. The 5,500-year-old tanned leather shoe reveals our long-term relationship with footwear, from necessity to narcissism.11 Also tracing our steps, though in more modern terms, Pivi’s project Untitled (shoes) (2022), involves over one hundred pairs of brand-new shoes each with a matching identical pairs, being worn by volunteers and then returned to the artist, before finally being secured on the walls of a museum like trophies, their soles mounted onto the wall’s surface and lined up two by two, in a grid. For example, two pairs of blue satin jewelled Manolo Blahnik heels, made popular in the TV show Sex and The City, will join a collective of dozens of other brands, styles, shapes, colours and materials, from animal leather to industrialized rubber to woven canvas. Each of the worn pairs, bearing their wear and tear like scars, will act as a diary of each individual’s daily rituals from the commencement of the project to the moment of being reunited with their matching unworn pair in Pivi’s installation. These fetishized objects—conceptual effigies of man and material—resemble the displays found in anthropological museums.

There is a phrase about ‘walking a mile in someone else’s shoes’ to better understand their experience or perspective; Pivi, however, goes one ‘step’ further by literally showing us the actual shoes worn by people around the world. The degree of wear and tear is highlighted when placed alongside their pristine partners. By retiring the shoes for the sake of art, Pivi con-siders the superficiality of certain types of footwears and their design. She may be depriving them of their function, yet the shoes collectively communicate the personal style and hours of human labour involved in this participatory project. The artist states, ‘Art is the thing that can change the way people think and perceive…It’s like an exchange of communication—sharing a large amount of information in a very condensed time.’7 The sneakers, sandals, high heels, loafers and array of various other types of footwear collectively tell a creation story, Pivi’s creation.

Pivi also spots a dilemma in the creation process: can one go too far? Absolutely not. Her installation Untitled (muskox) (2008) summarizes the dichotomy of life and death in the twenty-first century. Yet another strategic doubling, it couples a muskox and a mound of coffee beans. Beast and beans, both altered by human intervention, make a formidable, dark monument of fur and fragrance. This relatively unknown bovine is surrounded by thousands of tiny roasted coffee beans, meticulously piled as high as naturally possible. The work is a vanitas still life, pointing to the ephemerality of modern man (who is, yet again, unseen). The muskox and the coffee make an evocative banquet for human survival. Muskoxen are Arctic natives with shaggy hair and curved horns, and emit a pungent odour during mating season. Living in herds, they are resilient mammals that can endure extreme climates. In 1902 one was introduced to New York’s Central Park Menagerie (now Zoo), along with a walrus, by the infamous explorer Robert Peary.8 Muskoxen have also been a sustainable resource for Inuit and Indigenous communities in Canada, Greenland and Alaska. In 1917 another Arctic explorer advocated them as an American meat source, but the endorsement failed.9 Today muskoxen lack such a public platform but Pivi’s artwork gives them new visibility within a sequence of images of exotic creatures (ostrich, alligator, donkey, leopard, performing horses), paired with manufactured goods.

Coffee has appeared in Pivi’s practice on more than one occasion (One cup of cappuccino then I go, 2007; and It’s a cocktail party, 2008). Far more common than muskoxen, coffee consumption can be found in many cultures, especially in Pivi’s native Italy. Coffee beans, the processed seeds of the coffea plant, are specifically grown in warm equatorial regions between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. This curious pairing— hot and cold; large and small; hard and soft; stimulated and sedated; sterilized and fertile—aligns with Pivi’s reconsideration of the lifecycle of living and industrial matter. Coffee is valued and stimulates us; however, here, it remains unbrewed and failing to fulfill any purpose. The muskox, very much dead and now lacking its musky smell, stands alone, committed to a life as memento mori. Combined, the two function very much like an existentially loaded poop emoji: ‘shit happens’.

Through her visions of wearing out hundreds of ready-made shoes or of beautiful horses claiming spaces where they should not be, Pivi materializes a brand-new world that is unconventional and entertaining, but also thought-provoking once you get past the surface. Yee-haw has become Pivi’s final photo-performance with live animals. However, the artist did have one further unrealized creation: placing a giraffe on top of a skyscraper. Just imagine that! It reminds me of a joke: How many animals can jump higher than a skyscraper? All of them, skyscrapers can’t jump. Perhaps not, but with Paola Pivi anything is possible.

Warhol At Pitt: When Andy Returned to Pittsburgh

The first mention of Andy Warhol in Pitt News occurred on April 3, 1967, in an advertisement for the record, The Velvet Underground with Nico, the debut album of the rock band that Warhol managed at the time.10 The ad humorously refers to Warhol as “the daddy of Pop Art” and describes the record as “Warhol’s very first, very far-out album.”11 The ad copy seems to imply that Warhol may actually play music on the recordings, when in fact he just managed the band and executed the multimedia light shows for their live performances. Overall, the ad conveys how much the Velvet Underground’s success was tied to Warhol’s name recognition during their early years.

A few months later, Warhol’s artwork was exhibited in Pittsburgh for the first time since his years as a pictorial design student at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). The Pitt News mentioned Warhol as one of the “established artists” featured in the 1967 Carnegie International exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art, which University of Pittsburgh students could attend for free.12 This exhibition marks the beginning of an increase in showings of Warhol’s art and films in his hometown of Pittsburgh. Although, interestingly, research shows that during the late 1960s, Warhol’s films traveled to Pittsburgh more frequently than his paintings.

Image Gallery

Paul Morrissey near the Cathedral of Learning, 1968.

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh;

Founding Collection,

Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.3.15016

Warhol’s presence in Pittsburgh reached a notable peak in February and March of 1968. During the six-week period of mid-February to late March, films by Warhol, about Warhol, and inspired by Warhol were screened at CMU and a café near the University of Pittsburgh; the Frick Fine Arts gallery exhibited Warhol’s artwork in a Pop Art group show; and Warhol himself visited the Pitt campus to conduct a lecture and film screening.13 Even though more film screenings took place at CMU than the Pitt campus, The Pitt News made a point to advertise all of these cultural events to the student body.14 Students could view artwork by Warhol and five other major Pop artists at the Frick Fine Arts gallery, and even purchase prints for relatively affordable prices ranging from $6 to $70.15 Once news arrived that Warhol would visit campus in person, The Pitt News listed an application for a chance to have lunch with the artist after the lecture.16 Suddenly, Warhol became more accessible than ever to Pitt students, but his physical accessibility did not necessarily result in more acceptance from the entire Pittsburgh community.

Andy Warhol and some of his friends, assistants, and Superstars visited the University of Pittsburgh on March 26, 1968. Although announcements prior to the event had advertised that Warhol would deliver a lecture titled “Pop Art in Action,” he apparently decided to simply screen an excerpt from one of his films and then take questions from the audience.17 Coverage of the event in both The Pitt News and The Pittsburgh Press conveys a bemused but cynical assessment of what transpired. Both journalists noted that Warhol had managed to fill the Student Union Ballroom to the brim; he spoke to a massive crowd of “more than 500 assembled beards and non-beards.”18 The Pitt News described the audience as “a few token straights in suits or crew necks, but, primarily, the listeners were long-haired and bedizen in beads or buttons.”19 A writer for The Pittsburgh Press went so far as to call a student he spoke to “a slightly chubby blonde ‘witness’ known only as ‘Melda,’ who looked as if she had been bounced over the Alleghenies behind a 40-mule team for this purpose.”20 Clearly Warhol had attracted a large swath of the Pitt counterculture; but Warhol’s film and Q&A session may have left his fans rather befuddled.

George Thomas never mentioned the title of the film in his article for The Pittsburgh Press, and Paul Anderson’s article for The Pitt News incorrectly referred to the film as “Stars” and “Starts.”21 The actual title of the film was “****” and most Warhol scholars call it “Four Stars.” Four Stars is a 25-hour movie that was only screened once in its entirety, but Warhol broke down the film into several shorter movies for other screenings.22 In The Pitt News, Anderson described the film as “a garbled compendium of every cinematic trick known to man” that included “a series of impromptu jokes (often very racy) and extemporaneous discourse on such varied topics as Vietnam, Truth, Hell’s Angels, Shriners, Santa Claus, Magic Marker pens, psychic echology [sic], and the Ku Klux Klan.”23 In The Pittsburgh Press, Thomas called it one of Warhol’s “double-exposure adult home movies with a presumably (but not clearly) nude co-ed on what passed for an LSD ‘trip’ superimposed on continuous shots of a platform speaker presumably ranting against war.”24 In short, both journalists sound quite baffled and overwhelmed by the content of Four Stars. To be fair, having such a reaction to any Warhol film is not uncommon.

Image Gallery

Paul Morrissey and Viva near the Cathedral of Learning, 1968

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh;

Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.3.15017

When it came time to take questions, both journalists noted that two of Warhol’s assistants, Paul Morrissey and Viva, did most of the talking. All three speakers kept it light even when things got personal. As documented in The Pitt News, “when a certain hippie asked Viva if Superstar Nico went both ways she replied, ‘Well I roomed with her for a year and she never came my way.’”25 Indeed, reporting on the event indicates that the discussion revolved around the sexuality of many members of Warhol’s entourage, as well as Warhol himself. Anderson noted, “a few of the queries were downright antagonistic and questioned Warhol’s sexual orientation.”26 While Thomas initially tried to avoid addressing the sexual taboos in his article for The Pittsburgh Press, declaring “then there were the rapid-fire exchanges on sex—but this is a family newspaper;” he eventually recorded the queer outcome of Warhol’s upcoming Western, Lonesome Cowboys, which “started out as a Romeo-and-Juliet, boy-gets-girl movie—but they ran out of girls so the boy wound up with a cowboy.”27 Rather than expend many words exploring the implications of Warhol’s queer cinema, both authors simply ended on the positive note that “it was all in fun,” and everyone seemed to have a good time.28

Warhol’s visit to Pitt encapsulates two interesting trends in the coverage of the artist in The Pitt News in the late 1960s. First, Warhol agreed to do a lecture on Pop Art, but what he delivered was a film screening. In 1965, Warhol had announced to the press that he was “retiring from painting” to focus on making films; and while the declaration was mostly a publicity stunt and he never stopped painting altogether, he did focus more of his energy on filmmaking until the early 1970s.29 In fact, of the 19 mentions of Warhol in The Pitt News from April of 1967 until June of 1970, only 5 refer to Warhol in the context of visual art, while 12 refer to him in the context of experimental film. It is remarkable that Warhol had made such a name for himself as a filmmaker during these years, considering his reputation today primarily centers around his paintings.

The other striking trend in Warhol’s coverage in The Pitt News is the rather matter-of-fact acknowledgement of Warhol’s homosexuality and the queer content of his films. In another article by Paul Anderson on the topic of underground cinema, he wrote, “the Little Boy Naughty of the underground movement is ex-Pittsburgher Andy Warhol, who delights in filming seldom seen scenes of a world in which the queen’s word is law.”30 He went on to discuss Warhol’s most successful film, Chelsea Girls, and explained that “straight audiences all over the United States are thrilling to its explicit scenes of drug-taking, homosexuality, and lesbianism.”31 In an article about a screening of Warhol’s film My Hustler at the Crumbling Wall Coffee House, the author actually quoted Warhol’s summary in his own words: “It’s about an aging queen trying to hold on to a young hustler and his two rivals, another hustler and a girl; the actors were all doing what they did in real life, they followed their own professions on the screen.”32 Warhol revealed that his film included real queens and hustlers playing themselves, and The Pitt News apparently had no qualms about sharing this information with impressionable young college students. This may not indicate that all Pitt students fully accepted Warhol’s queer filmmaking; as Anderson suggested in his assessment of the success of Chelsea Girls, the “straights” may have simply found the novelty of Warhol’s queerness to be intriguing. However, since the art world subjected Warhol to so much straightwashing throughout his career, it is nevertheless significant that Pitt students at least had a clue about Warhol’s sexuality back in the late 1960s.

Pittsburgh did not have many opportunities for a young, gay artist when Warhol moved away in 1949. By the time he returned to Pittsburgh two decades later, the city had started to change. Local galleries and museums embraced his visual art; cafes and universities screened his bizarre films; newspapers advertised his avant-garde rock band. He only visited once in 1968, but his legacy has had a huge presence here for years. Despite spending much of his adult life in New York City, Warhol had a major role in Pittsburgh’s cultural transformation.

Jessica Beck in Conversation with Franklin Sirmans

JB: Franklin, you have been an integral part of this exhibition, and I was so gratified when you expressed interest in the show. I could immediately see these historical artworks looking fresh and new hanging in your sunlit galleries in Miami—a space that feels contemporary and bright. What first drew you to this exhibition and why did you feel it would be a good fit for the Pérez?

FS: I love Andy Warhol, but to consider Warhol in the context of Miami the same way one might in New York, San Francisco, or Chicago would be wrong. The beautiful thing about well-curated exhibitions is that the most successful ones always lead to new ways of thinking about the artist and provide the catalyst or impetus to look at the work in new and potentially exciting ways. That’s what you’ve done with this show. More important, your proposal looks at Warhol and Marisol together as friends, colleagues, and working artists who hit the scene at the same time. This original vision was the linchpin. While our holdings of Marisol are limited, there is a wonderfully rare and important sculptural work constructed of paper—a portrait of the dealer Sidney Janis—that Marisol made in 1969. Of course, your show is about the 1960s and these two incredible artists coming into their own, and where do they come out together but through the relationship with Janis! Another exciting aspect of this relationship is the fact that our Marisol piece was given to the museum by Manuel Gonzalez, who is now a Miami resident, but in the early 1960s he worked at Sidney Janis Gallery, which is how he got the work in the first place.

JB: That connection was a nice discovery during this process. Along with Janis, prominent gallery directors such as Leo Castelli and Eleanor Ward had immediate and direct influences on the success of Marisol’s and Warhol’s early careers. At that moment, these galleries were just opening, but there was also a rise in art criticism taking shape in New York. In 1966, for instance, Lucy Lippard defined New York Pop as “art determinedly of the present,” claiming it was created by Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, James Rosenquist, and Claes Oldenburg, whom she called “The New York Five.”1 We have still not expanded this definition, and artists outside of this group of white men, including Marisol, are often relegated to the international scene, separate from the New York origin story. Do you see this exhibition as furthering a more progressive history of Pop, which is my ultimate goal with this show?33

FS: We are blessed by the dynamism of art history, which has produced so many broad and more inclusive histories. I am reminded of relatively recent exhibitions such as Pop América, 1965–1975, The World Goes Pop, and International Pop.34 Marisol’s work was in each of them. The expanded field created by these shows and others is part of our mission. Recently at PAMM, in 2019, we presented a retrospective of the work of Beatriz González, another woman who should be better known, especially in the orbit of Pop Art and the canon. An accompanying program of that exhibition was called “Defining Pop Art: Beatriz González and Andy Warhol.”

JB: These exhibitions have solidified Marisol’s name in the movement, but they are focused on International Pop. I’m committed, however, to reclaiming her place within the New York origin story of Pop. For Marisol, this notion of nationality and home was always in flux. She proclaimed that she was a citizen of the world—born in Paris, growing up in Los Angeles and Caracas, and then making her own way to New York. At Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, she was included in four Carnegie Internationals (1958, 1964, 1967, 1970) and even though her work was often grouped with that of US artists, she was invariably listed as a Venezuelan artist. All the while, her work was being made and sold in New York, and she was in fact redefining the New York Pop scene. Do you see these slippages as part of the story of her erasure? It seems that her resistance to claiming a single nationality also reveals a larger issue within the framework of art history.

FS: It’s weird, and we all have our hands in it. In some exhibitions her nationality is given as French, and in others it’s Venezuelan. I think traditional structures have often had a hard time with hybridity and pluridimensionality. Hyphenated existences distort the narrative. Our labels stick to the fact of where one was born and where one lives, which can be limiting and unproductive.

JB: Fame and notoriety are interesting points of connection for Marisol and Warhol. Marisol ran from her early success at the Leo Castelli Gallery, but by 1961 she was at the center of the burgeoning New York art scene and certainly ahead of Warhol. In 1962 Life magazine included her in its list of the “one hundred most important young men and women in the United States.”35 Two years later, thousands crowded her second solo show at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery, which attracted the media’s attention and, I’m sure, Warhol’s. Yet, even with this press and notoriety, her name was dropped from history, whereas Warhol’s became synonymous with Pop. There is also this myth that Warhol achieved fame and success early and almost immediately in New York, which is not the case. It took ten years for him to get his paintings shown in galleries. How do you understand this tension between Marisol’s success and her eventual disappearance in the record?

FS: She had already made so many great signature works, so the recognition was certainly well deserved: The Kennedy Family (1961), Love (1962), and The Family (1963), among them. Perhaps ironically, while Marisol was included in a mass market, truly popular magazine such as Life, Lippard, writing in 1966, thought that her work was actually “a sophisticated and theatrical folk art.”36

JB: Yes, exactly, but the great thing about this quote is that Lippard contradicts herself just two lines later. Of Marisol she writes: “Hers is a sophisticated and theatrical folk art justifiably reflecting her own beautiful face. But it has little to do with Pop Art, aside from its deadpan approach and touches of humour. Marisol rarely, if ever, uses commercial motifs, although her John Wayne and The Kennedy Family would fall within Pop iconography, and her wit is chic and topical.”37

FS: If we think about art criticism and its often misguided disdain for a large swath of the potential viewing public, this can be telling. Marisol’s success in the mainstream was greater at that time and she may have been written off because of that. The 1960s art world was small and insular, and Marisol in 1962 was anything but. Did that affect her reception in the latter part of the 1960s and 1970s? I’d think so! On top of being a star, being a woman and being a woman with a hyphenated past certainly may not have enhanced her standing among those in the New York–centric art world.

JB: That’s such a good point—this idea that if something is “popular,” it is somehow less serious. It’s as if Marisol’s early success was used against her. I’m also interested in the role of gender in her early reception. For instance, her second show at the Stable Gallery, in February and March of 1964, featured the debut of her dry, witty assemblages John Wayne, The Family, and The Dinner Date (all 1963). When one sees these works alongside Warhol’s Silver Elvis, Campbell’s Soup, and Jackie paintings, her connection to Pop is clear. The pictorial irony in her art, revered in the work of other Pop artists, was dismissed as flippant by critics. There was this sense that she was just a girl who liked parties, and over time her work became marginalized, existing merely as a footnote to the movement she inspired and shaped. For me, Marisol is undeniably a Pop artist. The problem is that Pop, as a concept and definition, written about by Lippard and others, was and, I would argue, still is a term reserved for a small circle of white men.

FS: Efforts to address these issues have gone some way to changing perceptions, and this exhibition will further the conversation for the better. I am so curious to see Warhol in her context, and to see Marisol in Miami, a place with such a deep relationship to her Venezuelan heritage, but also a place where her particular handmade brand of Pop will be deeply engaging. And I am excited to see the multivalent nature of her work and its relationship to pre-Columbian and folk art, in addition to Cubism and Dadaism.

JB: I think another revelation in the exhibition will be the films. The summer of 1963 was when Warhol first attempted filmmaking. He made four films that summer focused on Marisol, John Giorno, and Wynn Chamberlain. But Warhol continues to film Marisol throughout 1963 and 1964: in her studio, at her second Stable Gallery show, and sitting for a screen test in his Silver Factory. These films will be shown alongside new juxtapositions of both artists’ work for the first time. It was, in fact, the 1963 film Robert Indiana, etc., with Marisol, Giorno, and Chamberlain, among others, that sparked the first idea for this exhibition. It’s a film that, for me, shows a more intimate, personal side of Warhol. What works are you most excited to see together, in person, for the first time?

FS: In Miami, I don’t think Warhol can overshadow in the way he might in New York City. The show presents a snapshot of two very cool, creative kids—one born in Paris and one born in Pittsburgh—trying to figure out how to make it in the big city, the world, and that story is universal and never gets old. The films also give a dynamic reference point to that earlier moment, which will further impress the historical nature and importance of this exhibition. That history will also play out in the narratives drawn in the subject matter of the two artists: political figures like the Kennedys; art historical figures like Henry Geldzahler, the first curator of contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the gallerist and connector Sidney Janis; art collectors like Ethel Scull; John Wayne and celebrities of popular culture like Jackie, Liz, and Elvis. There has not been a substantial viewing of either Marisol or Warhol here, so we are introducing many people to both of them for the first time. I personally might be most excited to see The Party, Marisol’s tour de force from 1965–66.

JB: The Party was such a hard loan to secure and will certainly be the most gratifying to see installed. There are also two Marisol works in the permanent collection at the Pérez that will be included in this exhibition: From France (1960) and Study for a Portrait of Sydney Janis (1969), which were great discoveries. Jorge Pérez’s loan, From France, is one of Marisol’s earliest assemblages and also points to her roots in Paris and is, as I read the work, a portrait of her parents. It’s a very significant work to include.

FS: For Jorge, the chance to acquire an important work by Marisol was paramount as part of the expansion of collection and its focal point on artists of Latin America. The acquisition at auction just a few years ago came after deep research with his curatorial team. Previously, From France had been in the same collection from 1964 until 2018. This early Marisol work has such a rich history, having been selected for the Museum of Modern Art’s The Art of Assemblage exhibition in 1961.

JB: My hope is that this exhibition will contribute to the revision of the history of Pop and recover Marisol’s artistic vision and singular voice. From my perspective, Warhol followed Marisol’s lead and even took notes on her reticent style with the media. It’s important to me that her name appears first in the title of the show and throughout the entire narrative—she is the real trailblazer!

FS: I am right there with you on that!

D.S. Kinsel and Quaishawn Whitlock

About the Collection Close-Ups Series

Collection Close-Ups is a free video series that invites artists and community members to engage in dialogue about the contemporary relevance of objects in The Andy Warhol Museum’s collection. To watch more Collection Close-Ups videos, visit the archives.

About the Learning and Public Engagement Team

The Warhol’s Learning and Public Engagement team strives to engage audiences from different walks of life with relevant, accessible opportunities for learning, creative expression, skill-building, and connection. Whether at the museum, in the community, or online, our goal is to leave our audiences feeling inspired, empowered, and equipped with the skills they need to thrive in a changing world. To learn more, visit warhol.org.

Cassandra Jenkins

Cassandra Jenkins performs “Michelangelo” and “Crosshairs” in this special “at home” Silver Studio Session.

Credits

Ben Harrison, Curator of Performing Arts and Special Projects

Production by Foothold Studios

About Silver Studio Sessions

Silver Studio Sessions is a video series that offers stripped-down sets from our Sound Series artists in spaces inspired by Andy Warhol. To watch more Silver Studio Sessions, visit our YouTube channel.

About Sound Series

Sound Series is an ongoing concert series featuring internationally touring contemporary artists and bands from around the world. To learn more about the Sound Series, visit warhol.org.

Warhol Without Walls

A global digital initiative created by The Andy Warhol Museum to expand public discourse around art and its role in a changing world, Warhol Without Walls signals a more boundless embrace of experimentation in the original content that the institution produces.

Just American

Image Gallery

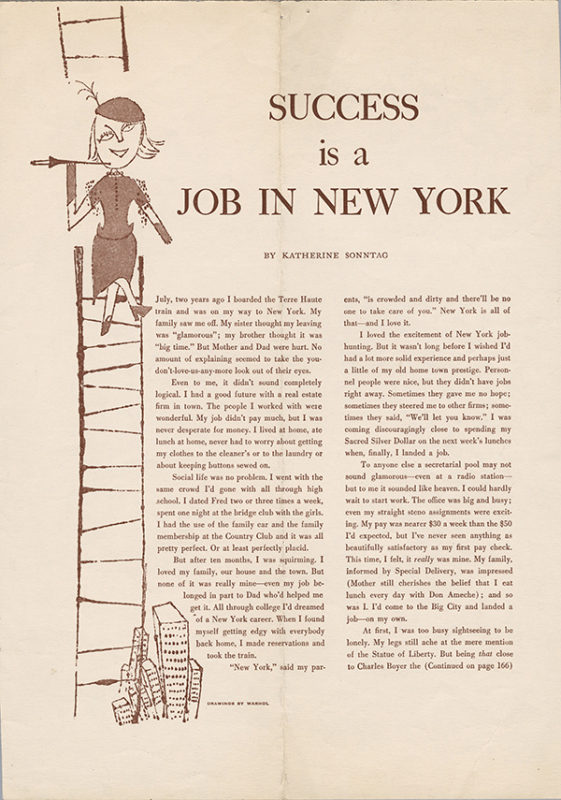

Warhol’s first assignment as a professional artist in New York consisted of illustrations for a group of articles in Glamour magazine published under the heading “What Is Success?” The articles, by various writers, provided different answers to the question, and one of them was titled “Success Is a Job in New York.” The text was written by a young woman who had abandoned a “perfectly placid” life and took a train to the Big Apple with big aspirations and a thirst for adventure.38 Her story aligned with that of Warhol, who, upon leaving Pittsburgh, dropped the final a in his surname and was on the way to becoming a leading commercial illustrator.

Like Warhol or the journalist who defined her idea of success in the pages of Glamour, the contemporary artists represented in Fantasy America, some native New Yorkers and others transplants, have all pursued careers in the city. These artists—Nona Faustine, Kambui Olujimi, Pacifico Silano, Naama Tsabar, and Chloe Wise—address contemporary culture in the United States three decades after Warhol. All are, like Warhol, multidisciplinary artists who produce work that blurs the boundaries between form and concept, offering a complex picture of contemporary life. Faustine confronts modern injustices through photographs centered on public monuments and buildings related to hidden African American histories. Olujimi addresses nationhood and the colonization of bodies, land, time, and space, surfacing buried political pasts. Silano rearranges tear sheets from vintage gay magazines to explore love and loss in queer culture. Tsabar uses her body and sound compositions to perform outside the boundaries of gender norms with an array of female and gender-nonconforming collaborators. Wise deconstructs advertising and audience through staged narratives in painting and film to reveal tenuously manufactured social contracts and constructs. All are, in different ways, reflecting on their own custom-made “dream Americas” while providing incisive commentary on the real one that we all live in.

* * *

In the 1950s Warhol achieved success as an adman, becoming one of the industry’s most in-demand commercial artists. By 1961, however, he would develop a new artistic style and establish himself as a Pop artist occupying the center of attention among his contemporaries and patrons. As Pop art spread across the country, Warhol began silk-screening portraits of Jackie Kennedy, Brillo Box sculptures, and the 13 Most Wanted Men, a mural commission for the 1964 New York World’s Fair that was censored because of the (desirable) criminals depicted. That year Warhol went to Paris, where he had his first European solo show and debuted the Death and Disaster paintings, which featured gory images taken from mass media. His original working title for the show, Death in America, went unused, but the artworks were understood immediately.39

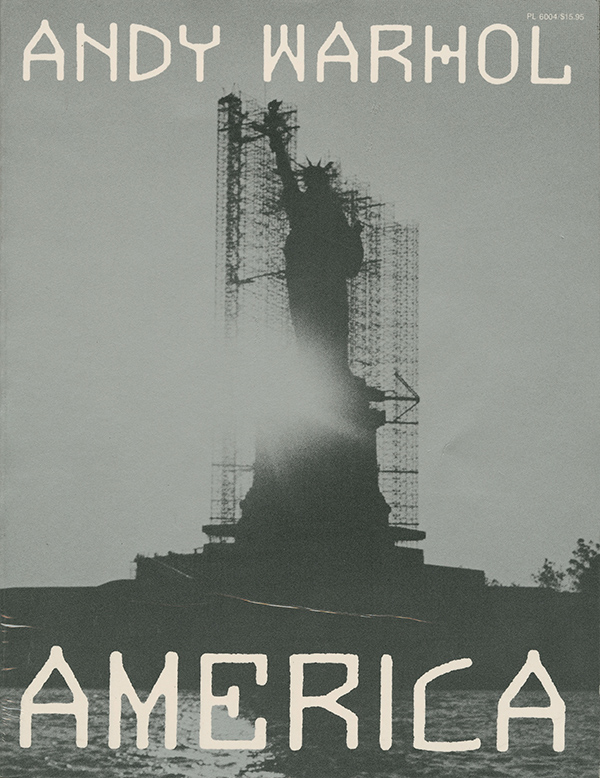

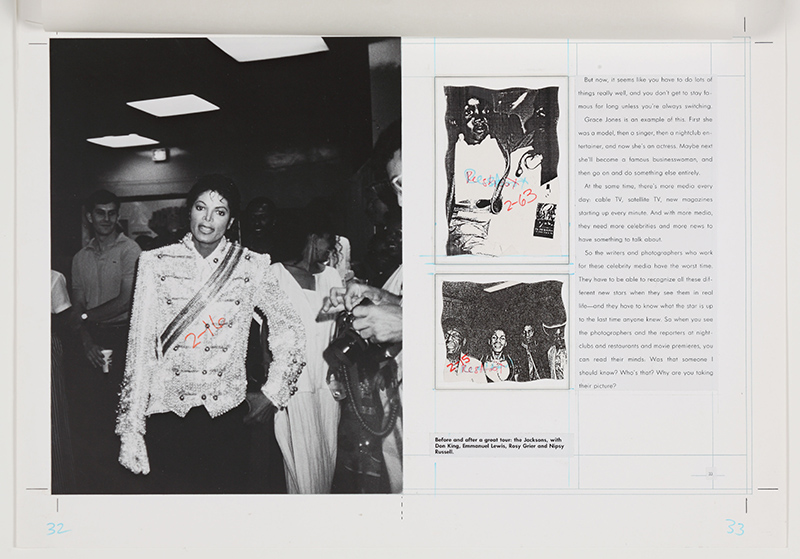

By the 1980s Warhol was one of the most recognized living artists and cultural icons. His hopscotching around creative disciplines allowed him to make films, publish Interview magazine, receive lucrative commissions, pursue a late modeling career, and produce Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes for the newly launched music channel MTV. Warhol also created many books during his lifetime. Early in his career he illustrated self-published books, including 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy (1954) and Wild Raspberries (1959), a nonsensical cookbook with outrageous recipes. Later he acquired book deals for mainstream publications, including The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again) (1975); the celebrity-studded photo book Exposures (1979); and POPism: The Warhol Sixties (1980), a memoir. All were written with colleagues and assistants, but Warhol, much as he did with his artworks, marketed them as his own. His final book, America, published in 1985, captured the essence of its era. (The Andy Warhol Diaries would be published posthumously, in 1989.)

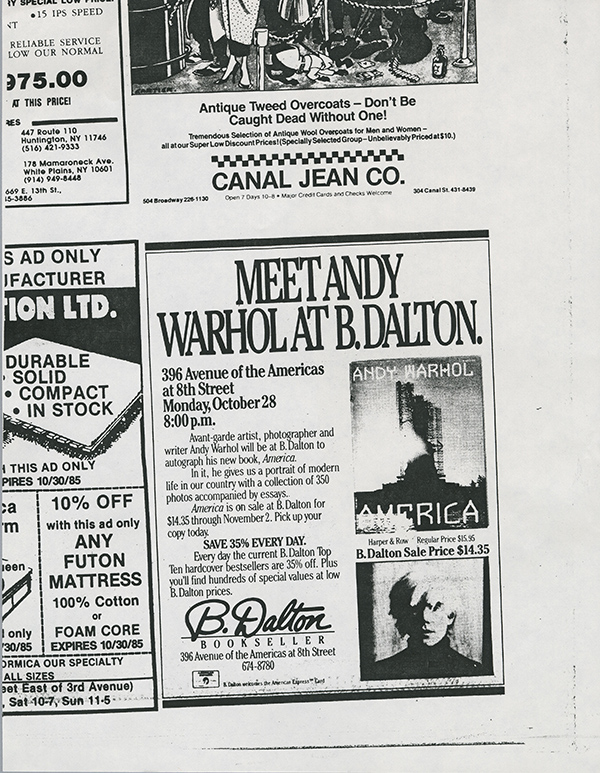

Image Gallery

America was unpretentious. “It’ll be a book of photographs with just a little text—maybe just captions,” the artist mentioned in his diary.40 An advertisement for the finished book praises the “Avant-Garde artist, photographer, and writer” for showing readers, “a portrait of modern life in our country.”41 Critics were skeptical of the authenticity of Warhol’s voice, however, as well as his dedication to the project.42 Like Frankenstein’s monster, America was in fact stitched together and given life from existing materials: previously published quotes and hundreds of photographs, both new and old. It was designed to resemble a hybrid of yearbook, zine, and scrapbook.

Two years earlier Craig Nelson, an editor at the publishing house Harper & Row, had corresponded with Warhol to propose America, title as well as content. Historically Warhol had always been open to ideas for his projects.43 Nelson would immediately come on board as the editor of America and wear many hats during its completion and promotion. (He had also secured a deal with the artist Laurie Anderson to publish a book titled United States with the very same team.)44 For the book’s text Nelson gathered existing Warholian passages and drafted his own contributions, which Warhol “fiddled with” later. Supplying photographs for the book become an additional task because, “an awful lot of the pictures turned out to be not that interesting in the archives,” Nelson recalled, and “a lot of my work was actually dragging Andy out to do things to take new pictures for the book to give him a fresher, more interesting look.”45 This ambrosia salad of a project also included photographs taken by Nelson, Christopher Makos, Paige Powell, a paparazzo, and a socialite. Finally the book’s designer had “free rein” in creating the layout, which took her one weekend to complete.46 In the end America would become part of Warhol’s creative output but remain relatively obscure after his death in 1987.

* * *

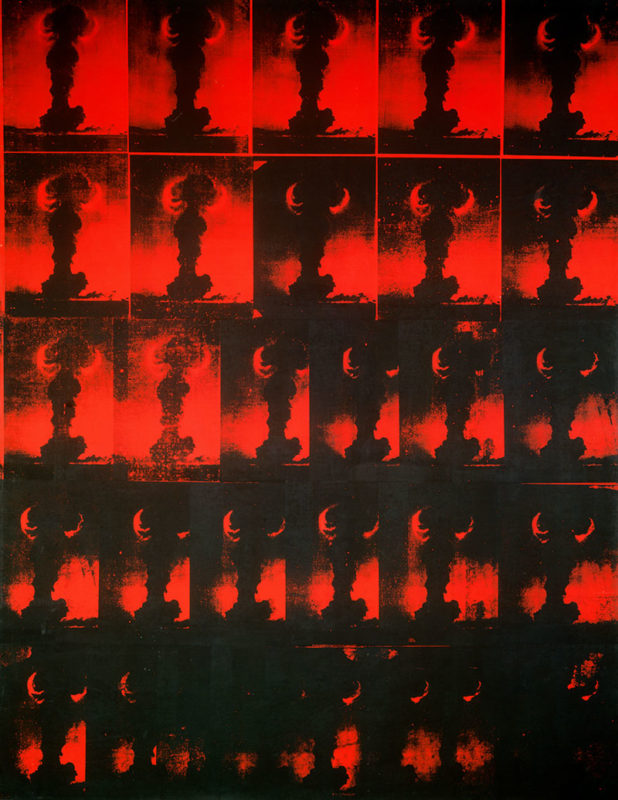

Whether appropriating images or taking original photographs, Warhol acted as a passive observer who amplified the (in)significance of his everyday surroundings. His Pop canvases of the 1960s re-presented press images of current events—including the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, attacks by police on civil rights protestors, and car wrecks and suicides—through the eyes of an emerging queer artist. These images might have attracted him for various reasons, but he understood their power to rattle viewers, even himself. For example, on August 6, 1945, Warhol’s seventeenth birthday, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, killing vast numbers of people and leading to Japan’s surrender.47 The unforgettable image of the mushroom cloud produced would perhaps haunt the artist, as it was depicted by him once, two decades later, repeatedly silk-screened in black ink on a red canvas.

The chapters in America divide the photographs into sections, most titled after popular magazines. For example, “People” is filled with photos of (still) well-known celebrities, including Dolly Parton, Mick Jagger, and Grace Jones. The chapter “Physique Pictorial” features wrestlers, beauty queens, and male strippers. Other chapters include “Life,” “Vogue,” and “Natural History.” The hardiest chapter, “National Geographic,” includes photos from travels across the country, from New York to Los Angeles. The images appear as clichéd snapshots, similar to those of a tourist, of places like the White House, the Twin Towers, and the Paramount Pictures studios in California (the latter likely a tribute to Warhol’s then boyfriend, Jon Gould, who was an executive at Paramount). Images in the book echo the American subject matter of other Warhol works, including the Statue of Liberty, the Washington Monument, and the Empire State Building, the star of the eight-hour film Empire (1964), which consists of a stationary shot of the building from dusk until dawn.

Passages throughout the book take on beauty, consumerism, and fame, just as one would expect. Yet new subjects are also covered—including poverty, immigration, and technology—all with an opinionated tone. For example: “Every year there’d be a new scientific discovery or a new invention, and everyone would think the future was going to be even more wonderful than ever. . . . Now it seems like nobody has big hopes for the future. We all seem to think that it’s going to be just like it is now, only worse.”48 Or: “This country is so rich. And I think I see more homeless people on the street every month. How can we let this keep happening?”49 Regardless of Nelson’s uncredited contributions, like those of others before him, the entire text possesses Warhol’s relevant opinions and timelessness, ringing true even thirty-five years later.

* * *

America had a hectic promotional tour with scheduled appearances by the artist. With the recent Olympic Games hosted in Los Angeles, a renovation of the Statue of Liberty, and the humanitarian hit ballad “We Are the World,” American culture was on everyone’s radar. From October through December 1985 Warhol traveled to Washington, DC, Detroit, Boston, Chicago, and Dallas. At a signing at the Rizzoli bookstore in New York, a young woman with a copy of America, meant to be autographed, quickly yanked off Warhol’s platinum wig and tossed it from the store’s balcony down to an accomplice, who fled. Warhol quickly pulled the hood from his jacket over his head. Humiliated but committed to the project, he stayed and continued to sign copies of the book. He was left shaken and distressed over the incident.50 “It was shocking. It hurt. Physically. And it hurt that nobody had warned me. . . . So that’s that and now I never have to talk about it again,” he later confided to his diary.51

Image Gallery

Photocopy of an ad for a book signing at B. Dalton, New York, October 28, 1985. The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. TC451.52.8

Warhol was clearly upset. During the preparation and completion of America, his private life was complicated. In February 1984 Jon Gould, his live-in boyfriend, was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and diagnosed with AIDS. Warhol, who may not have been completely informed about Gould’s health, had feared catching the disease based on what he knew about it.52 The artist had been shot in 1968 by a would-be assassin and continued to have various ailments throughout the rest of his life. Known for avoiding medical doctors, he tended to his health and well-being through personal trainers, magic crystals, and “popping into church.”53

By 1985 Gould, a closeted gay man, had distanced himself from Warhol and moved back to Los Angeles. That summer AIDS gained mainstream visibility when the actor Rock Hudson announced that he had contracted the disease; he died of complications of it in October. By then Warhol was well aware of the epidemic given what he had witnessed. Gould passed away on September 18, 1986, at the age of thirty-three, blind and weighing just seventy pounds. Warhol left this out of his diary, noting a few days later, “And the Diary can write itself on the other news from L.A., which I don’t want to talk about.”54 In America, Gould appears in photos, uncredited, at Warhol’s recreational compound in Montauk, on Long Island, where the two had spent happier times together.

* * *

Death was in the air. Parallel to the America project, Warhol was commissioned in 1984 by the art dealer Alexander Iolas to create a Last Supper series consisting of more than one hundred works, all depicting aspects of Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic mural, painted from 1495 to 1498 in the refectory of Milan’s Santa Maria delle Grazie convent. In January 1987 twenty-two of Warhol’s Last Supper works were exhibited in a former monastery directly across the street from the original. The biblical narrative, one that he had known since childhood, features Jesus Christ at a final gathering before his crucifixion.55 The scene foreshadows the ascension of Christ, yet Warhol’s version seems to adumbrate his own unexpected demise. The artist died in New York on February 22, 1987, due to complications following surgery to remove his gall bladder.56

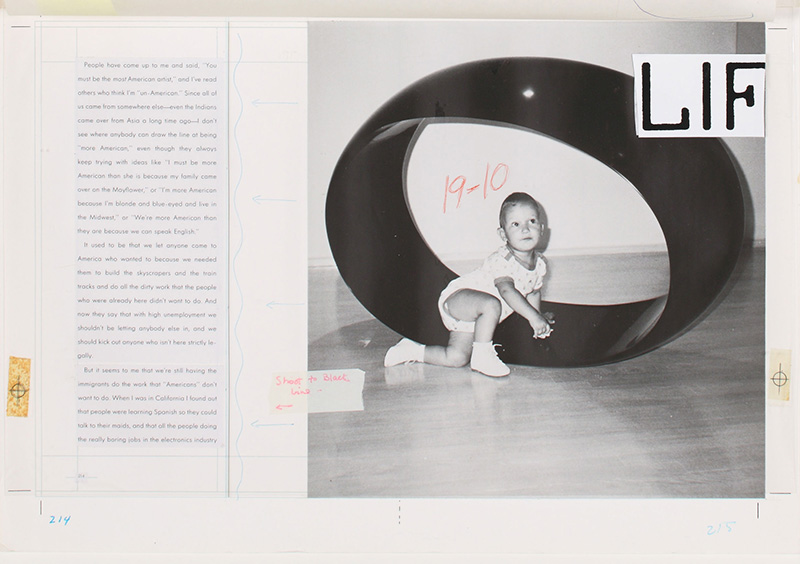

The final chapter of America is titled “Life,” and the text and accompanying images conclude with hope for the future. According to one critic, “As a book of photographs, America is entirely successful and in keeping with Warhol’s output as a painter and filmmaker. Potent one day, disposable the next, Warhol’s camera eye delivers a cynical but deadly accurate picture of our times.”57 The photos in “Life,” which depict toddlers and children, do not appear to partake of this cynicism. In strollers, on a parental lap, or playing together, the children are often accompanied by artworks. One child poses beneath a large circular sculpture. Another wears a Keith Haring T-shirt featuring a cartoonish illustration of a crawling child with dashed vertical lines around the body. This image is known as the Radiant Baby, and Haring stated, “The reason that the ‘baby’ has become my logo or signature is that it is the purest and most positive experience of human existence.”58

Image Gallery

The pairing of the child and Haring’s baby image emphasizes the importance of life but also of artists. Warhol’s America includes images of young, emerging artists of the moment—including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Francesco Clemente, Eric Fischl, Jedd Garet, Keith Haring, Victor Hugo, Kenny Scharf, Julian Schnabel, and John Sex—many of whom he befriended and even collaborated with.59 In September 1983 the Black graffiti artist Michael Stewart died while in the custody of the New York City Transit Police. Warhol noted that Haring was upset, “ranting and raving about this black graffiti artist that’s in the papers now because the police killed him—Michael Stewart. And Keith said that he’s been arrested by the police four times, but that because he looks normal they just sort of call him a fairy and let him go. But this kid that was killed, he had the Jean Michel look—dreadlocks.”60 Many artists at the time made works that protested the unjust killing, including Haring in 1985. Warhol understood what it means to be young, creative, and different in America. He had also witnessed the destruction of so many creatively chaotic peers and followers, and yet he survived to achieve his own version of the American Dream. (His parents immigrated to this country via Ellis Island with dreams of a better life.)61 Warhol concludes the book with a hopeful message: “We all came here from somewhere else, and everybody who wants to live in America and obey the law should be able to come too, and there’s no such thing as being more or less American, just American.”62

A consideration of Warhol’s final decade, in both his personal and professional lives, reveals a contemplative older queer man pondering life in the United States. Many of the social and political issues of the day might not have affected him directly, but he certainly observed and reflected on them through his artistic production, including America. His admiration for his own generation of artists as well as those that followed was well known and continued through his legacy, a foundation established after his death.63 The artists featured in Fantasy America are representatives of a new generation who continue to question life and explore their own experiences and surroundings. Whether responding to social and political concerns or pop culture, Faustine, Olujimi, Silano, Tsabar, and Wise depict life and death, resilience and vulnerability, isolation and community, joy and sadness, fame and failure, dreadfulness and beauty, as well as (in)justice, gender, sexuality, and otherness to weave a fantasy America that is not more or less American but just American.

Acetate Collage

About the Making It Series

The Warhol’s Making It videos are designed to spark creativity and engagement at home. Artist educators demonstrate short, accessible hands-on activities inspired by Warhol’s life, art, and legacy. Designed for makers of all ages and skill levels, these award-winning activities use simple materials commonly available around the house and encourage playful experimentation. To watch more Making It videos, visit the archives.

About the Learning and Public Engagement Team

The Warhol’s Learning and Public Engagement team strives to engage audiences from different walks of life with relevant, accessible opportunities for learning, creative expression, skill-building, and connection. Whether at the museum, in the community, or online, our goal is to leave our audiences feeling inspired, empowered, and equipped with the skills they need to thrive in a changing world. To learn more, visit warhol.org.

Vieux Farka Touré

Vieux Farka Touré performs “Ali” and “All The Same” in this special “at home” Silver Studio Session.

Credits

Ben Harrison, Curator of Performing Arts and Special Projects

Production by Foothold Studios

About Silver Studio Sessions

Silver Studio Sessions is a video series that offers stripped-down sets from our Sound Series artists in spaces inspired by Andy Warhol. To watch more Silver Studio Sessions, visit our YouTube channel.

About Sound Series

Sound Series is an ongoing concert series featuring internationally touring contemporary artists and bands from around the world. To learn more about the Sound Series, visit warhol.org.

Warhol Without Walls

A global digital initiative created by The Andy Warhol Museum to expand public discourse around art and its role in a changing world, Warhol Without Walls signals a more boundless embrace of experimentation in the original content that the institution produces.

Alan Pelaez Lopez and Jessica Lanay Moore Discuss ‘Fantasy America’

Sarah Huny Young on Basquiat, the Black Body, and Truth-Telling in Art

About the Collection Close-Ups Series

Collection Close-Ups is a free video series that invites artists and community members to engage in dialogue about the contemporary relevance of objects in The Andy Warhol Museum’s collection. To watch more Collection Close-Ups videos, visit the archives.

About the Learning and Public Engagement Team

The Warhol’s Learning and Public Engagement team strives to engage audiences from different walks of life with relevant, accessible opportunities for learning, creative expression, skill-building, and connection. Whether at the museum, in the community, or online, our goal is to leave our audiences feeling inspired, empowered, and equipped with the skills they need to thrive in a changing world. To learn more, visit warhol.org.